Myanmar’s Coup Has Opened the Floodgates of the Southeast Asian Drug Trade

December 20, 2021In the back of the truck was enough methamphetamine to get more than 65 million people high—but the driver said he didn’t know anything about that.

As far as he was concerned, the 22-year-old would later claim, he was just transporting crates of empty beer bottles through Bokeo Province, a hilly region in the northwestern corner of Laos that happens to sit at the heart of the Golden Triangle. The mountainous area, where the borders of Laos, Myanmar and Thailand meet, is a wellspring for the world’s illegal drug trade.

Less than 80 miles away was the border of Myanmar’s Shan State, one of the largest meth-producing areas on the planet. It was the night of Oct. 27, 2021, when police raided the 12-wheeler and found, hidden among the stacks of bright yellow Lao Brewery crates, more than 1.5 tonnes of crystal meth, or “ice,” and over 55 million yaba tablets, otherwise known as “crazy pills.” It was and still is the biggest single drug bust in Asia’s history, and on the surface level, a major win for narcotics police.

It was also, however, just the latest case in a rapidly accelerating trend: a growing deluge of illicit substances that has spilled over the Burmese borders and flooded Southeast Asia throughout 2021. The Golden Triangle, that notorious nerve centre of the international drug trade, is flourishing more than ever. And much of that, it seems, can be traced back to a single, pivotal event on the morning of Feb. 1: Myanmar’s military launched a coup d'état against Aung San Suu Kyi’s democratically elected government and seized control of the country. Ten months later, there are fears that the increasingly embattled nation could start resembling a narcostate.

The fallout from the putsch has turned Myanmar on its head, diverting authorities’ attention toward matters of civil unrest and rending open cracks in the country’s border security. The drug traffickers, forever opportunists, are capitalising on the shake-up. Huge quantities of drugs that previously would have been caught at the source are now flowing through increasingly porous sections of the border and into the lucrative markets of Asia-Pacific.

Two days after the beer-truck drug bust on Oct. 27, Jeremy Douglas, Southeast Asia regional representative for the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), told VICE World News that the historic seizure was “no doubt connected to the deterioration of security and governance in [Myanmar’s] Shan State.”

The noticeable uptick in drug trafficking activity in Asia overall, he later added, appears to be directly linked to the coup.

“The recent surge in supply hitting the region just happens to have happened as the situation deteriorated,” he said. “Hard to see the two things being unrelated.”

The Burmese army seized control of Myanmar in the early hours of that February morning—12 weeks after the National League for Democracy (NLD) won the country’s democratic election by a landslide.

The military, refusing to accept the inevitable defeat of its own party in the polls, had been leveling accusations of electoral fraud against the NLD for months. Finally, in a pre-dawn raid, they swooped in and detained civilian leader Aung San Suu Kyi, President Win Myint and other senior members of the party, declaring a 12-month state of emergency and handing all executive, legislative and judicial powers to Senior General Min Aung Hlaing.

In less than 24 hours, the civilian government was deposed. The junta was now in charge.

Within days, the nation erupted into protests. A wave of anti-coup resistance rippled across the country, as opponents of the military power-grab took to the streets and dozens of guerrilla and grassroots militias emerged to denounce the junta. By the end of June, over 4,700 anti-coup demonstrations reportedly took place in Myanmar.

Authorities have met the dissent with a campaign of military violence and mass arrests. The country is spiraling ever deeper into crisis—and the imploding security situation has, inevitably, diverted police away from the front lines of the war on drugs.

“The operational focus of the MPF [Myanmar Police Force] has very noticeably and publicly shifted to dealing with protest, social unrest and almost counterinsurgency efforts,” said Douglas.

This created a golden opportunity for drug traffickers. Richard Horsey, senior Myanmar adviser to the International Crisis Group (ICG), told VICE World News that while the rest of the Myanmar economy has crashed under the weight of the pandemic and coup, it's a good time to be in the drug business.

“The military and police are focused on trying to suppress a determined resistance movement, and drug issues have even less attention,” said Horsey. “The criminal organisations and militias have seized the opportunity to ramp up [drug] production. And the Myanmar military has a host of new enemies and no interest in picking fights with the militias involved in the trade.”

