“They Started Burning the Homes”: Ethiopians Say Their Towns Are Being Razed In Ethnic Cleansing Campaign

February 27, 2021“They set our crops on fire, then they started burning the homes,” said Gebru Habtom, a farmer in his 40s from the village of Debre Harmaz in Ethiopia. “Then they said they’d burn me next, so I fled for my life.”

Gebru, whose name has been changed to protect him from reprisals, was born and raised in the village of Debre Harmaz in central Tigray, some five miles from Ethiopia’s border with Eritrea. Like thousands of others, he has been displaced by Ethiopia’s months-long civil war.

Gebru connected with VICE World News from an undisclosed location along the Ethiopian-Sudanese border, and said that there was no sign of war or even resistance fighters present when, on January 10, Eritrean soldiers arrived in his village and went on a murderous rampage, pillaging and setting homes alight. “They shot at everyone, they even killed priests who were hiding in the church,” he said. Gebru also said that he heard about neighboring villages experiencing similar destruction that has also gone unreported.

“They shot at everyone, they even killed priests who were hiding in the church.”

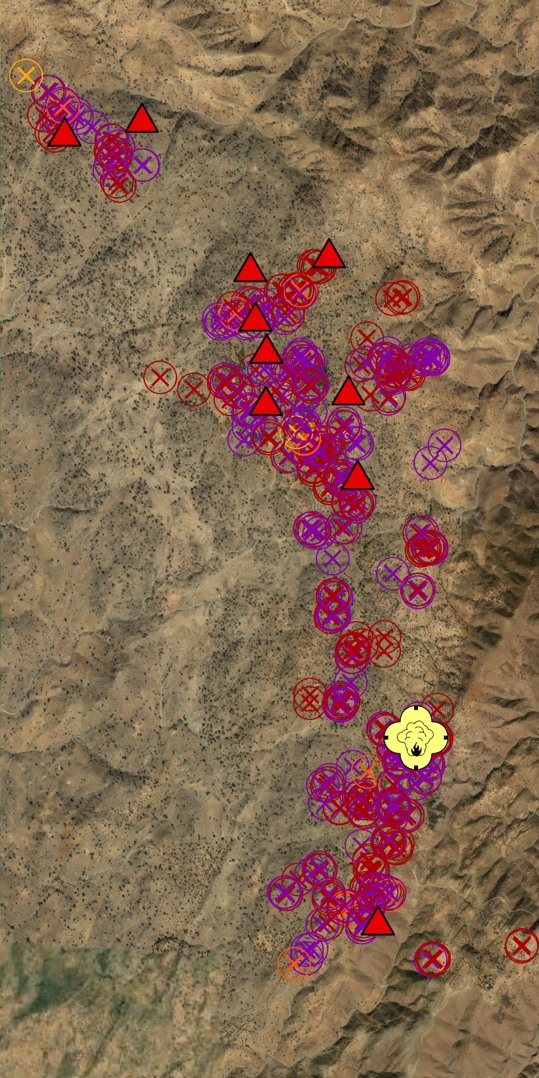

Over the past month, VICE World News has documented harrowing testimony from nine displaced Tigrayans who recalled wanton slaughter, the destruction of crops and livelihoods, and tens of thousands fleeing from areas of Ethiopia’s Tigray region under Eritrean military control. Their testimony has been largely confirmed by satellite image analysis by the U.K.-based research organization DX Open Network, and their recounting and the image analysis both suggest that Eritrean soldiers involved in Ethiopia’s war in Tigray are ethnically cleansing communities near the Ethiopian-Eritrean border.

While several towns in the area have been previously reported destroyed, VICE World News found that, at minimum, an additional four villages in Tigray have likely been razed, and their inhabitants killed.

Eritrean soldiers first entered Ethiopia’s civil war to fight alongside the Ethiopian army against forces of Tigrayan People’s Liberation Front, known as TPLF, or the governing party in the region. In November, soldiers from the two countries succeeded in jointly pushing out Tigrayan forces from the regional capital, Mekelle, and have been accused by international organizations like Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch of brutal war crimes and indiscriminate shelling that targeted civilians and is believed to have left thousands dead.

Residents say that though Ethiopian prime minister Abiy Ahmed declared victory and the end of combat operations, Eritrean military units have continued attacking civilian areas, looting and killing before setting properties ablaze to render entire areas uninhabitable.

Now, Ethiopia claims it is conducting clean-up operations across parts of rural Tigray. Satellite imagery from central Tigray’s Eritrean border, however, points to something far more nefarious.

Like Debre Harmaz, the remote farming community of Adi Mendi, located three miles from Ethiopia’s border, also appears to have been destroyed. According to analysis by the DX Open Network, satellite imagery revealed that on January 19, some 478 structures, mostly tukul homes made from compressed straw, grass and mud, were set on fire. Tukul homes are common in farming communities across Ethiopia.

