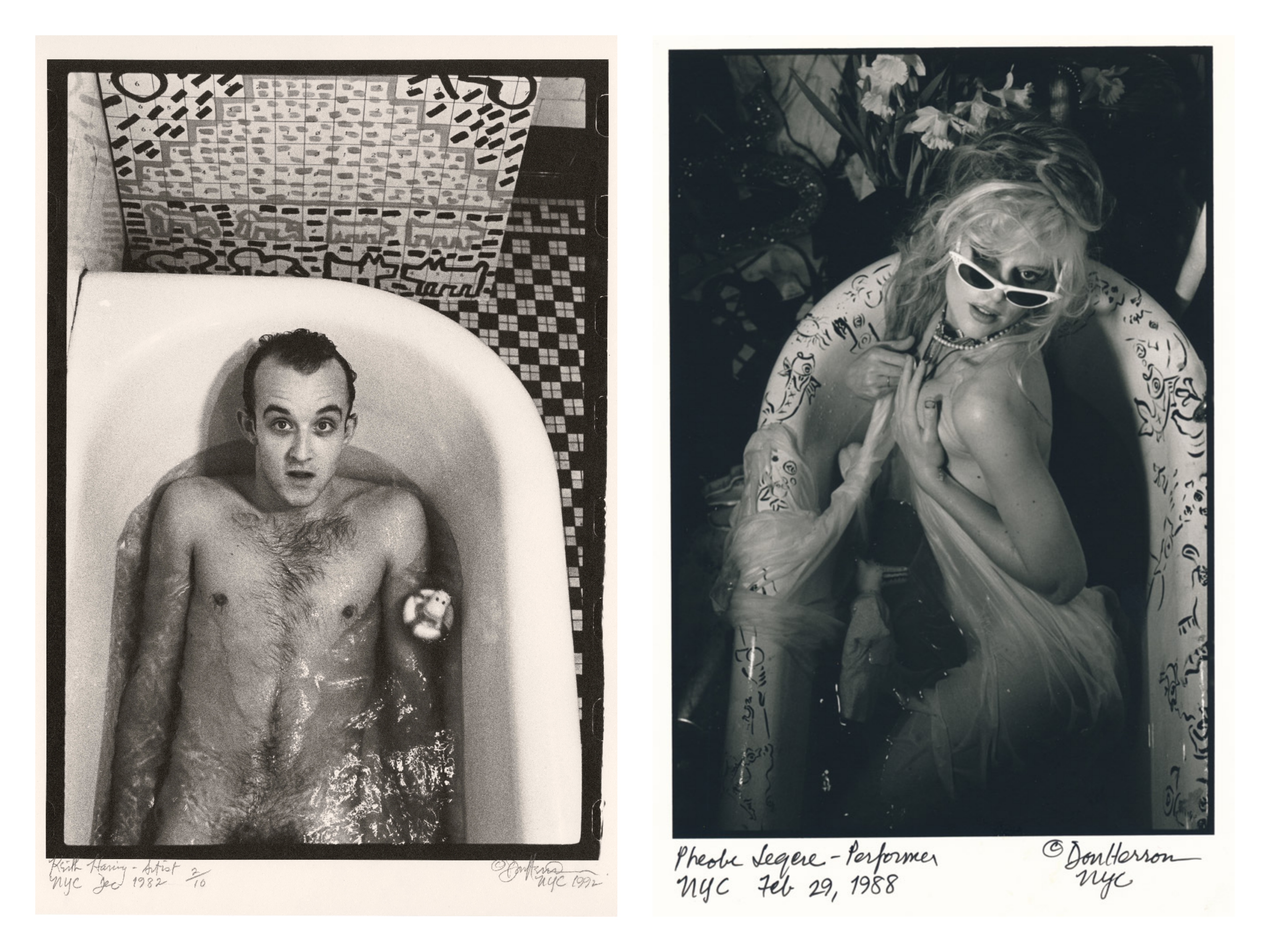

This Photographer Shot Portraits of His Famous Friends in the Tub

September 19, 2018 Off By Miss RosenWhen artist Don Herron moved to New York City from Texas in 1978, the fledgling East Village art scene was just beginning to take shape. Soho was the capital of downtown New York, but artists were starting to take up residence in the Lower East Side, where rent was affordable and young artists could find a tight-knit community of peers.