As the security situation within Myanmar collapses, the shockwaves of the February coup are reverberating down the supply chain. The country’s police force is hamstrung, and drug syndicates in Shan State appear to be making meth while the sun shines—lighting a fire under their operations and pumping huge quantities of drugs through widening cracks in the country’s international borders.

As Douglas put it: “Conditions on the ground are basically perfect for traffickers.”

Seizures have noticeably picked up in Thailand, Laos, Cambodia and Malaysia since at least June, as well as further afield in countries like the Philippines and Indonesia. By September, Malaysia’s narcotics crime agency had already seized more than $180 million worth of illicit substances—a 150 percent increase compared to the entirety of 2020. Thailand has similarly clocked record levels, while Laos has seen six times as much meth seized within its borders this year compared to last.

Large-scale seizures have also persisted into late 2021. Earlier this month, Thai police pulled over a monk driving a pickup truck with more than 5.6 million yaba pills in the back. Days earlier, authorities in Chiang Rai pulled over another truck carrying 2.6 million pills, and days before that, Indonesian police seized 100 kilograms of crystal meth packaged up inside distinctive, green-and-gold Chinese tea packets.

According to Douglas, almost all of these drugs can be traced back to a single source: the rugged jungles and frontier towns of Shan State. Nuzzling the borders of China, Laos and Thailand, Shan has long been a regional epicentre for the production of yaba. More recently, it’s also become a fountainhead for crystal meth.

“Supply in the region is almost entirely sourced back to remote and border areas of Shan,” Douglas said. “Intel, methods used by traffickers and forensics all point to the fact [that] drug supply in the region emanates largely from [there].”

The syndicates are diversifying and expanding their operations, he explained—and countries right across the region are feeling the effects.

“The impact is being most acutely felt in Thailand, Laos and Malaysia—but Hong Kong, Cambodia, the Philippines and Indonesia are reporting large drug seizures that can be traced back to the Triangle.”

Myanmar has a long and fraught history with drugs. Since the 1950s, the country has straddled one of the largest opium-producing areas in the world, and remains the second-largest global source of the drug after Afghanistan. Most of that, too, comes from Shan, which is the largest of Myanmar’s administrative divisions by land size and home to a number of armed ethnic groups fighting their own campaigns for self-determination.

Many of these ethnic militias fund their fight by drug trafficking, working in lockstep with the various criminal syndicates who harvest and produce illicit substances in Shan’s highland areas. In more recent years, these groups have pivoted their operations away from opium to focus more aggressively on meth.

