How a Beheading Triggered a Flood of Sexual Assault Accusations Against Rich Young Men

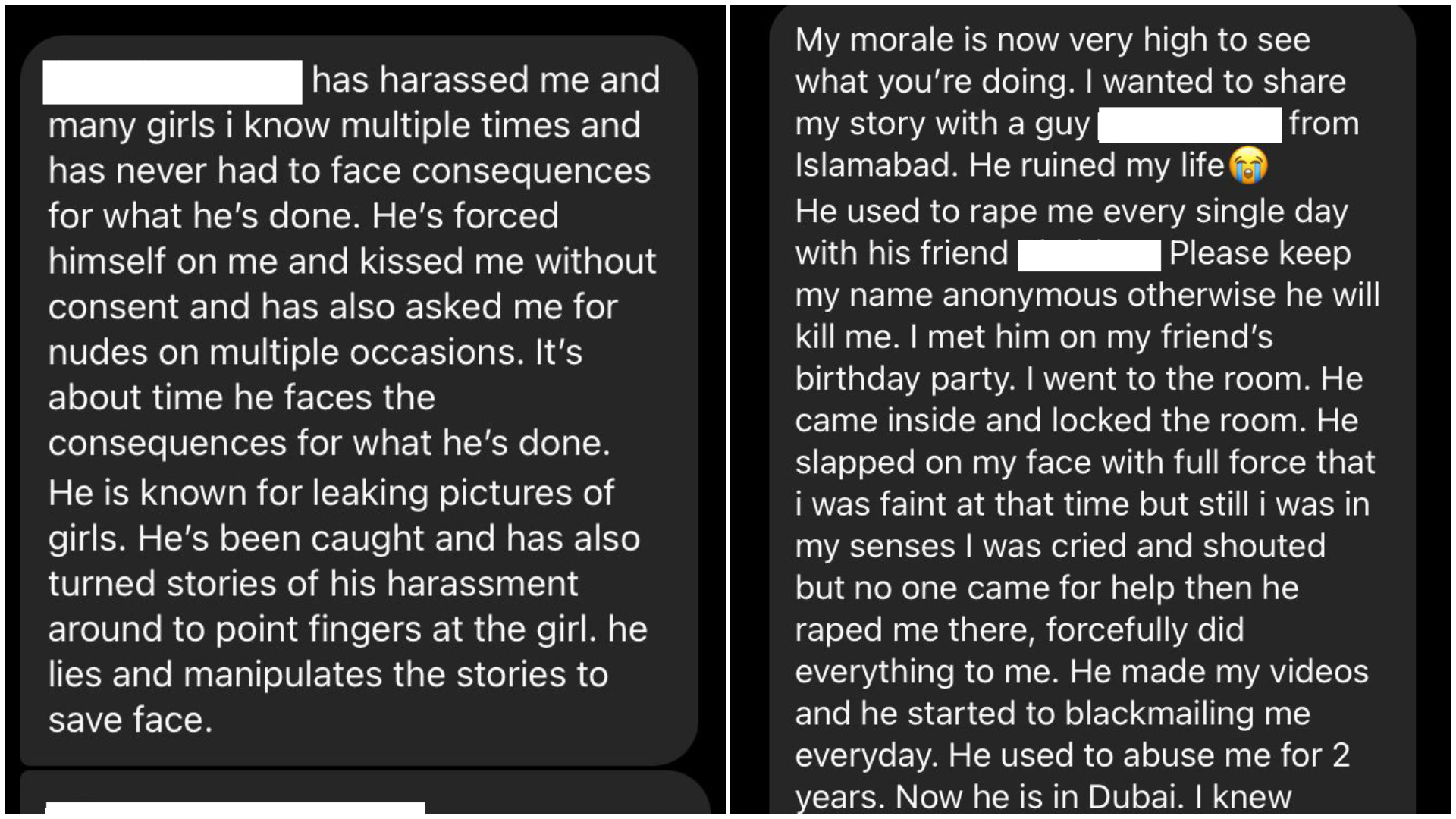

September 14, 2021The harrowing messages landed in her inbox one after another. The messages accused men from Pakistan’s most powerful and wealthy families of sexual misconduct, from harassment to rape.

Zahra Haider, a Pakistani-Canadian activist in Canada, read them with indignation. Then she shared those allegations with her thousands of followers on social media.

What came next amounted to something of a #MeToo moment in the Islamic republic, with accusers converging on the 27-year-old woman’s Instagram page. The accused are sons of the country’s political and business elites, including policymakers and owners of prestigious private schools.

But while similar campaigns elsewhere, from the United States to China, have led to punishments for some of the perpetrators, the allegations of sexual violence in Pakistan have gone nowhere. None of the 400 accusations, against nearly 50 men in the upper echelons of the Pakistani capital of Islamabad, have resulted in police investigations, in part because no accuser has pursued legal action.

The women’s reluctance to come forward speaks to what rights activists say is a climate of fear preventing survivors of sexual abuse from seeking justice.

This fear is unsurprising, they say, given that Pakistan has one of the world’s lowest rape conviction rates—0.3 percent—and its prime minister routinely faults women for how they dress. A TikToker’s recent mass assault by 400 men was called a publicity stunt by many social media users.

And in that climate, hundreds of women turned to Haider. “These women were genuinely afraid of their partners or ex-partners. They’ve been gaslit, they’ve been threatened, they’ve been bullied, they’ve been intimidated,” Haider told VICE World News.

The women who came to Haider have all shared their stories anonymously, seeking not as much justice as to make sure no one else meets the fate of her murdered childhood friend, Noor Mukadam.

