In ‘Kerbal Space Program 2’, the Fun Is in the Failure

February 20, 2023To err is human, but to forgive… that’s Kerbal.

That was my overarching feeling as I played Kerbal Space Program 2 (KSP2), the sequel to the beloved simulation game of the same name, at a special event held at a real space center to preview its release on early access on Friday, February 24.

In the world populated by Kerbals, the game’s cartoonish humanoids, there is no rocket too faulty for the launchpad, no trajectory too dangerous to chart, and no Kerbal whose love for spaceflight is tempered by even the remotest sense of self-preservation. This resolute affability in the face of certain doom was a big part of the charm of the first iteration of KSP, initially released in 2011, and it continues to serve as a reminder of the essential Kerbal message—failure is fun—in the sequel.

It's a good thing that failure is fun in KSP2, because that’s all I did during my two hours of tinkering with the much-anticipated sequel at the preview event, which was held at the European Space Research and Technology Centre (ESTEC), Europe’s biggest space technology site, located in the seaside town of Noordwijk, Netherlands. (Private Division, the publisher of KSP2, organized the event and covered our travel expenses.)

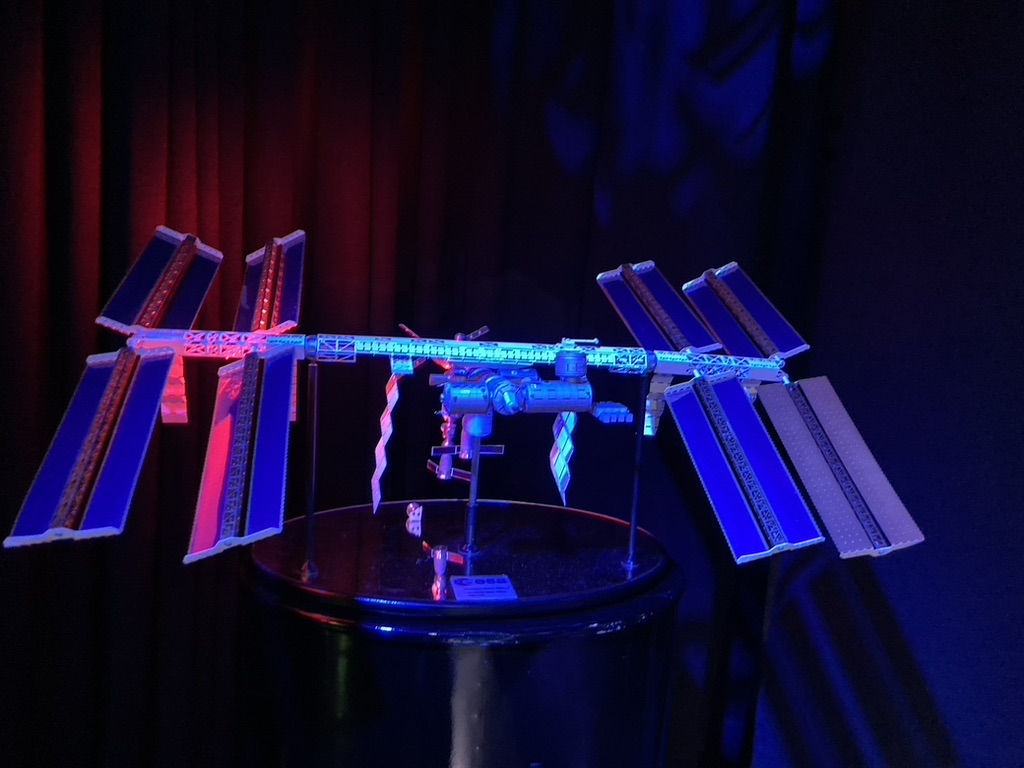

Surrounded by the backdrop of ESTEC’s Erasmus Innovation Centre, a cavernous room filled with space artifacts and replicas, I launched many rockets off to nowhere and with no regrets. It felt especially surreal to engage in such haphazard experimentation given the environment, which was decorated from floor to ceiling with memorabilia of space missions that had actual, tangible stakes. Kerbals may be forgiving, but the same cannot be said for real spaceflight.

As with the original game, you start at the Vehicle Assembly Building of the Kerbal Space Center where you can build spacecraft out of a dizzying variety of parts and send them to the launchpad where they might dramatically explode, sputter out, or maybe—with lots of luck or practice—actually reach an orbit around Kerbin, the Kerbals’ home world, or beyond into the wider Kerbol solar system.

