QAnon Isn’t Dead, It’s Growing

February 24, 2022In November 2020, Donald Trump lost the presidential election. In December 2020, the anonymous poster known only as “Q” stopped posting updates, or “Q drops.” In January 2021, in the wake of the Capitol riots, social networks purged their platforms of accounts and groups associated with QAnon.

Many saw these developments as the final nails in the coffin of a conspiracy movement that had briefly consumed millions of Americans who now believed that a group of Satan-worshipping elites from Hollywood and the Democratic Party was operating a child sex-trafficking ring in order to harvest children’s blood. But with Trump’s loss, Q going silent, and access to Twitter and Facebook removed, the reasoning went, the QAnon fever was sure to break.

But the reports of QAnon’s death have been greatly exaggerated. In fact, the number of Americans who say they believe in some or all of the core conspiracy theories pushed by the QAnon movement is now greater than it was a year ago.

That’s according to a new survey from the Public Religion Research Institute, a nonpartisan research group that shared its findings with VICE News before the survey was published on Thursday morning.

The survey found that 16% of Americans believe in the core tenets of the QAnon conspiracy theory, up from 14% a year ago. QAnon believers are deeply distrustful of government and other institutions, the survey found, and believe deeply that there is “a pervasive threat to their culture and way of life.”

While white Republicans are more likely to be QAnon believers, the survey found that the movement is hugely diverse: There are QAnon adherents all over the United States, at all levels of education, and from numerous religions. But the researchers found that far and away the single biggest predictor of belief in QAnon conspiracies is a preference for watching right-wing news outlets, including Newsmax and Fox News.

While other surveys have found belief in QAnon to be much lower than what PRRI’s research indicates, Jackson said this can be explained by how PRRI’s questions were presented.

“With Trump out of power, with Q themselves not being particularly active, we might have expected a dropoff in people believing these things,” Natalie Jackson, director of research at PRRI, told VICE News. “But, the way we phrased the questions intentionally did not mention QAnon. This was so we could capture the people who are willing to believe these really out-there things, but would be tipped off by the word QAnon to know that it’s something that they should back away from.”

In the wake of the Capitol riot last year, where QAnon adherents played a central role, members of the community had already begun to distance themselves from the term “QAnon,” falling back on an old Q post that said: “There is Q, There are Anons. There is no QAnon.”

So to get a better sense of how widespread core QAnon conspiracy theories have become, PRRI’s respondents were asked if they believed in these three core tenets of the movement:

- The government, media, and financial worlds in the U.S. are controlled by a group of Satan-worshipping pedophiles who run a global child sex-trafficking operation.

- There is a storm coming soon that will sweep away the elites in power and restore the rightful leaders.

- Because things have gotten so far off track, true American patriots may have to resort to violence in order to save our country.