Mukadam, an artist and daughter of a former Pakistani diplomat, was beheaded in July allegedly by the scion of a powerful business family. The brutal killing put a spotlight on the pervasive violence against women in Pakistan, which ranks 153 out of 156 countries in the World Economic Forum’s global gender index. The trial of the alleged killer, Zahir Jaffer, a socialite and son of another wealthy family, began on Sept. 8.

“Everybody is shaken from Noor’s murder. Everybody is scared. Parents are scared. Children are scared,” Haider said.

“It is pertinent right now because it is just exposing and showing us how abuse is and always has been so normalized,” she said.

Devastated by Mukadam’s death, Haider took it upon herself to share anonymous accusations of women against powerful men in Islamabad, many of whom she went to school or socialised with before she moved to Canada for college in 2012.

Most of the anonymous accusations alleged horrific instances of beating, rape, and sexual assault, with some taking place while the women were unconscious or heavily intoxicated.

In one allegation, a woman said two men raped her every day. Another accuser said one of the men forced her to have sex with him. In other accounts, some men were accused of engaging in “predatory behavior” involving underage women.

About half of the women faced violence while they were in a relationship with the accused men.

Haider’s posts have been shared across Pakistani social media and have also appeared in local news reports. But the anonymous accounts of violence have not led to law enforcement actions.

“The reason I came out anonymously was because if anyone found out, people are not going to say that the guy is wrong,” said Sehrish, a 26-year-old woman who works at an insurance company. She requested the use of a fake name due to concerns that she could be sued for defamation. “They will straight up blame the girl who is coming out. They will say it was her fault because she had a relationship with this guy and she should have known better.”

Of the 400 accusers who approached Haider, 160 said the abuse came from men who were their intimate partners, some of whom filmed their sexual activity with the women without their knowledge and blackmailed them with the photos and videos. Sehrish was one of them.

The anonymous accounts of abuse are predicated on Pakistan’s pervasive culture of silence when it comes to reporting sexual violence and harassment.

Accusers are often hit with defamation suits and their alleged abusers are rarely tried in court.

“Most defamation cases that I had heard about the parties somehow find a way to work it out and the survivors have to sign a nondisclosure agreement,” said Leena Ghani, an artist who accused pop singer Ali Zafar of sexual harassment and was charged with defamation along with eight other accusers, including singer Meesha Shafi.

“They can’t really talk about their trauma and they can’t really speak about what happened to them and it’s really unfair and the abusers have all the power. So it’s a way of silencing them,” Ghani said.

Zafar denied all accusations of misconduct. The defamation case against singer Shafi, Ghani and others is still underway. Earlier this year, Ghani filed a counter defamation suit against Zafar after facing online abuse and threats from his supporters.

The majority of the anonymous accusers who messaged Haider come from the same elite social circles as the accused, but they are fearful of a backlash if their identities are revealed.

Zenia, a student in her 20s who contacted Haider, accused pop musician Abdullah Qureshi of sending her unsolicited propositions to engage in BDSM and cater to his foot fetish while she was still a minor. Zenia, who also requested the use of a pseudonym to avoid legal ramifications, told VICE World News that Qureshi manipulated her into non-consensual sexual activity when she was less than 18.

“Consent happens between two adults,” Zenia said. “There was no use of physical force but there was obviously a sense of grooming.”

Through Haider, five more people accused Qureshi of online sexual harassment. Some claimed that Qureshi’s social media messages were aimed at teenagers.

Qureshi publicly apologized through Haider on July 30 for “messaging randoms,” saying he is a “changed man” after the birth of his daughter. He did not address any specific accusations in his statement. Qureshi did not respond to VICE World News’ requests for comment.

“I apologise to everyone for all this. I won't blame my drunken state because it was me at the end of the day. But yes, I did have a drinking problem and I do have fetishes. But everyone has fetishes.”

Zenia said, “He’s responsible for the trauma that he has put so many people through. There is more accountability that needs to take place than what has happened.”

Qureshi has not been charged with any offenses.

Haider’s posts have gained significant traction on social media, where since July her 3,000-strong following has grown to 18,900, and inspired other accounts to share allegations of abuse.

“The use of online spaces by survivors of abuse and harassment is not only cathartic for survivors who are often living with the trauma,” said Usama Khilji, director of digital rights advocacy group Bolo Bhi.

“It is also an important alert for other women who may fall victim to abusers as well as for those who have suffered similar abuse,” Khilji said.

But Haider's campaign has brought her online threats of violence, intimidation and at least one civil defamation lawsuit. New social media accounts, such as Not All Men PK or Against False Allegations, have also emerged to challenge Haider's campaign.

The defamation suit was filed by Pakistani businessman Maher Aziz, who has been accused of physical violence and harassment by five women in stories shared on Haider’s Instagram account. Haider’s posts have also accused Aziz of belonging to the same social circle as Jaffer, the alleged murderer of Mukadam.

The defamation notice served to Haider says her online campaign against Aziz was launched “without ascertaining the truthfulness of the said matter, due to which [Aziz] suffered from mental torture and the loss of reputation.” Aziz demands an apology and compensation of $1.2 million for damages.

Nighat Dad, lawyer and founder of the Digital Rights Foundation, said defamation has emerged as a major deterrent when it comes to the #MeToo movement in Pakistan.

“The fact that defamation is criminalised means that survivors can be slapped with criminal charges for bringing forth an allegation against someone,” Dad said.

“Defamation laws have been weaponized by abusers to intimidate victims into silence and have resulted in many retracting their allegation in order to avoid legal action.”

Despite Sehrish anonymously accusing her abuser through Haider, she continues to worry about retaliation. “Considering that he has a political family background I wanted to stay anonymous. I wouldn’t want to go through with it publicly because of what they could do. His family is very strong,” she said.

Follow Rimal Farrukh on Twitter.