Andrew Brown Jr.: Why Bodycam Video of His Death Is Still Secret

May 3, 2021Want the best of VICE News straight to your inbox? Sign up here.

Andrew Brown Jr.’s family has to bury him Monday without knowing exactly why he was killed by law enforcement 12 days ago. That’s because an unusual law in North Carolina prevents body camera footage from being released without the approval of a judge.

“I’ve done these cases all across the country. This is the weirdest situation I’ve ever been in. I don’t know why the law was written this poorly,” said Bakari Sellers, an attorney for Brown’s family and former South Carolina Democratic lawmaker.

In 2016, North Carolina passed the law—with bipartisan support—that forces people to obtain a court order before law enforcement can release body camera and dash camera footage. The intent was to create a neutral arbiter to balance victims’ and the public’s right for transparency with concerns from police. But law enforcement experts say the piece of legislation—the only one of its kind in the country—needs to be reformed.

“The current law is creating more problems than it’s solving,” North Carolina Democratic state Rep. Amos Quick told VICE News. “We see with all these obstacles that have been put in place there’s no transparency at all. It’s bred suspicions that authorities are hiding something and that some nefarious things are going on.”

So far, Brown’s family has seen only 20 seconds of footage from the unarmed 42-year-old Black man’s death, which they’re calling an “execution.” But six videos of Brown’s death exist—five from deputies’ body cameras and one from a law enforcement vehicle’s dash cam—and the Pasquotank County Sheriff has said he wants to release them all to the public.

Last week, a judge ruled he can’t for at least 30 days, "to allow completion of any investigation being undertaken.” The judge will let Brown’s family see more of the footage by the end of this week—but with only one of their attorneys present.

On April 21, Pasquotank County sheriff’s deputies attempted to execute a search warrant and arrest on Brown for alleged drug possession. According to attorneys for Brown’s family, they began firing before they reached the car, and Brown had both of his hands on the wheel of his car and wasn’t making any sudden movements before police shot him five times, once in the back of the head. His family says he didn’t attempt to drive off until he’d already been shot at.

County officials dispute that—District Attorney R. Andrew Womble has said that police didn’t start firing until Brown struck officers with his car while attempting to flee.