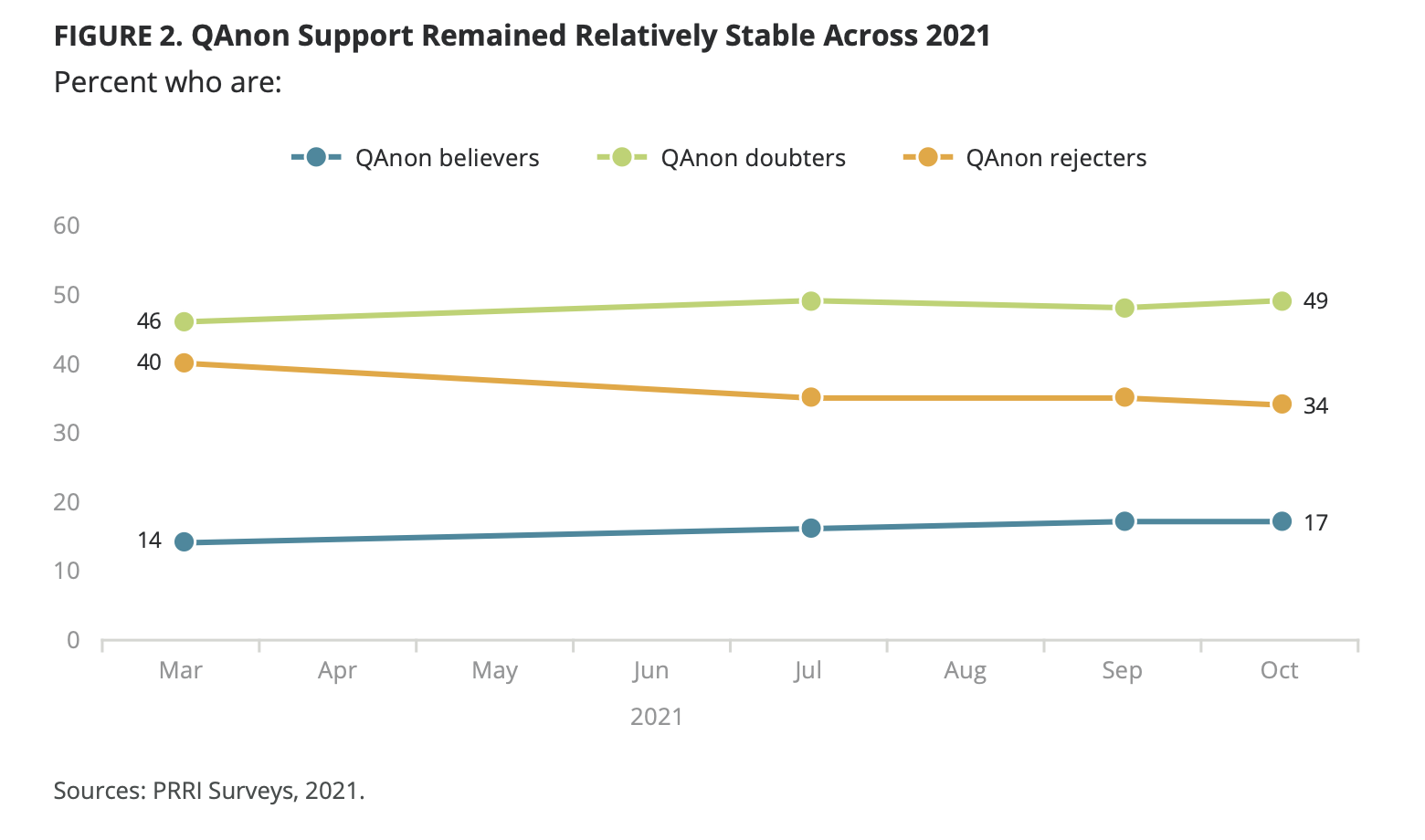

To get an overall picture of how widespread QAnon beliefs are, PRRI created a composite measure from these three questions and identified three distinct groups: QAnon believers, QAnon doubters, and QAnon rejecters.

The survey found that the number of people who mostly or completely agreed with the three statements above (QAnon believers) had actually risen throughout 2021, from 14% of Americans in March, to 16% in July, 17% in September, and 17% in October.

The survey also found that while more Republicans and more Americans without a college education were among the QAnon believer category, the conspiracy movement has indoctrinated people from all backgrounds.

“It’s not all Republicans, it’s not all uneducated folks,” Jackson said. “I think the diversity of who is susceptible to believe these things is somewhat surprising and breaks the myths that are out there about who believes in conspiracy theories.”

But there is one independent indicator above all others that is the best predictor of being a QAnon believer: media consumption.

“Americans who most trust far-right news outlets like One America News Network (OANN) and Newsmax are nearly five times more likely than those who most trust mainstream news to be QAnon believers,” the report states. “Also, Americans who most trust Fox News are about twice as likely as those who trust mainstream news to be QAnon believers.”

These networks are not directly sharing QAnon conspiracy theories or urging their audiences to believe them, but they are playing on one of the key aspects of what believing in QAnon means: mistrust of everything and everyone.

“There is a strong connection between the suspicious mindset and a lack of trust in anything, and the far-right networks really do capitalize on that lack of trust and the fear that the other side is out to get you,” Jackson said. “So even if they’re not directly endorsing the QAnon theories, they are fostering that sense of mistrust.”

The upshot is that despite repeated claims that QAnon was dead or dying, this conspiracy movement has managed to embed itself in American society and will likely influence the outcome of the 2022 election, just as it tried to do in 2020.

According to a tracker maintained by Media Matters for America, there are 54 current or former 2022 congressional candidates who have embraced the conspiracy movement, hoping to follow in the footsteps of Reps. Marjorie Taylor Greene and Lauren Boebert, whose embrace of QAnon didn’t prevent them from winning seats in Congress.

Over the course of the last two years, many QAnon beliefs have become part of Republican Party orthodoxy, none more so than the belief that the 2020 election was stolen, a conspiracy theory that first surfaced in the QAnon fever swamps of 8kun.

2020 was the year QAnon broke out from the fringes of the internet to become a mainstream phenomenon on Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter–supercharged by the pandemic that forced millions to stay at home and spend more time online.

At the beginning of 2021, mainstream social networks finally took decisive action against QAnon groups and accounts, but the damage had already been done. The resulting mass purges of highly influential accounts made little measurable difference, the PRRI report suggests.

“We don’t have any reason to believe that it’s impacted QAnon beliefs much,” Jackson said of the social media purges. “In general, when people want a specific type of information, they’re able to find it, and even when those platforms were taken off of some social media services, they've remained active on other places on the internet.”

While belief in QAnon conspiracy theories has remained steady and even grown slightly in the last 12 months, Jackson doesn’t see it growing exponentially in coming years because “for conspiracy theories that are this out there, this extreme, there is a ceiling on the number of people who will be willing to buy into that.”

But new conspiracy theories could emerge that feed on the sense of distrust and malaise that QAnon has fostered in a huge swathe of American society.

“That general sense of mistrust is where the fertilizer for believing in conspiracy theories comes from,” Jackson said. “Why we see conspiracy theorists everywhere, in every demographic, is that the core of it is a mistrust in institutions and the things around you—and everybody can have that [because] we have a big trust problem in this country right now.”

Want the best of VICE News straight to your inbox? Sign up here.