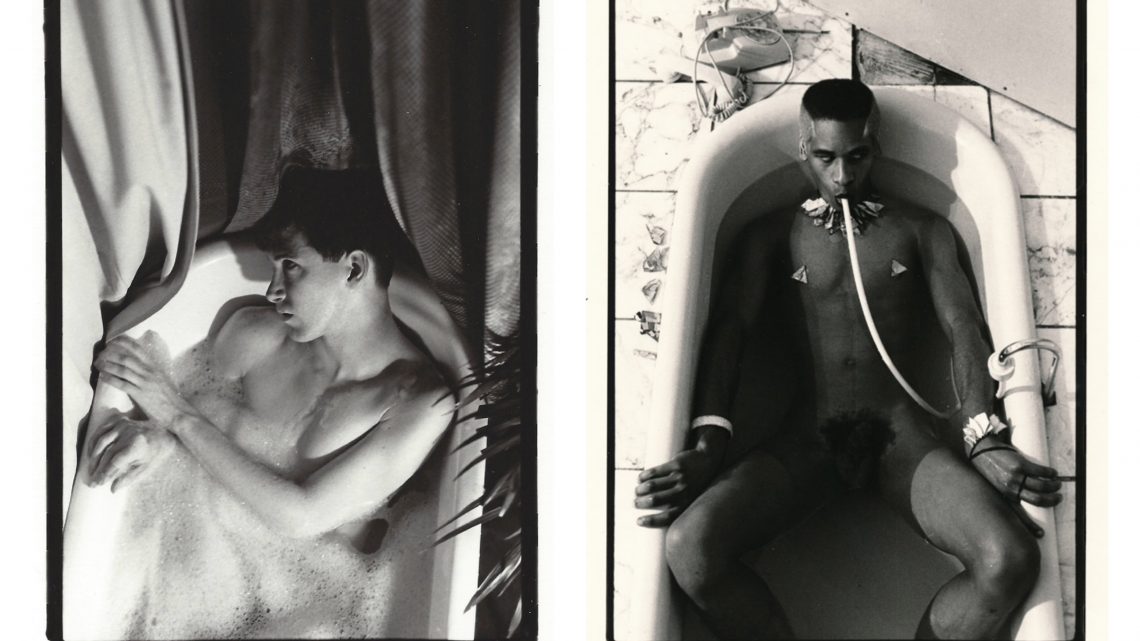

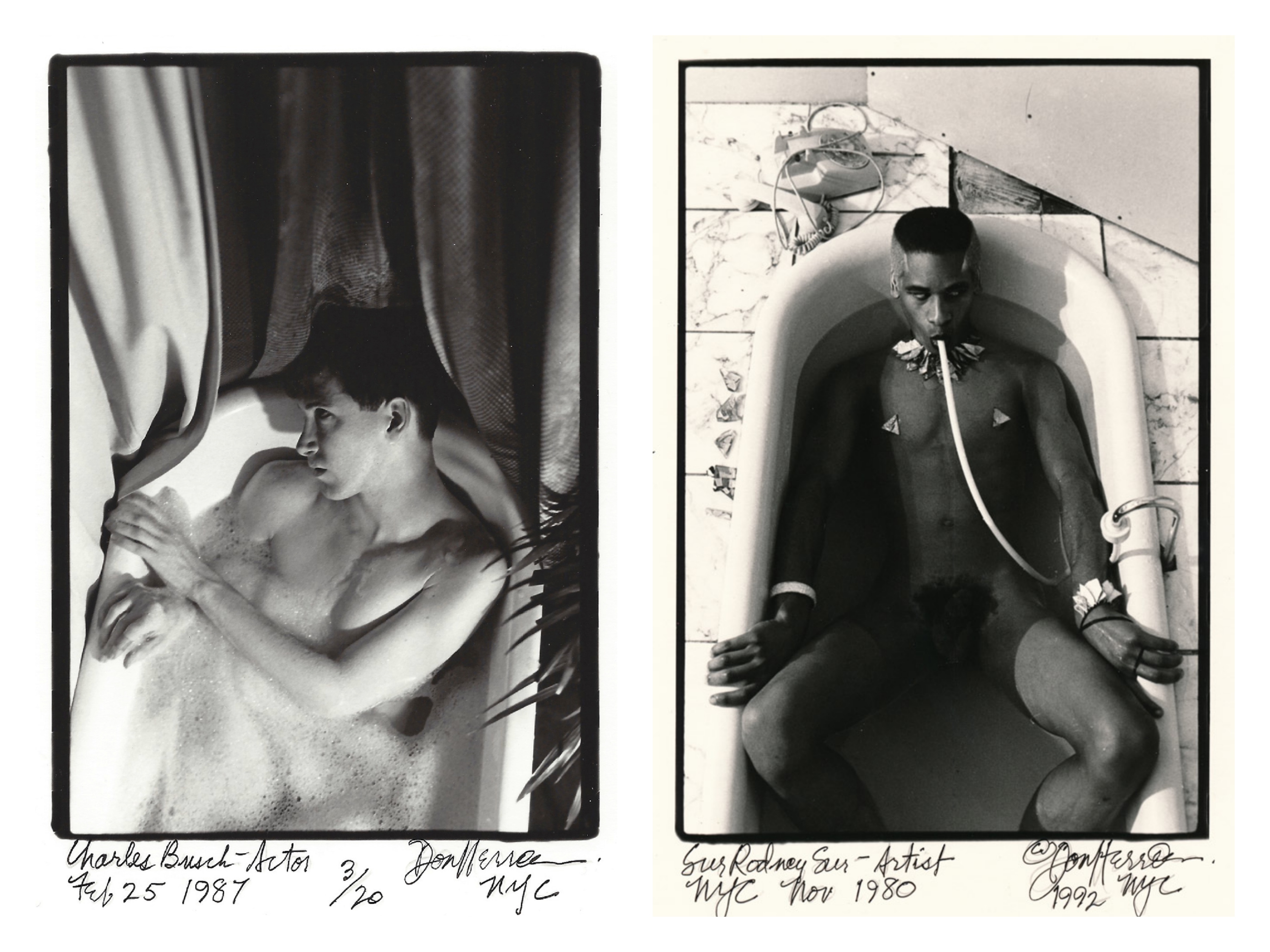

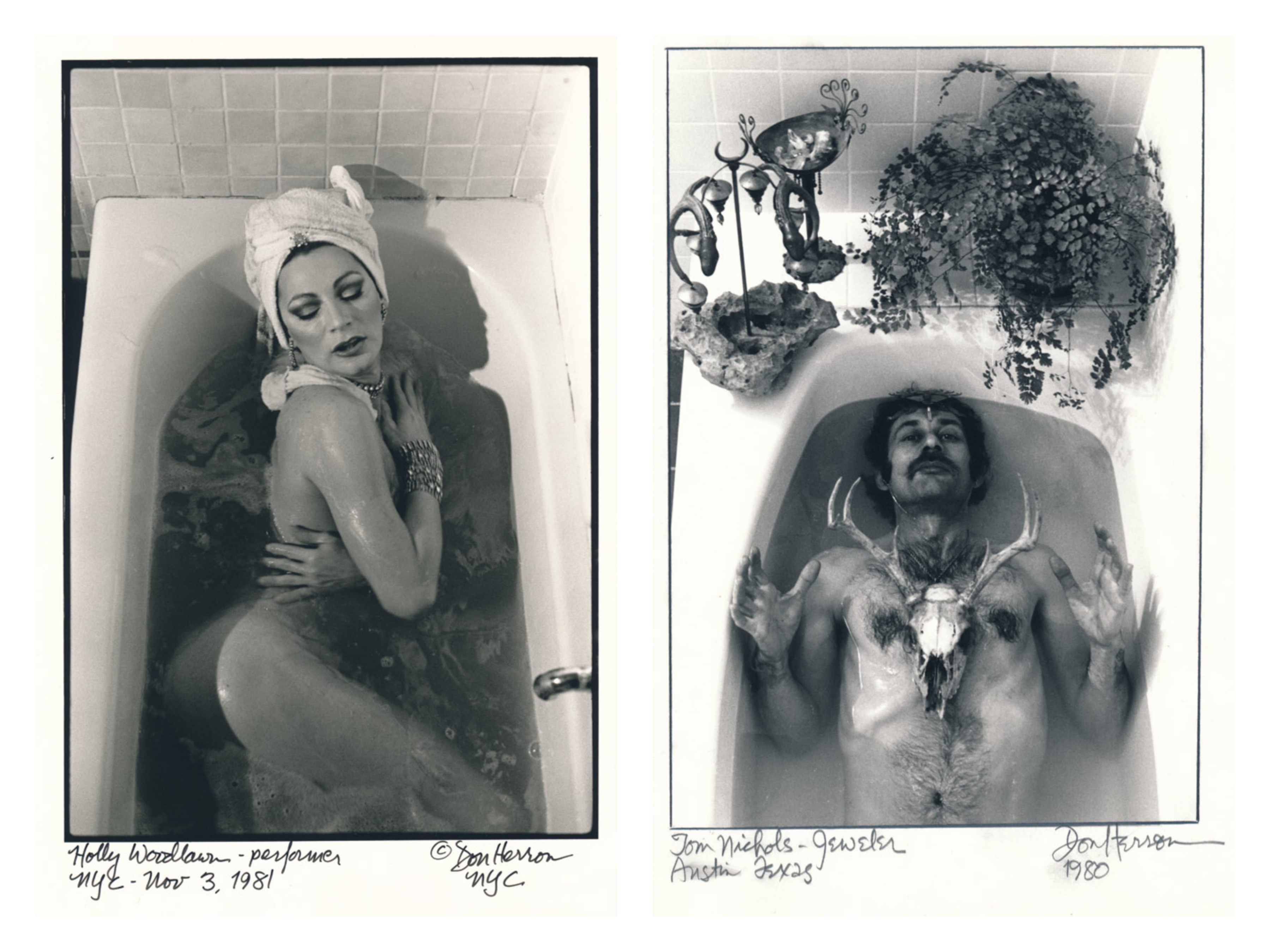

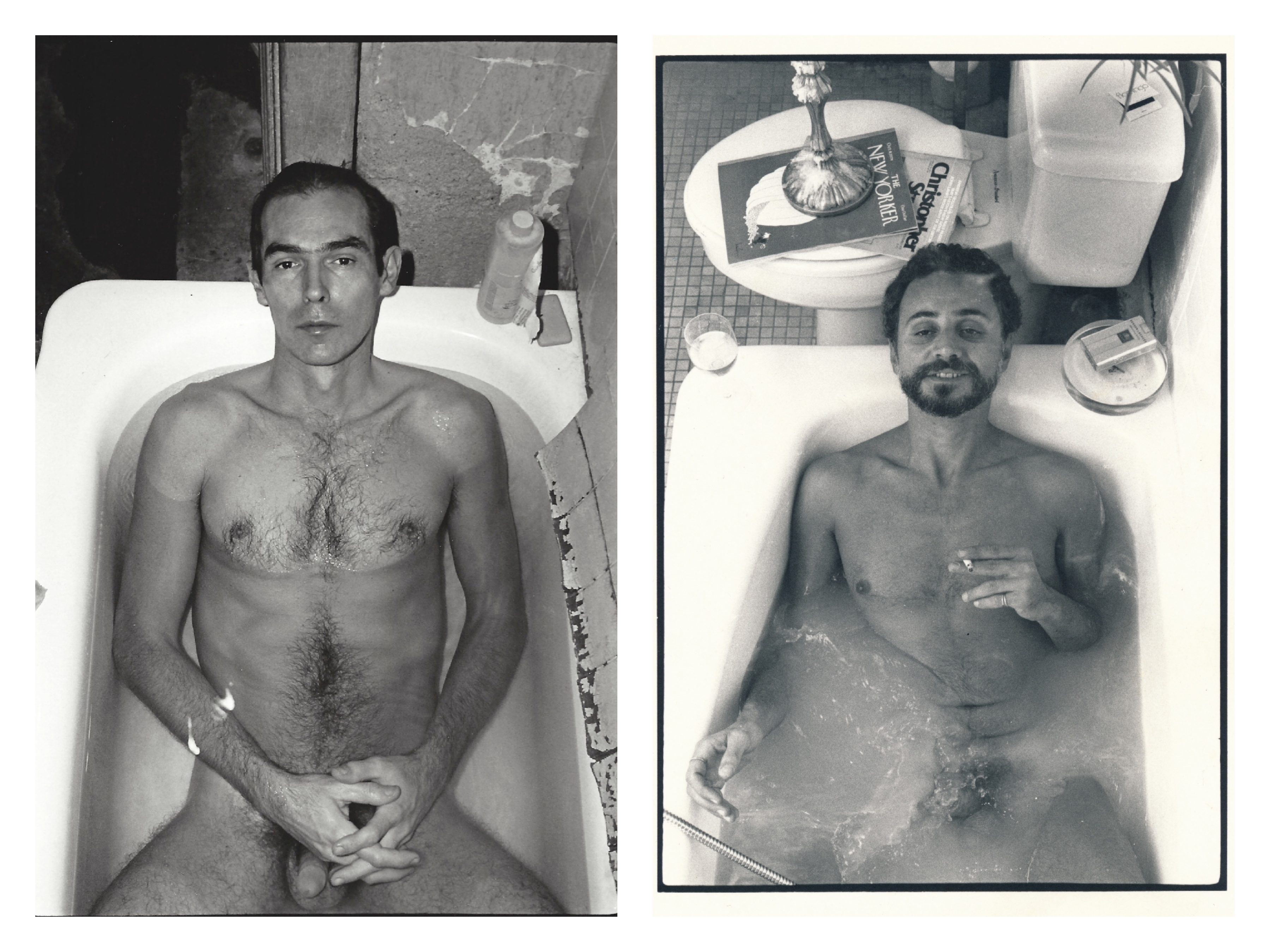

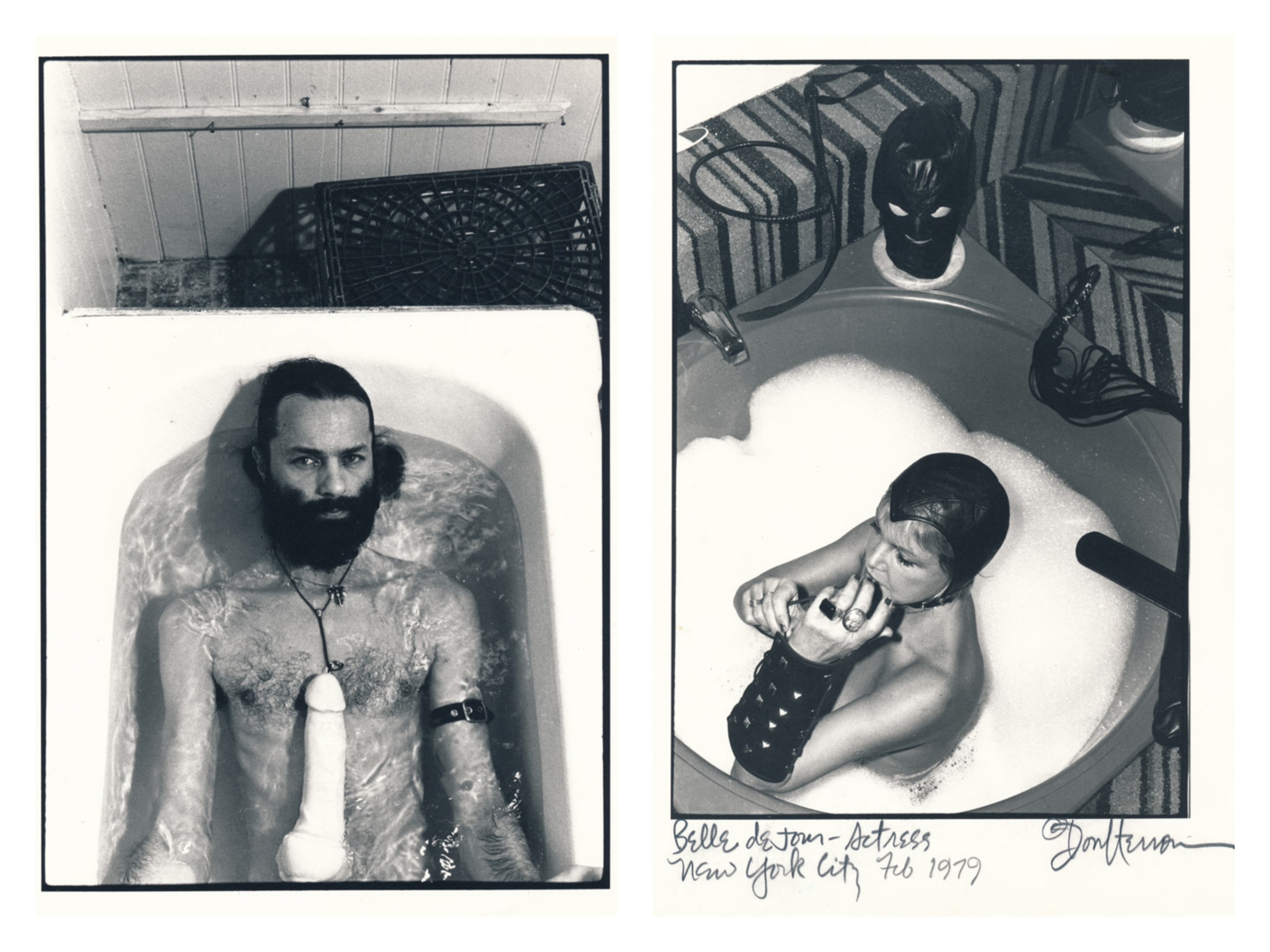

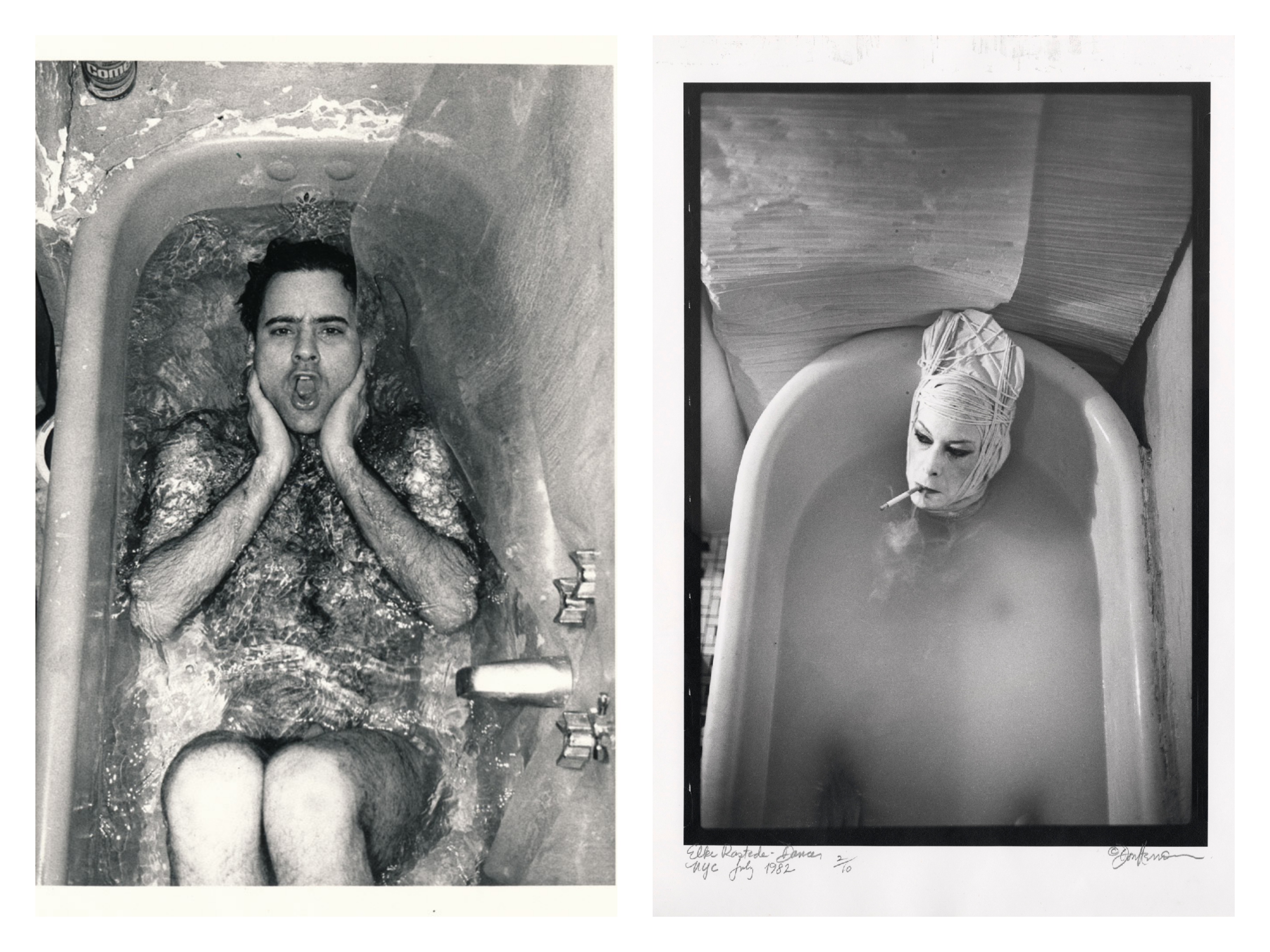

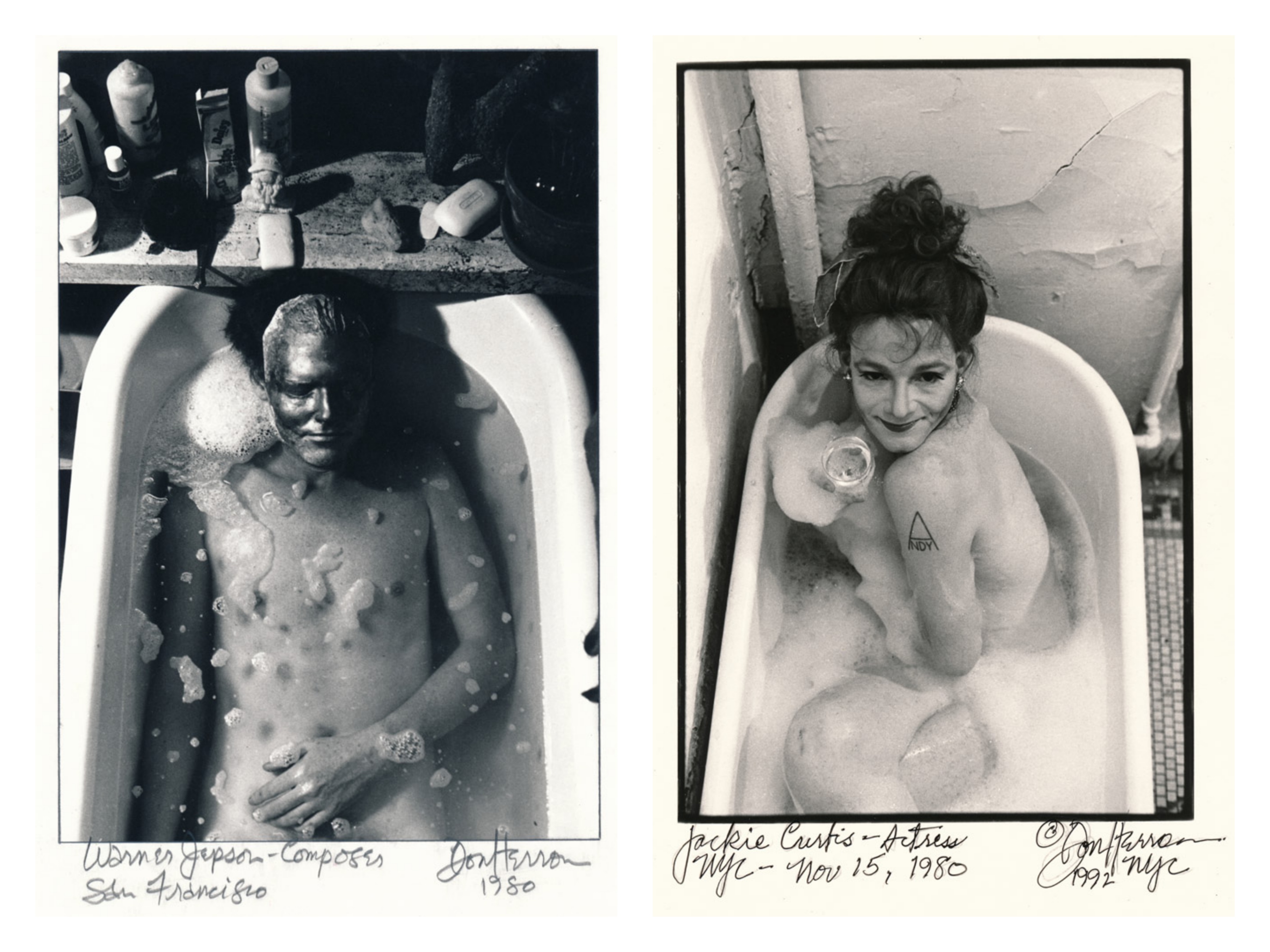

While getting to know New York's art luminaries, Herron conceived of a project he titled Tub Shots, wherein he