Japan’s Paradise Island is Rife With Poverty

September 10, 2021On this island they call Japan’s paradise, the sea marks the passage of time.

Languid waves beckon to families as they watch the ocean lapping on the ivory beach, its fine sand shifting under the weight of playing children. The high tide sends people home—tall waves hamper the day’s fun. Even then, a patient few wait for the tide’s retreat, drawn in by its cobalt ripples.

But just as the ocean surrounds life here in Okinawa, so does poverty.

Behind its label as the “paradise” of Japan, Okinawa bears the highest rate of poverty in the nation. It’s borne this paradoxical identity for decades, making locals worry that it’s now a part of Okinawa’s cultural identity. It may not be as obvious as derelict houses lining unpaved roads, but poverty has permeated all facets of life here, like sand after a day spent at the beach.

Kana Tsuyama, who has a 5-year-old daughter, is a single mother in Okinawa. She is one of thousands of women here raising their children alone—the prefecture of 1.5 million residents ranks first in single motherhood.

Tsuyama doesn’t think she could survive if it weren’t for her second job as a club hostess. “Many people in Okinawa live paycheck to paycheck. The money I make in one day goes directly to my kid’s schooling, or things for our daily lives. I don’t make enough at my day job to support us,” she told VICE World News.

In Japan, poverty plagues nearly half of all single-parent households, of which 87 percent are supported by single mothers. In Okinawa, this issue is compounded by the alarmingly high rate of child poverty—about 30 percent, nearly double the national average. Tsuyama herself experienced times of poverty before moving back in with her parents.

According to Kotaro Higuchi, a professor from Okinawa University who studies poverty and economics in the prefecture, high rates of poverty among young single mothers means many of them turn to sex work, a convenient and lucrative way to pay bills. Women who left school to have families “won’t have the qualifications necessary to work an office job and therefore can’t secure full-time employment. So they’ll be juggling housework and working until 2 a.m., which is overwhelming for any single individual, and can lead to children being neglected,” he told VICE World News.

Tsuyama reckoned about 60 percent of her single mother friends worked as club hostesses, one of many jobs in Okinawa’s sex industry. “I always have friends approaching me saying, ‘Oh, I’m single now,’ or ‘I’m getting divorced soon, so please tell me where I could find work as a hostess,’” she said. In Japan, hostesses keep customers company by pouring them drinks while sitting and chatting with them.

But against the backdrop of higher poverty rates in Okinawa lies the prefecture’s complex relations with the rest of Japan and its long history of foreign occupation.

Okinawa, once an independent country ruled by the Ryukyu Kingdom, was annexed by Japan in 1879 and reduced to a prefecture. During World War II, the prefecture played a key part in the United States’ planned occupation of Japan, and was ravaged by the fighting. An estimated 200,000 civilians were killed during the Battle of Okinawa, one of the bloodiest land battles in the Pacific War.

After the war, the U.S. occupied Okinawa until 1972, when it was returned to Japan. The heavy influence of American culture, from the 28-year occupation to the presence of large U.S. marine corps bases today, made it difficult for Okinawans to reassimilate into Japanese society, said Yuko Irie, a native Okinawan and assistant professor who studies child poverty at Tokyo Gakugei University.

“Okinawa was returning to Japan after the country had experienced great economic growth in the 60s. They had to play catch up with many societal ‘givens,’ like its education and employment system, and the way many employees stayed at one company for a long time,” she told VICE World News. Okinawa’s physical distance from the rest of Japan also made trade more difficult and expensive, Irie added.

Japan’s oil crisis in 1973 caused a spike in unemployment rates across the country, and as a result, Okinawa struggled to find its economic footing. Higuchi said poverty was no longer merely an economic issue, but one that affected the psychological and physical health of individuals in the prefecture. In 2018, Okinawa had the highest suicide rate in the country, he pointed out.

Alcoholism and deaths related to intoxication are other societal issues linked to poverty in Okinawa. In 2017, the prefecture had the highest mortality rate caused by alcohol-related liver disease among both women and men.

