This Risky Hack Could Double Access to Ventilators as Coronavirus Peaks

March 19, 2020An emergency medicine physician says she and a colleague invented a way to connect four patients to a single ventilator, a hack that could significantly increase the capacity of overburdened hospitals during the coronavirus pandemic.

Doctors Greg Neyman and Charelene Irvin Babcock published a pilot study of the technique in Academic Emergency Medicine in 2006. Babock is now an emergency medicine physician at a hospital in Detroit, Michigan and posted a YouTube video on March 14 describing the technique.

“Because of the Covid-19 pandemic, many healthcare providers are struggling with a situation where they may have more than one patient needing ventilation and not enough ventilators to go around,” Babcock said in the video. “That’s why I’m putting this YouTube together. So I can show you how to modify one ventilator to ventilate more than one patient.”

In an interview with Motherboard, Babcock said that actually using it on coronavirus patients is a tough call, but a potentially life-saving one in a last-resort situation. These types of decisions—about who to treat and who to let die—are being made daily by doctors in Italy, and experts worry American hospitals could soon be overwhelmed, too.

She said she’s not sure if she’d use the technique herself if she ran out of ventilators.

“That would be a true test,” she said. “Let’s say 10 people are dying in front of you and you have one ventialtor. That’s a tough call. I would talk to the family of the four best candidates and say, ‘Look, I could let three of you die or I could try all four, [but] we’re rolling the dice. It hasn’t been done before. And if it doesn’t work, we’re going to have to take three off, but this is probably the only chance they have of trying to survive.’”

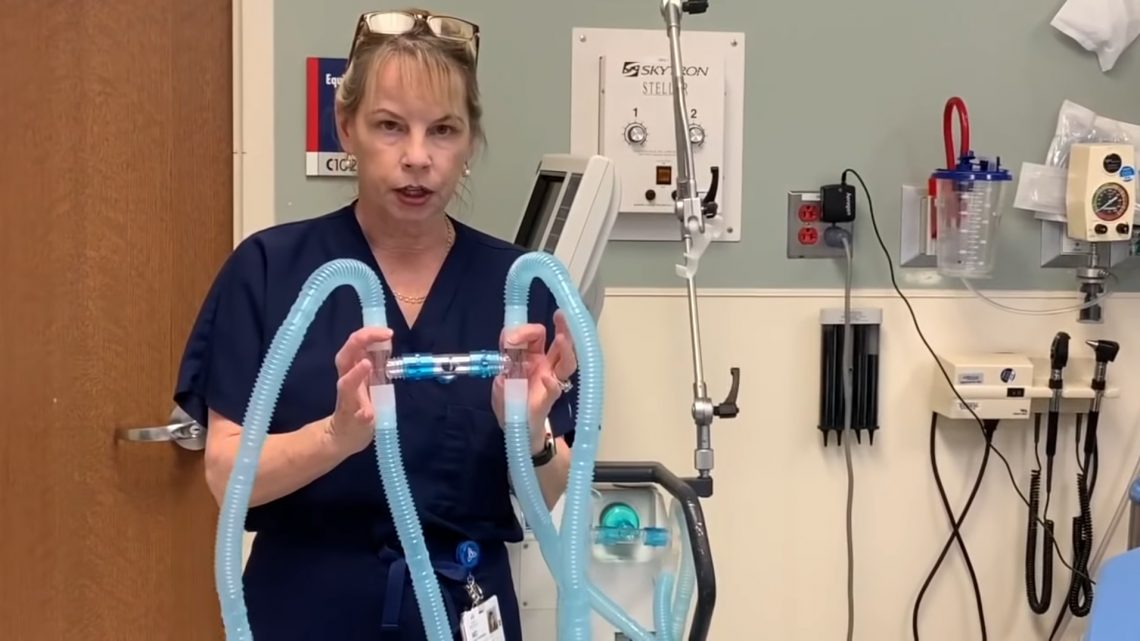

The technique is remarkably simple. “Four sets of standard ventilator tubing were connected to a single ventilator via two flow splitters,” the study said. “Each flow splitter was constructed of three Briggs T-Tubes which included connection adapters with the valves removed.” In Babock’s video, she said the adapters were 22mm in size.

