‘Call It By Its Name’: Why We Need to Recognise Femicide

January 31, 2024This article originally appeared on VICE Netherlands.

For years, when a woman was killed by a partner, the media would label it a “crime of passion”, or frame it as family drama. The fact that men were doing the killing and women were victimised wasn’t mentioned at all. These terms undermine the true dynamics of femicide: toxic relationships, intimidation, control, violence.

According to the Gender Institute for Gender Equality, 1,425 women were killed by men in the UK between 2009 to 2018. Sixty-two percent of them were killed by a current or former partner. All these women were so much more than a sad statistic. They had full lives, they were surrounded by people who knew them and cared about them but did not see the signs something bad was about to happen. Nobody thinks this could ever happen to them.

Unfortunately, this lack of foresight all too common: Violence against women is still so taboo it’s hard to know what to do when you’re personally involved. This stigma only benefits abusers, too, who take advantage of the ambiguity and shroud of secrecy surrounding their relationships.

Barbara Godwaldt’s, Mariët Bosch and Odilia van de Bersselaar’s all lost women at the hands of their partners. They talked to us about why it’s so important to call these crimes what they truly are.

‘I had to live with two injustices: My sister was murdered, and her death wasn’t recognised in a fair way’

“My sister's murder is a typically case of femicide. The relationship started very intensely, where you get loads of compliments and gifts. But after a while, her husband became less sweet. At one point, he threatened to stab their dog to death with a screwdriver. Gea wasn’t badly physically abused, so for a long time I didn’t understand what kind of danger she was in. Now I’ve read about it, I know that control and intimidation are also signs that can lead up to femicide.

For a while, she tried to save the relationship. But at some point, she could no longer explain to her own daughter why she was with him. When she broke up with him, he killed her. Then he committed suicide.

After my sister's murder, I had to arrange all sorts of things for her death along with the family of the man who had done this. It was a nightmare. Local newspapers reported a “family tragedy” with “two victims”, so many people didn’t get what really happened.

Talking about a family tragedy had a huge impact. Her death was treated as if there was no killer, and his family was only too happy with this version. I had to live with two injustices: My sister was murdered, and her death wasn’t recognised in a fair way.” – Barbara Godwaldt, the sister of Gea Godwaldt, who was killed by her husband at 48

‘People think violence against women is excusable under some circumstances, as if you can provoke or deserve violence’