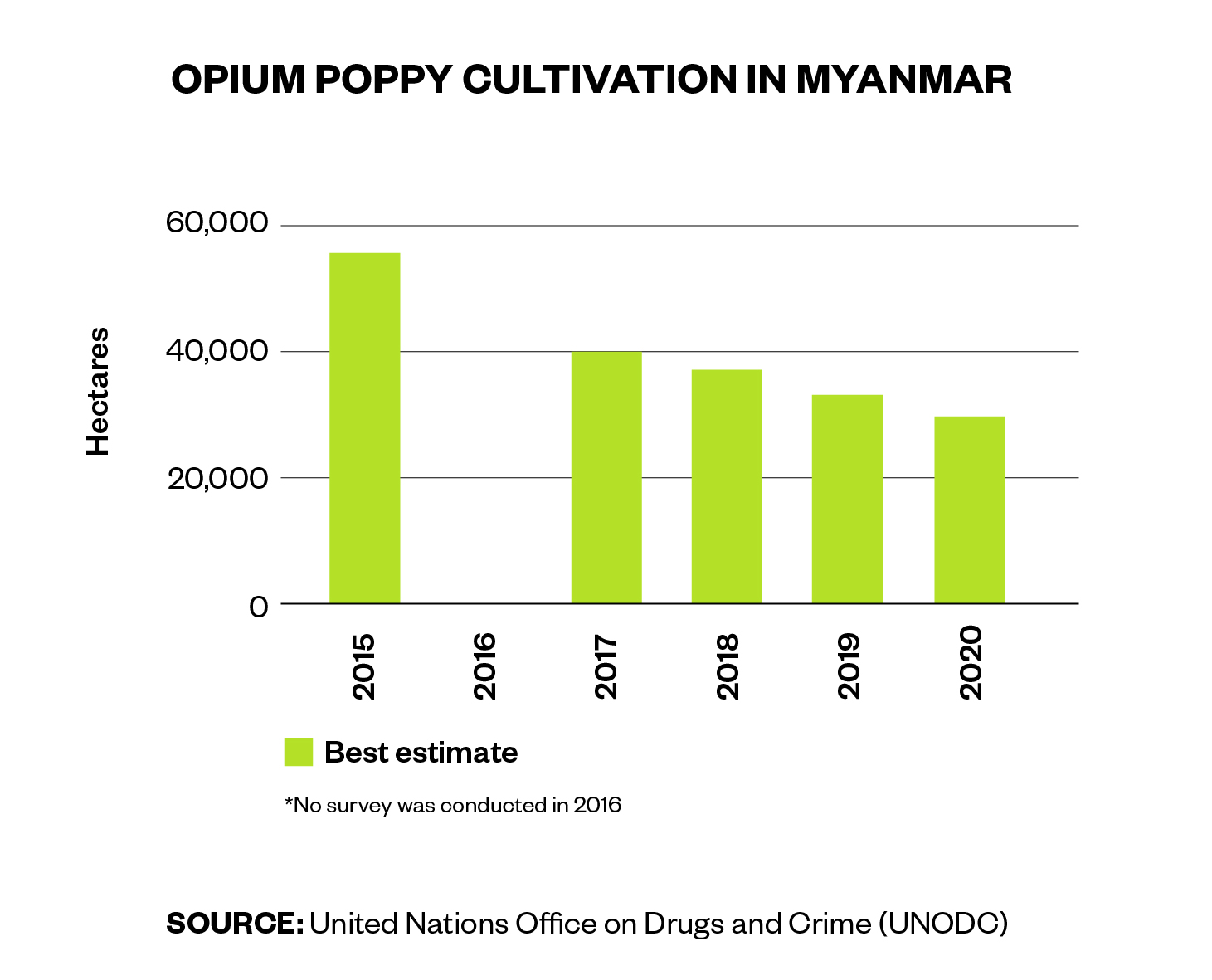

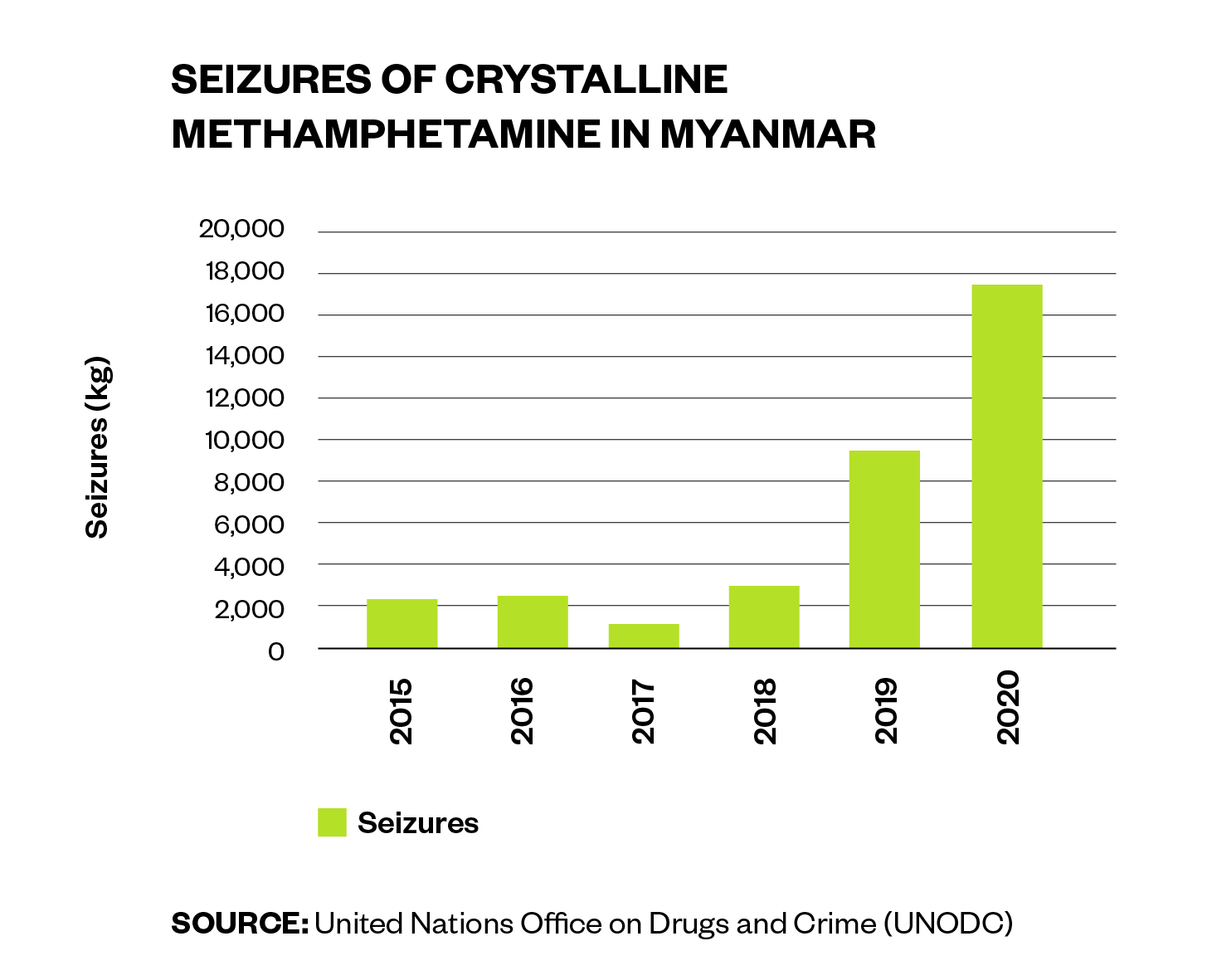

Since 2015, opium poppy cultivation in Myanmar has declined year after year, while production and trafficking of methamphetamine has spiked. Between 2015 and 2019, the number of meth tablets seized by Myanmar authorities more than doubled, then more than tripled again in 2020. Similarly, the amount of crystal meth seized in 2020 saw a 667 percent increase over 2015 levels.

Like the beer bottle haul in Laos, when removed from the bigger picture, these historic seizures might seem to be a win for the narco police. But despite the large and growing amounts of meth getting caught by authorities in Myanmar over the past half-decade, the retail prices of both crystal meth and meth tablets have largely remained stable—indicating minimal changes to their availability on the market.

In some cases, prices have plummeted, indicating a surfeit of supply. So while Burmese narco police might appear to be winning more battles against drug syndicates, they’re demonstrably not winning the war.

“Conditions on the ground are basically perfect for traffickers.”

Horsey pointed out that Burmese authorities have never been particularly effective at stemming the flow of illicit substances, hampered as they are by a lack of resources, a lack of political will and corrupt authority figures who are often complicit in the drug trade.

Since February’s coup, however, enforcement has gone from bad to worse.

“Myanmar's status as one of the world's largest illicit drug producers is only possible because of criminal justice failures,” Horsey explained. “Petty and high-level corruption, including in the police force; poor capacity and training; insufficient political priority given to these issues; and the fact that much drug production takes place in areas controlled by armed militias where police operations need Myanmar military approval and support.”

Horsey acknowledged the work of upstanding anti-drugs officers responsible for significant seizures of precursor chemicals and drugs within the country, but even these efforts have taken a dive in 2021.

While in previous years Burmese authorities boasted of major drug busts and lab raids within Shan State and beyond, Soe, a Myanmar-based researcher studying drug seizures, told VICE World News that throughout this whole year there has been no reported raid of a major production site or facility anywhere in the country.

“What we [can] conclude about drug seizures going on in the middle of the political crisis in Myanmar [is that] while there are some police there, they are deployed in major cities and other areas to crack down on protesters,” said Soe, who has been given a pseudonym to ensure their safety.