Basically, any kind of T-shaped tube can be adapted to extend the ventilator to more than one patient. Babock’s video has gone viral, and she told Motherboard in a phone interview that she put together the four way adapter set in her YouTube video in 15 minutes using supplies her hospital already had.

She said her family urged her to share her knowledge with the world. Doctors in Italy are already having to make agonizing decisions about who to treat and who to send home; American doctors warn that we could soon face the same problems here.

“It’s only been done in test lungs,” she said over the phone. “But it’s probably better than nothing in dire circumstances. We don’t know how bad it’s gonna get. [Italy] is so overwhelmed with people that will die without ventilators and they don’t have enough ventilators. Sometimes trying something almost MacGyverish is better than doing nothing.”

In both her YouTube video and during our interview, Babock urged caution.

“It hasn’t been studied in humans, but it has been studied in test lungs and animals with normal lungs,” she said. “In this particular infection, the lungs are not normal. That’s where most of the pathology is...so a lot of the dynamics will change substantially.”

In the study, a modified ventilator was able to properly intubate four sets of simulated lungs.

“This has not been tested in humans,” Babcock said in the video. “But it has been used on humans.”

In the wake of the Las Vegas shooting in 2017, patients overwhelmed the local emergency room. Doctor Kevin Menes was working in the emergency room that day, remembered the study, and used it to save lives when the hospital ran out of ventilators.

“What he came up with was that if you have two people who are roughly the same size and tidal volume, you can just double the tidal volume and stick them on Y tubing on one ventilator,” Menes wrote of his experience in Emergency Physicians Monthly.

Different patients have different lung capacities, which means you can’t just hook up random patients to the same ventilator. “You want to make sure the lung sizes are the same on all four portions of the cycle,” Babcock said in her video. “You wouldn't want to put a pediatric patient with an adult patient because that wouldn’t make sense. It wouldn’t be able to make sure the same volume is delivered everywhere appropriately.”

The length of tubing has to match, the size of the patient's lung capacity needs to match, and there’s always a danger of cross contamination between patients. “Likewise, you want to make sure the resistance is the same. You wouldn’t want to put a patient with severe bronchospasm [sudden contractions of bronchial muscles in the lungs] with a patient that does not have bronchospasm because that would.”

Gregory Barefoot—a physician's assistant (PA) and former chief PA at the Trauma and Surgical Critical Care service in Columbia, South Carolina—told Motherboard in an email that the Neyman/Babcock method looked good in theory, but needed to be practiced with caution. Barefoot pointed out that the Las Vegas shootings victims were trauma patients who didn’t need long term ventilation. The same isn’t true of COVID-19 patients.

“Some of the patients that are suffering from COVID-19 are having to be ventilated for over a week in many cases,” Barefoot said. “Ideally, the patients that would be grouped together would be of similar disease pattern, body habitus and with similar premorbid health status ...a mode of ventilation should fit the patient, not the other way around. Each person will interact with a ventilator differently and it is hard to individualize care amongst four patients with one ventilator.”

Babcok isn’t ignoring these dangers and she agreed with Barefoot’s assessment. “This is off label use of the ventilator,” she said in the video. “The ventilator is made for one person...I always hope you would never need to use it in this way but you can never predict what will happen in a disaster.”

Babcock works at St. John’s Ascension hospital in Detroit Michigan and said that, at the moment, they’re accommodating every patient just fine.

“In a big city like Detroit, we’re prepared for a disaster situation. We have a cache of emergency ventilators available,” she said. “ Now I can’t guarantee we’re not going to go past that. But right now, we have a lot of capability...right now, at St. John’s, I’m not worried about not having a ventilator.”

“In an ideal world, we wouldn't need to use this today or tomorrow. In an ideal world we could potentially look at studying an animal and figuring out what are the potential applications that make it better suited for a [respiratory distress syndrome] model,” she said.

But this isn’t an ideal world and Babock said she couldn’t not share what she knew.

“Saying nothing when I know this information would not have been the right thing to do,” she said. “I hope I’ve pointed out the caveats...but I think it’s worthwhile to start a discussion about alternative ways to save lives using what we have now.”