would photograph downtown cult figures in their bathtubs. From 1978 to 1993, he photographed art stars like Robert Mapplethorpe, Keith Haring, Peter Hujar, and Annie Sprinkle, along with Warhol Superstars like Holly Woodlawn, and International Chrysis.

Some artists collaborated with Herron to stage a scene, while others opted for a bare bones approach; a few were exhibitionist, while others posed demurely. Each portrait offers a glimpse of the subject as they were rarely seen—in a space that is both private and sensual, vulnerable and daring.

Herron died in 2013, but a selection of his photographs are on view in Don Herron: Tub Shots at Daniel Cooney Fine Art in New York. VICE asked downtown icons Sur Rodney (Sur) and Charles Busch to share their memories of working with Herron and being part of the East Village art scene when the photos were made.

VICE: What was it like being part of the New York art scene in the 70s?

Sur Rodney (Sur): I moved to the East Village in the summer of '76. When I arrived here, the city was broke. The Lower East Side was mainly rubble and you could get a place to live cheaply. There was a very tight community of interdisciplinary artists, poets, writers, dancers, visual artists, and photographers. There was a lot of exchange and we made things happen for ourselves, to keep ourselves engaged as artists. We felt like outsiders, and New York seemed to accommodate that.

It was a moment where we felt anything was possible. We weren’t afraid of failure because nothing really mattered. We made our own rules. We could do anything we wanted. We were expressing ourselves, pushing ourselves to the limit, and seeing where it would go. We never expected that we would be accepted because we were outcasts. A lot of the stuff we were creating was for ourselves, to make things happen, to learn for each other. We created fame within the community we were developing, and that was fine for us. We never expected to make money—if we wanted to make money, we’d go and get a job.

