The 2020 Presidential Race Will Put Capitalism’s Evils on Full Display

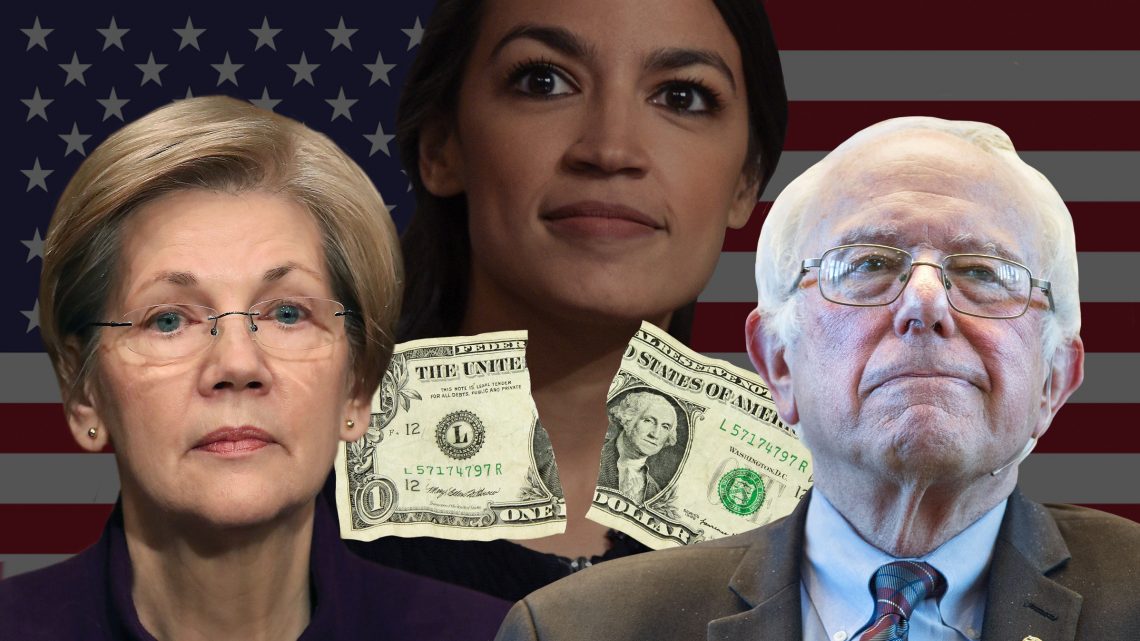

January 8, 2019 Off By Matt TaylorWhen Elizabeth Warren became the first prominent Democrat to jump in the 2020 presidential race last week, she didn't just get out ahead of potential rivals like Kamala Harris, Joe Biden, Cory Booker, and Bernie Sanders. She also laid down a gauntlet of sorts: Her campaign is centered around the perils of corruption and inequality; she's vowed to fix a broken system that gave us a shady fake billionaire as president and has failed to provide opportunities for Americans, especially people of color, to improve their lives and ascend to the middle class.

She has unique credibility on these issues. As a longtime workers' advocate who conceived of the Consumer Finance Protection Bureau, a watchdog agency that has been defanged by Trump and his cronies, Warren's national star first rose when she called out the bad actors behind the 2008 financial crisis. (She had already become something of a name as a Harvard Law professor who wrote books about middle-class debt and made appearances on Dr. Phil.) Many Democrats took to wondering after the 2016 disaster if she wouldn't have prevailed in that race as a perfect compromise between an establishment Democrat in Hillary Clinton and a burn-it-all-down outsider like Sanders.

This is the space she continues to occupy, even as the environment she's running in is radically different—and more radical, period—than 2016. Democratic socialist Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez's every movement is generating absurd amounts of press, Sanders is expected to jump into the race any day now, and poll after poll shows young people are more open to socialism and more skeptical of capitalism than their parents. In this context, it's striking that Warren proclaimed herself "a capitalist to my bones" as recently as this past summer, and was careful in her video announcing the formation of a 2020 exploratory committee to sell a vision of returning to the postwar consensus between labor and management—not erecting guillotines in the street.

"Most of us want the same thing: to be able to work hard, play by the same set of rules, and take care of the people we love," she intoned in the video. "That's the America I'm fighting for."

That critique sounds more like Barack Obama than Sanders, and that makes sense—as VICE contributor David Dayen has noted at the New Republic, Warren and the fiery socialist from Vermont represent two similar but distinct visions for the future of the Democratic Party, even as both are focused on economic populism rather than racial justice, gender equality, or the drug war. Both are harshly critiquing late capitalism, but only Sanders seems ready to propose drastic steps like nationalizing banks, even if he has sometimes been fuzzy on the details of his proposals. Warren, on the other hand, wants to reorder broken regulations and punish bad actors—not tear it all down.

It remains to be seen how nuanced Democratic primary voters will be when it comes to their generous menu of options for a challenger to a president they loathe (and fear) like none other in memory. But it's clear even a year out from the Iowa caucuses that the 2020 contest will be a once-in-a-generation battle over what democracy should look like, over how much the system can be tweaked or just destroyed, and whether Democrats can continue to function as a liberal and progressive party—or need to become more of a distinctly anti-capitalist one.

That makes it hard to stand out from the pack, but also presents an opportunity for whoever's vision of America's oligarchy cuts deepest.

"It's hard to know who's more left-wing than whom, even if you're paying very close attention," Todd Gitlin, a social movement historian and professor at Columbia who was president of Students for a Democratic Society in the 1960s, told me of the sprawling field.