KSP2 has reimagined the familiar worlds from the first game, and will include new features such as the ability to build complex extraterrestrial colonies and even venture out on interstellar voyages to other star systems. The game’s meticulous scientific verisimilitude, its most precious asset, has now been applied to the lofty dreams of multiplanet settlements and voyages to the stars, whereas the first version was confined to the Kerbol system.

“Players who've been playing KSP1 have a whole beautiful new star system to look into,” said Shana Markham, lead designer at Intercept Games, the studio that made KSP2, in an interview with Motherboard at the event. “Every celestial body that I've gone to and visited has been just a completely wild treat.”

“Not only have we rebuilt all of our celestial bodies from the Kerbol system, we also have introduced, on day one of early access, four new tutorials—including tutorial videos and adorable animations—that will help onboard new players and also refresh old familiar players with orbital mechanics and the concepts of space travel and rocketry” such as “building, flying, and crashing,” added K. Ness, the art director for KSP2, in the same interview.

After about an hour of building, flying, and crashing, I took a break from the game to speak with Sara Pastor, an aerospace engineer at the European Space Agency (ESA). We met in an auditorium next to the Erasmus center to talk about her work on the Lunar Gateway, which is a planned space station destined for lunar orbit that will serve as a stepping stone for human exploration of the Moon and, perhaps eventually, Mars. (Building a Kerbal version of the Gateway is something players can do in the game, by the way.)

“This is a small station that will be orbiting around the Moon,” Pastor told me. “The Gateway is used to really prepare for both [exploration of] the Moon’s surface and also excursions to Mars.”

As a collaboration between NASA, ESA, and many other partners, the Gateway is considered a key stepping stone in human space exploration and a major part of the NASA-led Artemis program, which aims to return humans to the lunar surface this decade.

The station is currently on track to launch in about five years, and will follow a highly elliptical orbit that will come within 1,000 miles of the lunar surface at its closest approach, before hurtling out to an unprecedented distance of 43,000 miles at the far end. Unlike the International Space Station, which is continuously inhabited by astronauts, the Gateway will be occupied by crews for short stays, ranging from a few days to a few weeks, and will serve as a staging ground for human expeditions to the Moon’s surface.

As the project manager for the Gateway’s International Habitation Module (I-HAB), a cozy living space on the station, Pastor must anticipate the many challenges of life in a remote lunar outpost. For instance, the team is currently combing through data collected by Artemis 1, an uncrewed test mission that flew around the Moon last year, in order to figure out how to reduce the crews’ exposure to cosmic and solar radiation.

“On Artemis 1, there was a mannequin with a sensor, so we are waiting for the answers and the final report on that so we can see what the bodies of the astronauts experience in that orbital environment,” Pastor said.

Radiation exposure is just one of countless contingencies that Pastor and her colleagues will have to evaluate as they develop the Gateway, and prepare to return humans to the Moon. As I returned to my console after our interview, I realized I would be intimidated just to build a Kerbal version of the Gateway, let alone confronting the challenges of a real orbital outpost.

However, the most avid players of KSP will no doubt relish the opportunity to build space stations, extraterrestrial colonies, and interstellar spacecraft in the forthcoming sequel, which will also have a multiplayer mode. Indeed, the game’s thriving fan community has not only helped to shape the careers of streamers and Youtubers, it has also inspired many players to pursue space science as a profession.

“I think part of the mantle that we are inheriting is the fact that people play this game and then they join the aerospace industry,” Ness said. “This game teaches people orbital mechanics, rocketry, and astrophysics in unexpected ways, so we’re navigating an incredibly enthusiastic community who might be more knowledgeable about these topics than us.”

“This is a game that is interesting because it seems to hit players in many different ways,” Markham noted. “For every player that I've met that has been long-haul-trucking over to Eeloo out onto the edges of the system, I've seen just as many players be just as comfortable making cool rovers or flying planes and doing transcontinental flights on Kerbin. It really sparks a lot of creativity and curiosity in not just aerospace but the surrounding aspects of it.”

Despite all of the kaleidoscopic possibilities within the Kerbal universe, the game’s unifying heart remains the “Kerbonauts” and their oddly reassuring determination in the face of a mind-boggling variety of death traps.

“We try to use Kerbals as a way to soften the harshness of failure,” Ness said. “They're having a good time, no matter what.”