Charles Busch: I was born in New York City. Even though I grew up here, I had never gone to Alphabet City. It wasn’t until 1984, when I was beginning my career in theater, that a friend, a very exotic Pakistani performance artist, invited me to see her do a piece at a bar and art gallery called the Limbo Lounge on Avenue C and Tenth Street. I had never been down there.

I was living on West 12th Street at the time. A friend and I walked from west to east, and it was like going into another country. Half the neighborhood was burned out shells, and people were warming their hands on fires inside trash cans. Then suddenly there was the Limbo Lounge. I had never seen anything like it. They didn’t just do an exhibition; they did an installation and turned the gallery into a strange, grotesque Disneyland. The audience was sort of gay, sort of straight, sort of goth, kind of punk, and everyone spoke with a Bulgarian accent even though they were originally from Cleveland—the East Village accent. The whole scene was very defined, and I felt like I was in Berlin in the 1920s.

Could you tell us about the work you were doing when these photos were made?

Busch: The night I went to Limbo Lounge for the first time, I met the owner, Michael Limbo, and arranged to perform there. The show was called Vampire Lesbians of Sodom. I threw together a piece where I was in drag to do for a weekend, and it took off. We did more shows and eventually transferred it to a regular theater. It ran for five years and is one of the longest running plays in the history of Off-Broadway.

Sur: When I first moved to New York, I started organizing photography exhibitions in Soho. I worked with photographers very strategically because they were an eye to everything that was happening. Around the time I met Don, I was producing a talk show for Manhattan Cable Television, where I was talking to artists I met that I thought were really interesting before they were discovered—just anyone I thought was doing interesting work. A lot of the talk shows were screened at the Mudd Club. The clubs were very central to bringing people together.

I was a person who stood out on the scene because of my flamboyancy, and being black in the scene, which was pretty white. People forget, in the 70s and 80s, the art scene between black folks and white folks was very segregated. They didn’t cross over too much. I was like a fly in the buttermilk.

What are some of the qualities that define the artists Herron photographed?

Sur: In every community, in every city, there are art stars. Don [wanted] specifically to meet those people, and he found some way to find someone who knew someone to put him in touch. Like, he would read Cookie Mueller in the Village Voice, then find someone who knew her so he could photograph her, and she would know three or four other people.

He realized you have to get them while you can, because you don’t know how long they will be around, because anything could happen. It was drug central around Tompkins Square Park. We were living very fast. It was very dangerous but very thrilling. You were allowed to be as crazy as you wanted. No one really cared.

What was it like being photographed by Herron?

Sur: Don found me. I don’t know exactly how we met, but he lived on Ninth Street and I lived on St. Marks Place. I remember meeting him and him saying, “I’d really like to photograph you. I am doing a portfolio for something I want to call Underground Celebrities.”

He showed me some of the photographs he had done. The concept was easy. The bathtub was the frame you would be photographed in, and it had to do with the arch of the tub being like a Renaissance painting with those angels. In terms of whether we were dressed or undressed, whether we used bubble bath, that was entirely up to us. If someone didn’t have a bathtub, he’d find someone who did, then you’d jump in and present yourself however you’d like, and he’d shoot a roll of film.

Don was a very accommodating Southern gentleman. He was easy to be around, which is why he was able to photograph so many people. He was also very ambitious. He really wanted to do this portfolio, and the Soho News wanted to do something, then the Village Voice wanted to do something, and he tried to get involved with After Dark magazine—that’s where mine was supposed to run along with Mapplethorpe’s. But what he told me is that they wouldn’t print it because our genitals were showing. I thought that was kind of odd, but nonetheless I did use the photo on the cover of a book of my poetry.

Busch: When I was firmly established as a downtown crossover artist, Don got in touch with me; I didn’t know him at all. I hadn’t really taken my clothes off—I was usually putting a lot of clothes on [laughs].

I was still living in this crummy tenement building on a very beautiful street, West 12th between West Fourth and Greenwich Avenue. Don came over to my little railroad apartment and crummy bathroom. I’m an amateur art director, so I started moving the potted plants into the bathroom, trying to dress it up so it looked glamorous. We had a lot of fun. It was marvelous to be part of that body of work. It is a great group portrait, in a sense of the wide range of personalities in fine art, theater, and film. I am so glad I said yes, even though I hadn’t heard of him and I’d barely heard of myself!

Sign up for our newsletter to get the best of VICE delivered to your inbox daily.

Don Herrron: Tub Shots is on view at Daniel Cooney Fine Art, New York, through November 3, 2018.

Follow Miss Rosen on Instagram.