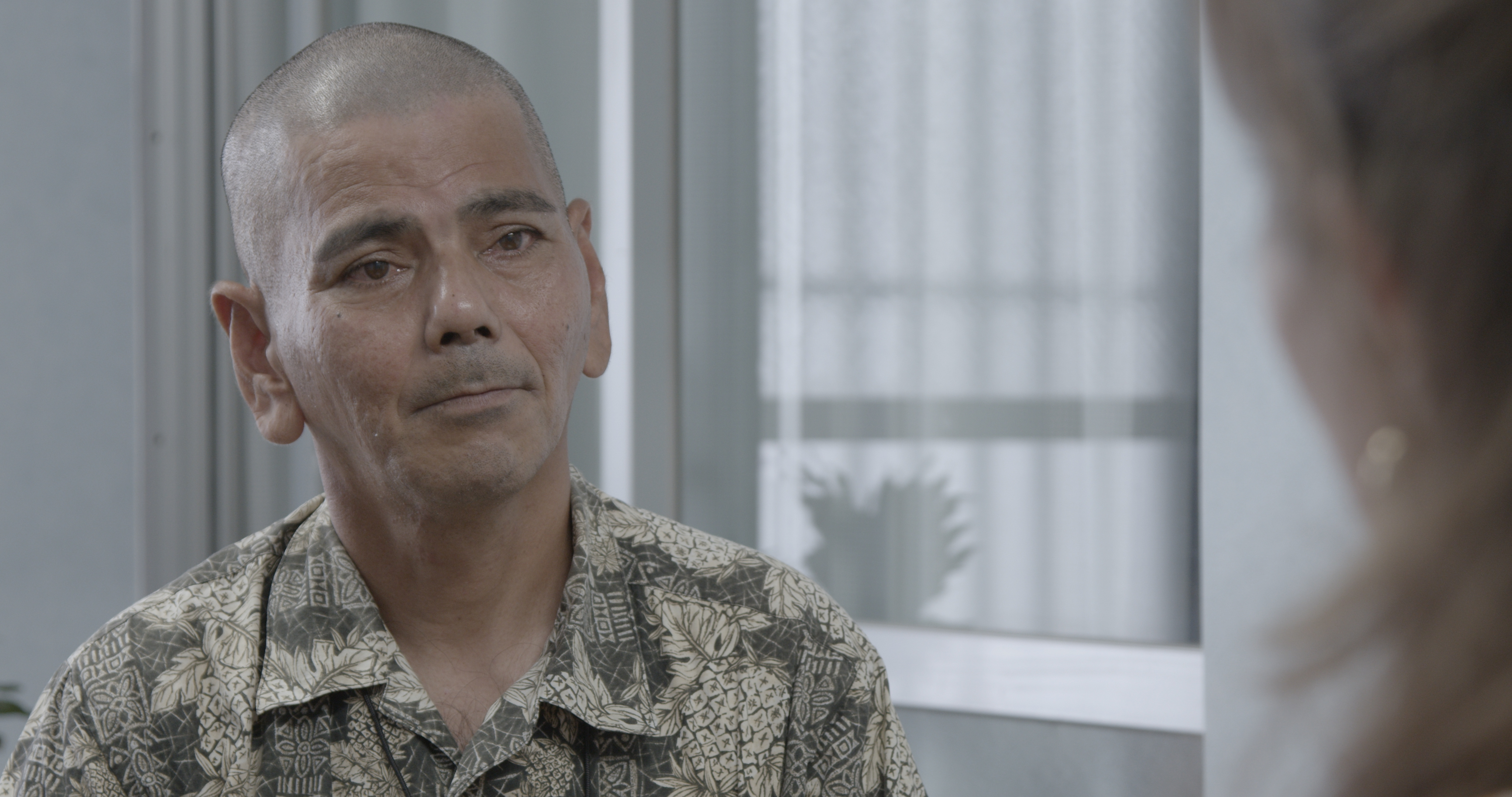

Teruyuki Fukumoto, who has struggled with alcoholism since the age of 18, said he first developed alcohol dependency when he started working at izakaya (Japanese bars) in his 20s. Encouraged by customers to drink, Fukumoto soon found himself drinking throughout the day.

“My relationship with alcohol got to a point where I’d start drinking in the morning. I’d skip work, or even if I showed up, I couldn’t stop drinking. My boss would issue warnings, but I couldn’t stop. I was fired, then homeless. I stole alcohol to keep drinking, and was sent to prison for that. I’ve been in and out of prison five times now,” he told VICE World News.

Scholars worry that poverty’s effects are cyclical and can transcend generations. Meanwhile, the Okinawan prefectural government has initiated steps to eradicate poverty.

The prefecture has established a consultation center and a welfare fund loaning system to assist locals in financial trouble. It also relaxed rules on loan requirements and extended payment deadlines to encourage people to seek financial support.

“Those who are really struggling financially aren’t worried about tomorrow’s money; they have to think about today,” Okinawa Governor Denny Tamaki told VICE World News.

But for Tsuyama, borrowing money isn’t the issue. It’s the psychological effects of her work-life balance—or the lack thereof—on her daughter that bothers her.

“I’m worried about her emotional stability in the future. When I leave at night, she cries and begs me not to go,” she said. “But I promise her that I’ll always come home. And when I do, I bring her a lot of money and show her, ‘See! Look how much money Mommy made for you.’”

She’s not ashamed of her work as a club hostess, Tsuyama said, but she doesn’t want her daughter to live the same life, where each decision she makes is marred by stress and sheer practicality.

Instead, she wants her to protect her childlike glee—the same glee with which she cries out as she runs across the beaches that convinced visitors to call the island paradise.