It seems plausible that a few candidates will be running—or made to run—as relative centrists: Former Vice President Joe Biden got a lot of attention in October for saying that the rich are as patriotic as the poor, but that just underscores how much the contours of the debate (the Overton window, as some like to call it) have changed. Ocasio-Cortez and other activists literally occupied House Speaker Nancy Pelosi's office before the new Congress as part of a push for what the left has dubbed a Green New Deal: an ambitious agenda to cut carbon emissions while guaranteeing all Americans a good-paying job. And while they did not succeed in getting Pelosi to fully back their demands—or even preventing restoration of the miserly "PAYGO" rule mandating new spending be offset by tax increases or spending cuts—it's clear that the left is dictating the debate in a way it had not previously.

For his part, Gitlin—who has spent his career exploring the margins of activist and Democratic politics—could not recall such an ideologically wide open contest on the left, including the notoriously contentious Democratic primary of 1968 that descended into riots in Chicago.

"In '68, the fight was essentially on two issues—really, finally, it was on one, the [Vietnam] War. And if there was a second issue, it was what to do about race. If you lined up [Hubert] Humphrey, [Eugene] McCarthy, and [Bobby] Kennedy, and looked at domestic policies, I think you'd be hard-pressed to say who's the most left-wing," he told me. "The issue now is something more of a total political outlook, a general orientation. That was not really up for grabs in '68 yet."

It wasn't up for grabs in the past few election cycles, either. Barack Obama may have had to deflect attacks from the right over his "You Didn't Build That" remark when taking on Mitt Romney in 2012, and he certainly used Occupy Wall Street's 99 percent rhetoric to soak up some of that class energy in his re-election bid. But he fundamentally ran on a reform agenda that looks especially modest in hindsight—Obamacare was largely a market-based attempt at improving US health insurance, rather than the Medicare for all option that Sanders has continued to call for. It's going to be difficult for anyone running for president this go-around to get away with a status quo stance—Biden, again, may be the only one, probably by virtue of name recognition, to have a shot at threading that needle. Almost all of the other potential or announced candidates do or are likely to support Medicare for all, or something close to it, and similar policies that promise to reshape the economy.

"With Sanders, I would say, it's more substantive; with Biden, it's more that sense that he's the guy who's going to meet you for a beer after you've been working in the factory," said Christine Rididough, a longtime Democratic Socialists of America (DSA) organizer and chair of the DSA's national steering committee. "What we may see reflected more as more people get in the race is a stronger emphasis on ideas and policy."

Trump pitched himself as a businessman who knew how to save broken industries, earning union votes in key Rust Belt states and proving that many Americans really do want to hear about the crisis of the middle class. And with a new report about inequality emerging almost weekly, with a hot economy being accompanied by worse-than-ever student debt and other glaring deficiencies, it's safe to say establishing populist bona fides will be among the key qualifying factors for anyone who intends to stick it to Trump.

"This is certainly the most DSA-friendly [race in a long time]," Rididough told me. "You'd have to go back 100 years to the Socialist Party and Eugene V. Debs to see a situation where Socialist ideas are more present in the political debate. In that way, I think it's very exciting to see what's going on."

But if the debate proves to be in part about the nature of capitalism, it doesn't mean Warren and Sanders (or, for that matter, salty Midwestern populist Sherrod Brown) will emerge as the only viable contenders. As Dayen noted, almost all of the other possibles have veered toward sharper critiques of the system, with Booker decrying corporate mergers, Kirsten Gillibrand plugging a public option for banking, and Kamala Harris proposing a hefty new tax cut for the middle-class. Even Biden's allies have made noise about him embracing free college.

You don't have to be a socialist, or even close to it, to run for the Democratic Party's nomination. You just have to get the vibe.

"The big debate will not be over socialism versus capitalism," Donna Brazile, the former Democratic Party chairwoman and longtime leader who has witnessed her share of internal ideological and personality divides over the years, told me via email. "The conversations start with income inequality and the widening wealth gap."

Indeed, it's fair to wonder if all those polls showing young people are more open to socialism and suspicious of capitalism means any sizable constituency actually wants capital-S socialists, or just someone who can articulate the system's ills more sharply and convincingly than the rest. Someone who can tackle student debt, oligarchy, and the dangers to the middle class, while still operating in a framework that won't freak out your parents.

Whoever it is will also need to build a broad, multi-racial coalition, something Sanders struggled with in 2016.

"He failed to appreciate the ways whiteness has a value above and beyond class, and the ways that inequality looks differently in communities of color because of the racial hierarchy," Andra Gillespie, a professor of political science at Emory and expert on the post-Civil Rights generation of black leaders, told me. She went on to point out that one explanation for why socialism failed to generate more long-term traction in the United States was the ability of the capitalist class to exploit racial resentment and prejudice.

Then again, doctrinaire Socialism isn't the only way for increasingly left-wing people to voice their anger.

"While an increasing number of young progressives are attracted to the idea of socialism—inspired by Sanders in 2016 and politicians like AOC now as well as their perception that capitalism is an inherently inegalitarian order—many of the same ones are open to a presidential candidate who does not identify as such but does, like Warren, have a determination to roll back corporate power and empower workers, through unions and other means," Michael Kazin, a Georgetown history professor and co-editor of the lefty journal Dissent, told me via email. He added that while, say, DSA-style activists might be dubious of almost everyone in the emerging 2020 field, "most are more practical about electoral choices than the image of dogmatic radicalism suggests."

But if nothing else, as charismatic centrist favorite Beto O'Rourke's candidacy showed in Texas—where his refusal to take PAC money was a factor in his appeal—everyone will have to at least gesture toward a newfound activist rage toward the ruling class.

"What's beginning is not the coming of the new social democracy [so much] as it is a period of sorting out and argument, which is necessary," Gitlin told me, adding, "It's going to be a discussion the likes of which the Democratic Party has not had in my lifetime."

Sign up for our newsletter to get the best of VICE delivered to your inbox daily.

Follow Matt Taylor on Twitter.