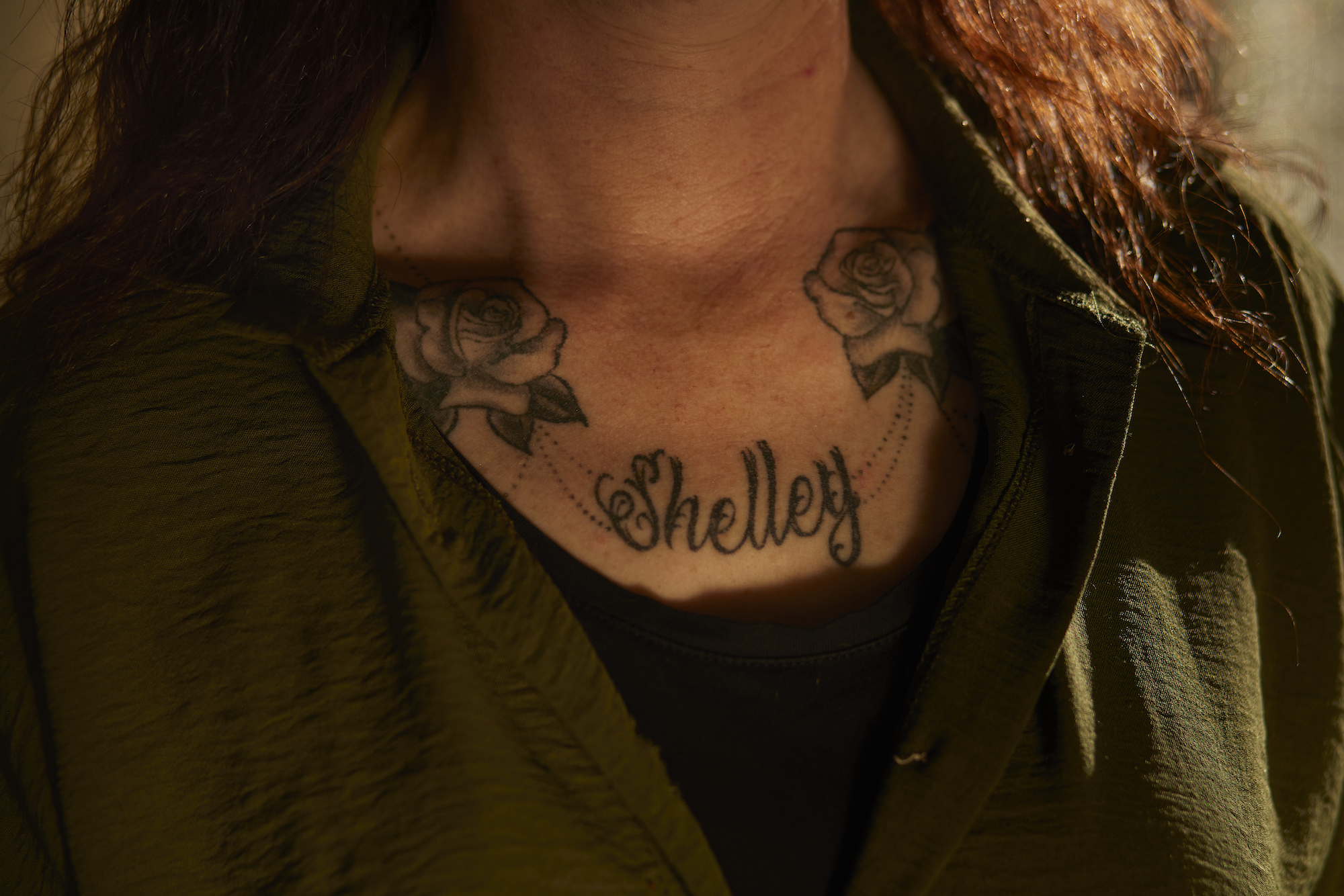

“It started two days before the murder. My daughter Shelley was sitting with her boyfriend at our kitchen table, when he suddenly started talking about a man I didn't know, who was threatening to kill my daughter. That really came out of the blue. I should’ve known then something was wrong.

She and her boyfriend had been dating for a while, but Shelley didn’t seem in love to me. He was pretty confident though, and asked if he could move in with her quite early in their relationship. They did, even though she thought it was too soon.

On the day of the murder, I was briefly in touch with her via text. At one point, I went to bed because I was feeling sick. Suddenly, my partner stormed upstairs to tell me he’d received a message saying a dead body was found in his flat, where Shelley was living. We quickly drove there, and they confirmed a woman had been murdered. I didn't understand a thing – I’d never heard of femicide.

Her boyfriend claims he impulsively killed her, because Shelley kept laughing at him while they were having a fight. He said he “couldn't take it”, as if he had no choice. I don't believe any of this. After all, he’d tried to make me suspicious of another man at my own kitchen table. That makes it clear it was premeditated. But he got away with it: He’s in jail for involuntary manslaughter instead of murder. To me, the case isn’t closed at all.

Shelley is still being blamed for her own death. His family keeps repeating that she was driving him insane, that she was mental and out of control. None of this is true, Shelley was a sweet girl. And even if she wasn’t, that’s no reason to kill her.

People think violence against women is excusable under some circumstances, as if you can provoke or deserve violence. This is why I think we should talk about healthy boundaries and red flags in relationships as early as primary school. My daughter was so young, she didn't even know how much danger she was in.” – Mariët Bosch, the mother of Shelley, who was killed by her boyfriend age 22

‘My daughter was murdered because her boyfriend couldn't handle the fact that she was an independent woman’

“My daughter Clarinda met a man, a cheerful guy, and they seemed madly in love. He had a good job and it all seemed perfectly fine. When they moved in together and my daughter got pregnant, something changed. There was a strange tension at their house. It didn't feel right, but I couldn't put my finger on it.

About six weeks after giving birth, Clarinda called me, asking me to come immediately. When I got there, she had already packed her bags. She told me then their relationship has become violent during the pregnancy. I took her away from there, and she stayed with us for a while. Later, she decided to get back with him. She wanted her baby to have a father, too.

One day, Clarinda called it quits for good, because the violence wouldn’t stop. He snapped. He stabbed her to death in the street, right in front of our house.

In hindsight, the signs had been there for a while. He was always looking at her phone, he had turned on 'Find My iPhone' so he could always see where she was. She was no longer allowed to see her friends. I was already worried about that, but when I asked questions about how things were really like at home, she avoided them. It was hard to assess how much danger she was in.

For a long time, I didn’t understand what had happened. It was beyond my comprehension. I thought: ‘This only happens to other women, not to my daughter.’ I sometimes read in the newspaper about “family tragedies”, or a woman being murdered, but that's not what it is. My daughter was murdered because she was a woman. Because her boyfriend couldn't handle the fact that she made her own choices and was an independent woman.

Clarinda's ex was known to the psychiatrist authorities and to the police because of previous violent incidents, but they did nothing about it, because femicide is not a priority. That has to change." – Odilia van de Bersselaar, the mother of Clarinda, who was murdered by the father of her child age 34