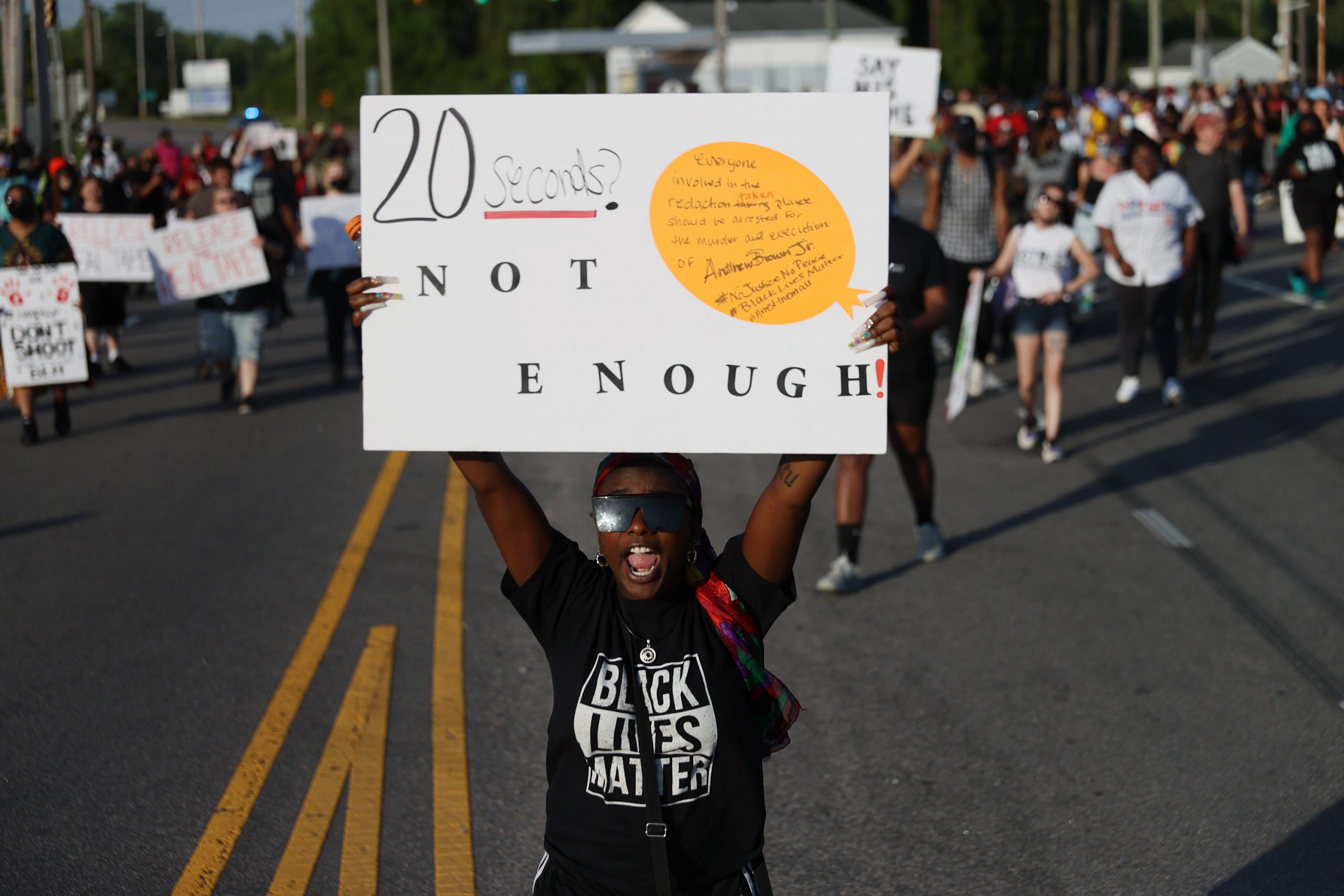

The lack of transparency has heightened tensions and led to accusations that the police are intentionally hiding what happened. Protesters in Elizabeth City, a small Black-majority city in eastern North Carolina, and across the state have taken up “release the tapes” as a rallying chant. Officials responded with a curfew and requirements that organizations get permits to protest.

“North Carolina is very strict about releasing body-worn camera footage,” said Daniel Lawrence, a policing technology expert at the Urban Institute's Justice Policy Center.

“I don’t know of any other states that have the requirement of a judge order to release body-worn camera footage. In most instances, it’s left to the law enforcement agency and can be superseded by the district attorney’s office.”

The current law was passed in 2016 during a statewide surge in use of police body and dashboard cameras—and just one week after the Charlotte-Mecklenburg Police Department finally released the footage of police killing Keith Lamont Scott, a death that set off widespread outrage and protests in the city.

“This is the weirdest situation I’ve ever been in. I don’t know why the law was written this poorly.”

At the time, North Carolina didn’t have any specific law governing whether police departments had to release bodycam footage or not and was silent on whether bodycam footage counted as a public record or a considered personnel records, which would be privileged and not allowed to be publicly accessed. That basically left each department to decide whether or not to release the materials.

Republicans also had unified control of North Carolina’s government and crafted a solution they thought would balance the public’s right to know concerns about both police and victims’ privacy as well as protecting evidence in possible pending cases.

“The key I think in the whole legislation is to find the person who’s neutral, not part of any side of the event, is just a decisionmaker for the process, and that’s what the judges were put in there for,” North Carolina GOP state Rep. John Faircloth, a retired policeman who was the law’s chief sponsor in the assembly, told VICE News.

Democrats say they were given some chance to weigh in on the laws’ details in a bipartisan attempt to craft good legislation. And while many had qualms that the bill was too onerous a process to get videos released, most Democrats saw it as an imperfect improvement over the status quo and voted in favor.

“We had no law on the books so citizens had no right for obtaining video. We wanted to get something on the books with the intent of revisiting it later,” said North Carolina Democratic state Sen. Ben Clark, who voted for the law in 2016 and is a lead sponsor on the reform bill Democrats are now backing. “I thought all along having to have citizens go to court for videos wasn’t best but in legislatures you had to compromise at times.”

Not everyone agreed.

State Sen. Jeff Jackson was one of two Democrats to vote against it, and told VICE News the Brown case has proven he was right.

“We were told at the time that they knew it was imperfect and they’d come back to it and I just didn’t trust them to do that,” he said. “It clearly overly restricted the public’s access to bodycam footage.”

The reform bill was filed weeks before Brown was killed but has received renewed attention in the wake of his death. North Carolina Democratic Gov. Roy Cooper announced his support for the reform this week.

The ruling to block the footage surprised even some proponents of the law. North Carolina judges have in past cases regularly granted reporters and other requesters’ access to footage of police shootings.

“This is the first blow-up. It [the law] had been working well, the press has been able to get things when they needed, and we haven’t had anything like this since it was enacted,” said University of North Carolina law and government professor Frayda Bluestein, who was an informal adviser in crafting the law in 2016. “I really don’t understand how this went awry.”

It’s not even clear whether the ruling can be appealed. Sellers, one of the Brown family’s lawyers, told VICE News that they’re asking for clarification on a point of law. Others, including some of the law’s original sponsors, couldn’t tell VICE News whether there was a clear legal process to appeal a ruling.

But the law has proven more onerous than some other advocates expected, and the Brown case has gone further in convincing Democrats that things must change so that North Carolina’s Black community and others can trust that they’ll be able to see what really happened.

There’s no sign Republicans are ready to sign on to any reforms, however. And given their large majorities in the state legislature, that means the law is likely to stand as is barring a sea change in public opinion and GOP views.

“I still support the law as written,” said Faircloth, the current law’s author.

Faircloth declined to say why he opposed putting the onus on police and sheriffs’ departments rather than citizens to argue why footage shouldn’t be released, but argued that it was important to have judges involved as a neutral arbiter.

And time is running short to change the law. The North Carolina Legislature is only in session through early June, and without significant GOP support the bill won’t be considered again until the next biennium—the two-year legislative cycle—once this session ends.

“If they want to do it we can get it done now,” said Clark, the reform bill’s sponsor. “If they don’t want to get it done, it’s not going to happen—in this biennium or the next.”