“We see less information about ice seizures than 2020—but that doesn’t mean that the numbers of drugs produced in Myanmar and trafficking inside Myanmar is in decline. I think the production and trafficking rate is going as usual.”

“As usual” means the continuation of an all-time high for producers, traffickers and syndicates in Southeast Asia. The UNODC in June estimated the value of the region's drug trade to be somewhere between $30.3 billion and $61.4 billion—much of which can be traced back to production zones within the Golden Triangle—and syndicates continue to ramp up their operations.

For those based within Myanmar, being able to get drugs across the borders is a big deal. While a gram of crystal meth sells locally for about $15, the same amount can fetch more than $100 in countries like Indonesia. If they can get their product out further to somewhere like Japan, one of the world’s most lucrative meth markets, traffickers stand to make as much as $613 per gram.

“The regional market is enormous and can pay, and there is room for growth, while the local market is limited and prices are low,” Douglas explained. “Profits are made [by] pumping out product for Asia-Pacific, not the country itself.”

The deluge of drugs flowing out of Myanmar also shows no signs of slowing. The global COVID-19 pandemic has done little to dent drug operations in the Triangle, as traffickers have proven resilient and innovative in the face of border closures, flight restrictions and shipping problems. Douglas predicts that once international travel starts up again, syndicates will be ready to take advantage.

Similarly, within the borders of Myanmar—a nation that continues to languish in the throes of violence, conflict and poverty—things look unlikely to improve. The country’s economy has tanked in the wake of the February coup, its currency has depreciated by at least 60 percent, and basic state services have ground to a halt amid increasingly fractious relations between the military and the general populace.

“The Myanmar military has a host of new enemies and no interest in picking fights with the militias involved in the [drug] trade.”

While Golden Triangle drug barons seize the moment to consolidate and expand their multinational drug empire, Soe suggested that ongoing economic instability is likely to fuel the drug industry on the domestic front, as more people are forced into illicit lines of work in order to put food on the table.

Experts and international commentators have long wondered whether Myanmar may be at risk of becoming a narcostate, a country whose official institutions are propped up by the profits of the illegal drug trade. Parts of the country already fit the bill. In 2019, the ICG observed that Shan State’s “Drug production and profits are now so vast that they dwarf the formal sector… and are at the centre of its political economy.”

As the nation’s licit economy becomes increasingly supplanted by the black market, and the military usurpers allow more space for drug lords within its borders to operate, Myanmar at large has the potential to head down a similar path.

“As the political crisis is going on, that is a very dangerous time for that sort of [drug-producing] situation in Myanmar,” Soe told VICE World News. “A lot of people will face some kind of food insecurity and income problems in the next two or three years. And when they have nothing to do, they have to do something so that they can feed their families.”

This isn’t new. Last time the Burmese army launched a coup d'état, in 1962, the military usurpers pitched the nation into economic freefall in pursuit of the so-called Burmese Way to Socialism. By the 1980s, Myanmar had become one of the poorest countries in the world. And as Chao Tzang Yawnghwe, son of Shan leader and Myanmar’s first president Sao Shwe Thaike, explained in a 1982 essay, such poverty only served to oil the wheels of the “fast-rolling opium bandwagon,” opening up space for an entrepreneurial black market and “[delivering] the economy into the hands of the opium traffickers.”

In this way, Myanmar’s drug trafficking problem runs wider and deeper than just a matter of crime. The flourishing drug market is intrinsically rooted in, and draws its lifeblood from, the various political, social and economic catastrophes that continue to plague the Burmese people.

Unless the manifold problems that precipitate and fuel the drug market are resolved, Soe suggested, the high tide of narcotics flowing out of the Golden Triangle will continue to rise. And with the February coup ushering in a new chapter of political upheaval in Myanmar—one with little prospect of resolution—the forecast is looking as auspicious as ever for the country’s roaring drug industry.

“Drugs are a byproduct of the political strife and conflict in the country. There is no way to solve the drug issue unless the country finds a political solution to end the decades-old conflicts and improve the governance system,” said Soe.

“The country is in the conflict trap.”

Follow Gavin Butler on Twitter.