Photos of the Side of Havana That Most People Never See

February 20, 2019“When I was younger I felt like I could communicate better in photographs than I could in words,” Rose Marie Cromwell says. “It was the the first time I really had a lot of self-confidence in what I was expressing.”

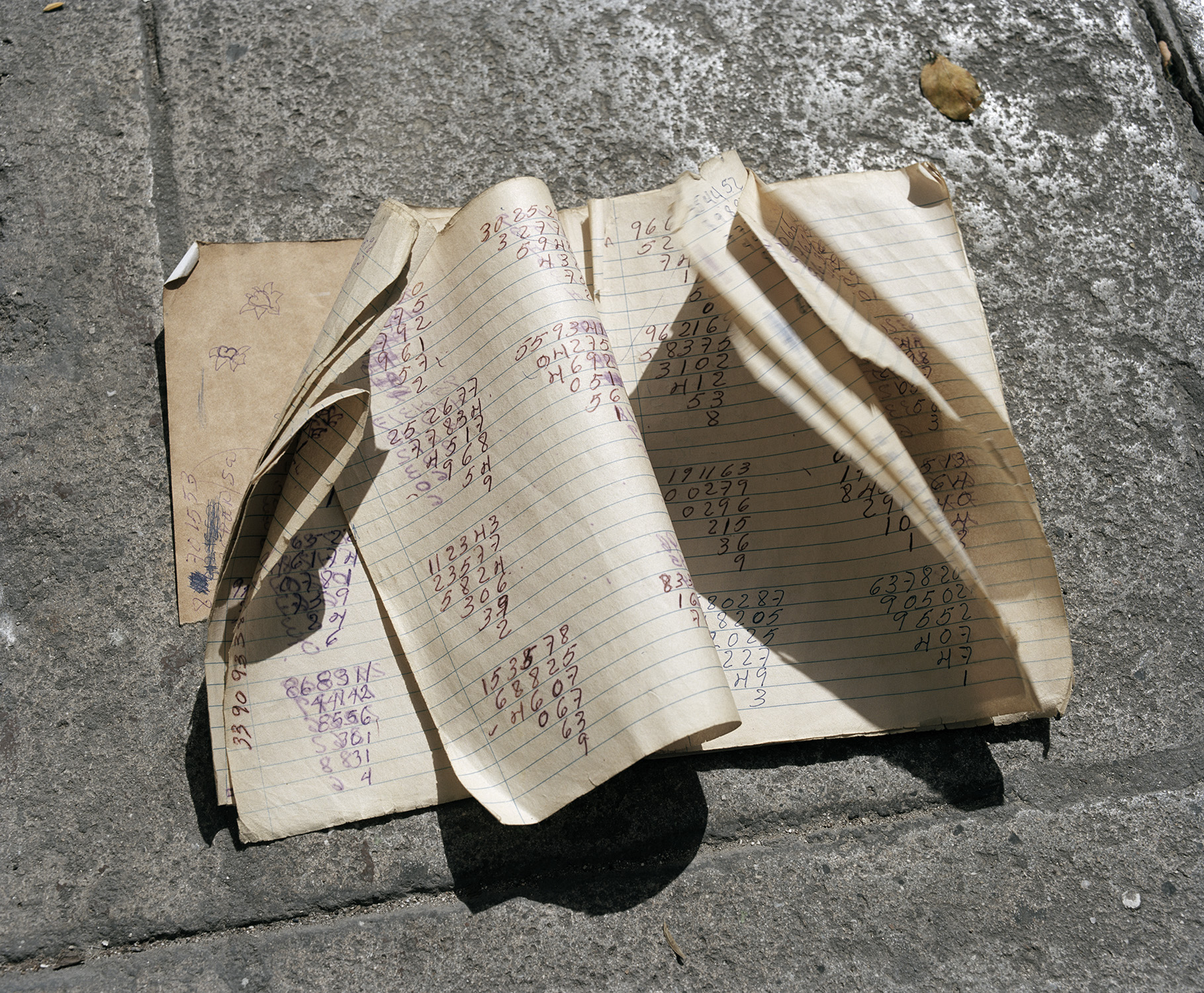

Her most recent book of photography, the Light Work Photobook Award-winning El Libro Supremo de la Suerte, speaks volumes, giving readers an intimate look at life in Havana. The title translates to “The Supreme Book of Luck,” and it's thematically inspired by a booklet rooted in Cuban culture explaining La Charada, a system of symbols that attributes significance to numbers 1 to 100 and is also used to play numbers in an underground lottery. Depending on one’s life events or objects encountered, you might choose to play a different number. A clock is notated by number 85, for example, whereas “old prostitute” becomes number 98.

With her book, Cromwell has both found and created images that evoke the randomness of the lottery itself and in doing so creates a vibrant portrait of Havana. By incorporating objects in this specific expository context—like in La Charada or in a photograph—she give them meaning they may have not had before. Subjects are no longer just a bright yellow fan against a mauve backdrop, a collection of fruits under a white sheet, or a woman with bright red lipstick staring up at the sky. Instead, they now represent a collection of experiences and visuals that reflect whatever chaos or capriciousness we face.

This photography collection has also influenced all of Cromwell's work that's followed, by making her look at the world differently. “That experience and working on that project has informed all work afterwards. Even in photojournalism you can’t insert yourself so much, but you can find an act of performance in somebody’s gesture,” she says. “[You’re] paying attention more to how people move and communicate if you’re photographing a person." Cromwell says she is the most confident she ever has been. “I think the work I made for my book was essential for finding a photographic voice and asserting myself a little bit more as a photographer and listening to my intuition,” she says.

Cromwell is happiest when her images toe the line between conceptual and documentary work. She began working as a documentary photographer during a Fulbright fellowship in Panama in 2007, drawn to the country by its history of U.S. intervention, a growing consciousness of world trade, and a desire to chronicle the effects of globalization. “I think that there’s such high inequality in the world because we’re just consumers and everything, for example, that passes through the Panama Canal maybe is passing by communities that don’t have water,” she says.

Getting her MFA in art photography at Syracuse taught Cromwell theoretical frameworks for approaching photography in new ways, and she began thinking more conceptually. “I think there can be poetry and journalism, there definitely is,” she says. “It’s just something that’s innate.”

Cromwell hopes to tell stories about the effects of globalization by making global issues feel personal. She creates images that, in telling the close-up stories of individuals, also draw attention to larger economic and political systems at work. “How do you tell a story, like [how] somebody’s life is informed by globalization, and in what ways?” she asks. “How do we make it personal for other people to relate?”

Cromwell's ongoing series “King of Fish,” for example, tells the story of the son of a pastor and reformed drug dealer living in Panamanian public housing. In doing so she also tells the story of how a marginalized community is affected by the governing body meant to protect it. Her newest ongoing work, “IMAIM,” chronicles the portions of Miami not regularly covered by media or travel resources. She shows her audience that not everything is sparkling, sanitized clubs and Art Basel—there’s detritus and poverty and demolition, too.

“I can only hope that if people haven’t paid attention before maybe [the work] provokes something in them to think about a place in a different way,” she says. “I am really concerned about certain issues in the world and sometimes I feel the best thing to do is work towards expressing your feelings about those things.” And for Cromwell, the best way is and has always been through images.

Sign up for our newsletter to get the best of VICE delivered to your inbox daily.

Follow Elyssa Goodman on Instagram.