This Is How People Can Actually Afford to Live in Seattle

November 14, 2018Seattle has always been a boom-and-bust town. This is a city where the first population surge came during the Gold Rush of the 1890s, when the entrepreneurial leaders of what was then an isolated regional backwater marketed the place as a gateway to the riches of the Yukon. But as difficult as that is to imagine now in what some locals call Amazonia, where tech-money-inspired skyscrapers rise out of the ground all over downtown, there have been more fallow periods, too. During the economic downturn of the early 70s, a billboard went up out near the airport asking the last person leaving Seattle to turn out the lights.

And as politically progressive as the city’s reputation now is, economically, the place remains a freewheeling frontier town at heart, with the pursuit of capital the only consistent driving force from the 19th century to the present.

Since 2010, Seattle has increased in population size by a whopping 18.7 percent, the fastest rate of growth among the biggest 50 cities in the United States. For perspective, the Seattle Times noted that the city’s population growth of 114,000 in the first seven years of this decade was roughly the same amount it grew in the previous 30 years, back to 1980.

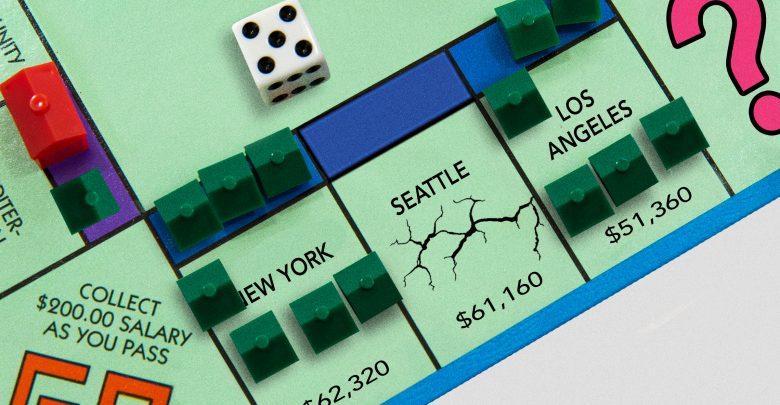

Construction is everywhere: As of July, Seattle led the nation in tower cranes for the third year running with 65 in operation, easily beating out second-place Chicago’s 40. But the cost of living has skyrocketed right alongside the population numbers: This is now the third-most expensive city in the nation to buy a home, per Zillow data, up from tenth just four years ago, leapfrogging New York and Los Angeles in the meantime.

“It’s been a lot of high-income jobs, and couple that with not building enough new housing, and that’s where you see a lot of rising costs,” explained Taylor Marr, senior economist at online real-estate brokerage Redfin.com, noting that most of the growth was in the tech sector.

Another telling stat, from the US Census Bureau: The number of Seattle families with an income of at least $200,000 is now greater than the number making less than $50,000. Among the 50 largest US cities, Seattle was one of just three so skewed toward the top, alongside San Francisco, the metropolis with which it is so often compared. Median income has ticked up north of $80,000.

And the exorbitant demand on the city’s housing supply isn’t likely to change anytime soon.

Amazon, the headquarters of which has utterly transformed the South Lake Union neighborhood near downtown, continues to expand with seemingly no limit to its ambitions, even as it plans to open up new headquarters elsewhere. (Reports that one of two new Amazon HQs might go to Queens, New York, were said to spike housing prices there even before the news was official.) Google is currently building a 900,000-square-foot campus near Amazon, and Expedia’s new 40-acre complex alongside Elliott Bay is set to open in 2020.

To the less-than-rich holding out hope that the city might push back against the companies driving rising costs, this year’s “head tax” debacle was illustrative—and depressing. In May, the Seattle City Council passed a new tax on large businesses that it hoped would raise $47 million to fund affordable housing development and homelessness services, only to reverse course and repeal the plan a few weeks later under pressure from the local business community (and Amazon in particular).

“If the demand keeps going, you’re just going to keep weathering the storm,” said James Young, director of the Washington Center for Real Estate Research at the University of Washington. “To kill that demand, you’ve got to kill job growth. And nobody wants to do that. There’s no incentive.”

Fixing the supply side is an even tougher proposition. Geographically, Seattle is bottlenecked by Puget Sound to the west and Lake Washington to the east, with the Cascade mountains further out that way also limiting sprawl. Population growth has spread all the way down to Tacoma in the south and Everett up north, but there’s only so far it can go before commute times get too unwieldy.

Zoning laws are another complication. Especially compared to other, smaller up-and-coming tech hubs like Austin, Nashville, and Raleigh, building permits are tough to come by in Seattle, according to Marr. Wide swathes of the city are zoned only for single-family homes, ensnaring the few parts of town where tall, dense housing is allowed with countless construction sites.

One needn’t dig very deep for discouraging stats on what all of these means for Seattleites without six-figure tech salaries.

Though the official poverty level for a single-person household in America was $12,140 in 2017, an individual in King or Snohomish counties earning $50,400 or less was considered low-income. Stated more bluntly: A middle-class income throughout much of the country amounted to near-poverty status here. Per mortgage research website HSH.com, metro households now need to make $109,274.91 per year in order to afford the principal, interest, taxes and insurance payments on a median-priced home. That’s a payment of $2,549.75 every month, and that’s if homebuyers are putting down 20 percent up front. At 10 percent, the required salary increases even further: to $129,018.81.

The rental market has also been trending toward the extreme. Per the National Low Income Housing Coalition (NLIHC), at minimum wage—currently a sliding scale from $11.50 to 15.45, based on size of employer and benefits—you’d have to earn $61,160 (or work over 102 hours a week) in order to afford what it described as a modest one-bedroom at Fair Market Rent in Seattle.

Those numbers are disheartening to those lower on the economic food chain precisely because this can be such a fantastic city to live in. The natural scenery is breathtaking, the white-capped mountain ranges towering over perfect blue waters. It’s still cheaper than San Francisco and, locals tend to insist, more cosmopolitan than Portland. Assuming you can handle the rain and long winter nights, the weather is mild, encouraging outdoor activities all year round.

To those captivated by the region’s beauty, and its culture, this can be a tough place to leave. So how do those who stay—or insist on coming even without a fancy tech job—make it work?

Where Do They Live?

At every income level, the viable neighborhoods in which to rent have shifted further outward from the city center with each passing year. The Central District is the starkest example of the ongoing gentrification: Once the cultural hub for Seattle’s African-American community, most of the oldest families have long since been priced out. West Seattle and Columbia City were known until recently as havens for cheap rent, thanks to the relative inconvenience of getting downtown, but even those neighborhoods are starting to change.

Median Income: Grade school teachers Daniel Talevich and his wife Kristy were rocked by one of those now-infamous Seattle rent increases on their Lower Queen Anne apartment two years ago. The rate for the two-bedroom was originally $1,400, which they knew was below market value, but they were still stunned when their landlord gave them 90 days notice on a hike to $2,000.

“We’ve been able to make it work, but it’s not always ideal,” Talevich told me, noting they had Kristy’s sister move into and pay rent on their spare bedroom to offset costs.

Rob Rudd is a sous chef who lives in one of the obnoxiously named new apartment buildings popping up around the edges of trendy Capitol Hill. (His complex is named Anthem; its official slogan: “Live your Anthem.”)

“I make it work because I’m currently trying not to think of my future,” Rudd said. “If I was trying to save money and live where I live, I literally couldn’t go out and do anything.”

Minimum Wage: Megan Garcia, who moved to Seattle from Honolulu, Hawaii, back in January, works in Pike Place Market for a small business that sells honey. Noting that Honolulu isn’t all that cheap a place to live itself, Garcia has been less taken aback by the cost of living than she feared she might be.

Having diligently researched the housing market before she arrived, she was able to land a studio apartment not too far from the Taleviches in Lower Queen Anne.

“Seattle is a very flexible place, budget-wise, if you’re willing to shop around," Garcia said from her stall kitty-corner to the market’s famous fish tossers.

But for those on or near minimum wage, if you're not staying in cramped quarters with multiple roommates or a significant other, living outside the city limits often feels like the only option.

How Do They Get Around?

Having famously voted down a rapid-transit system that would have been 75 percent funded by the federal government in the early 1970s—it eventually became Atlanta’s MARTA—Seattle’s public transit is a major weakness. That’s a big part of the reason it’s so difficult for the city to sprawl further north and south.

This affects locals of every economic background, from the rich folks sitting in congested traffic on the I-90 and 520 bridges trying to get over to the moneyed east side to those making multiple bus connections en route to lower-paying jobs. Fares for the Link light rail system, which runs exclusively north/south from the University of Washington past the SeaTac international airport, range from $2.25 to $3.25 one way and up to $6.50 round trip. Adults pay $2.75 per bus ride, and the 520 toll bridge over Lake Washington maxes out at $6.30 on weekday rush periods.

As much as locals try and do save on transit when they can, there’s only so much one can cut back on in a city where the rapid transit serves such a narrow sliver of the populace.

Garcia, who doesn’t have a car and travels by bus to and from work, considers herself fortunate that she was able to find a place so close to the city center. Because of her income level, she qualifies for a discounted ORCA LIFT transit card, dropping that price to $1.50 per trip.

What Do They Eat?

Seattle has a vibrant and diverse food scene, with an abundance of fresh seafood and flavors from all over the world, and South Pacific and Asian cuisines particularly well represented. There are cheaper options, too, of course if you know where to look. Walking and eating around the International District, for example, is a budget-friendly way to spend a weekend afternoon. And if you’re craving old-school Americana, at Dick’s Drive-In—a beloved local institution that has been grilling up meat patties since 1954—cheeseburgers and fries each go for just $1.75.

Median Income: Rudd works at a German biergarten on the edge of First and Capitol Hills, and due to his chosen industry as well as his passions, this is most often where he funnels his (limited) disposable income.

“I live paycheck to paycheck,” Rudd said. “But all of that goes into going out and trying new foods and new restaurants. I can’t afford to do much of anything beyond that. I mean, I’m not going to Seahawks games and dropping $275 on the cheapest ticket.”

For the Talevich family, eating out is often where they choose to skimp. “We’re careful,” Daniel said. “We don’t go out to dinner too often, and definitely not to fancy restaurants. … Most often, we end up ordering takeout.”

Minimum Wage: Emily Fisher, who moved to Seattle from her hometown in Montana eight years ago, lives in the Magnolia neighborhood tucked away in the city’s northwest. She shares a place with her boyfriend, which helps with rent, but even then, she works both as a barista and at a tattoo parlor to make ends meet.

“I haven’t been going out to eat,” she said. Asked whether that was out of economic necessity or because that’s just not high on her wish list, she answered: “Both.”

Can They Have Fun?

Seattle’s music scene has been world-renowned ever since the grunge craze of the early 1990s. And when it comes to sports, the Mariners, the city’s Major League Baseball team, missed the playoffs again this year, but NFL’s Seahawks have at least injected some life into the scene in the last half decade or so. The Sounders, the soccer team, also have an oddly rabid following for this part of the world.

For those without money to burn, it’s about picking your spots. Hiking and other outdoor activities are hugely popular, and inexpensive to get into—at least at first.

Median Income: Daniel and Kristy’s situation was recently complicated by one major expense in particular: They got married this summer in Kristy’s native Spokane. “That was difficult, because we definitely kept costs in mind when we were planning the wedding,” Daniel said. “We did a food truck instead of a plated meal. For our DJ, we went with a friend of a friend.... We were able to have a great wedding, but we definitely needed to be budget conscious.”

While they’re careful about when and where they go out to eat, they’re more apt to splurge by traveling. And even then, Daniel said, "we often try to camp or to find a cheap Airbnb.”

Minimum Wage: Garcia, who is both an amateur dancer and musician, budgets herself funds to attend at least one ballet or dance recital per month. "That’s kind of keeps me happy, I’ve found,” she said.

Otherwise, she’s most often found at home working on her music or taking advantage of some of the city’s other, cheaper (read: free) activities.

“I also like going for long walks around Seattle,” she said. “That’s one of my favorite things to do.”

Meanwhile, going out to the city’s many dive bars is essentially Fisher’s sole means of blowing off steam. Otherwise, she’s a homebody, forgoing the city’s music and professional sports events to stay in and unwind with Netflix when she’s got rare downtime.

“It’s hard,” she said. “I work nine-hour days, every single day. I don’t get weekends—or days—off.”

For as much and as quickly as it’s changed, Seattle still isn’t the Bay Area. Even those on the (relatively good) minimum wage can theoretically make it work, if they’re willing to put in an ungodly amount of hours and live in a less fashionable part of town.

The worry is that this might not be the case for long. Though the housing market has finally recently started to cool, experts tend to agree it’ll tick back upward before long—especially given the reticence of the powers that be to impose the slightest limit on the breakneck pace of growth.

So how do people actually afford to live in Seattle? The lazy answer is to land a lucrative tech job. For the rest of us, making it work often boils down to an either/or: Skimp on the food and cultural scenes that make the city appealing in the first place, or willfully ignore the well-being of your savings account.

Rudd really did say it all when he opined: “I make it work because I’m trying not to think of my future.” In that, he’s far from alone.

Sign up for our newsletter to get the best of VICE delivered to your inbox daily.

Follow Matt Pentz on Twitter.