“Many of them were burnt alive in their homes.”

“Absence of scorching between blackened structures suggests intentional burning, not the result of a wildfire,” the DX Open Network said of the images in a statement to VICE World News. “Perpetrators likely went from structure to structure to initiate razing. And furthermore, there were no apparent indicators of any militarily valid targets.”

“Many of them were burnt alive in their homes,” said Adamu Gidey, who hails from the nearby town of Rama and is well acquainted with the border areas. “I’ve met with survivors, who told me that the Adi Mendi is now a ghost town. Farmers were forced by Eritrean soldiers to slaughter their cows and prepare food for the soldiers. They later doused the homes of these same farmers in gasoline. Adi Mendi no longer exists.”

The satellite images of the visible scorched aftermath point to possibly thousands of people being rendered homeless or far worse.

“The people of Adi Mendi were farmers who would go once a month on hours-long treks to nearby areas to sell their produce, as there are no paved roads for vehicles,” said Gidey, whose name has been changed to protect his safety. “They didn’t deserve this cruelty.”

The DX Open Network’s analysis also confirmed that in recent weeks, the razing has begun to expand beyond central Tigray. The village of Ademeyti, located just south of the long contested town of Badme, and flashpoint of the 1998-2000 Ethiopian-Eritrean border war, was similarly ransacked, with homes set on fire as recently as February 16. DX Open Network shared satellite imagery of Ademeyti’s ruins with VICE World News.

While much of the war was fought under a communications blackout, as phone and internet services were severed from the entire area and aid workers and journalists were not allowed into the region, multiple reports this past week have echoed similar findings of ethnic cleansing and indiscriminate destruction. Yesterday, the New York Times published portions of a U.S. government report which stated that ethnic cleansing was rampant in northern Tigray. According to the report, “whole villages were severely damaged or completely erased.”

According to an Amnesty International report also published on Friday, Eritrean soldiers killed hundreds of civilians in the Tigrayan city of Axum from November 28 through November 29 in one of the worst atrocities of the war. Going door to door in the city’s residential areas, soldiers singled out males of fighting age and murdered them in their homes, the report stated.

Ethiopian soldiers are also accused of involvement in mass killings and are believed to have played a role in the systemic razing of two UNHCR run refugee camps.

For months, Ethiopia and Eritrea had denied reports that Eritrean soldiers were involved in Ethiopia’s civil war. But footage uploaded to the internet and credible reports of their involvement in atrocities led to U.S. officials calling on Eritrea to withdraw its forces. Refugees told VICE World News that they believed that Eritrea’s territorial control in Ethiopia likely extended beyond Tigray’s Maekelay district. The U.N. has echoed these concerns; chief coordinator of humanitarian efforts Mark Lowcock recently stated his belief that Ethiopian troops only controlled between 60% to 80% of Tigray, and that Eritrean soldiers operating in the area control much of the remaining areas, pursuing their own objectives independent of Ethiopian command.

“They aren’t just crossing the border, they are in control of the entire area.”

In February, on a panel organized by German news outlet Deutsche Welle, Ethiopia’s Foreign Ministry spokesperson Dina Mufti conceded that Eritrean soldiers “might have crossed into porous border areas to contain lawlessness.”

But refugees from the same border areas refute this. “They aren’t just crossing the border, they are in control of the entire area,” says Girmay, who requested he be referred to only by his first name to protect his safety.

Girmay fled his family’s farm located in a village in the Maekelay district’s border areas after getting word that Eritrean soldiers were advancing on it. “Since the war started, we haven’t seen a single Ethiopian soldier. Only Eritreans,” he told VICE World News. “They occupy the rural areas.”

According to Girmay and four others who fled the region, the Eritrean state-run telecommunications provider Eri Tel’s network’s reach was expanded into Maekelay, meaning that unlike inhabitants of other parts of Tigray, left in the dark by the Ethiopian government’s communications shutdown, residents of the Maekelay district have been able to maintain their phone service, using Eritrean sim cards. Eritrean soldiers started to sell them, they said, after realizing the high demand.

“It’s as if we’re no longer part of Ethiopia,” he explained. “People calling you with numbers that have the +291 instead of the +251 area code, Eritrean soldiers in control of the area. But at least using the Eritrean numbers, we can warn our friends when there’s danger.”

The sudden expansion of Eritrea’s cellular network into parts of Eritrean occupied Ethiopia points is worrying, said Girmay. But he also believed it helped save lives, including his own.

Girmay says the tiny and mountainous Ethiopian village of Adi Fitaw, located two miles from the Eritrean border, was attacked twice by Eritrean raiding parties; first in mid-December and later on January 11. He told VICE World News that he fled his own home, located in a nearby village, after being warned over the phone of the second attack.

After VICE World News asked researchers from DX Open Network about this purported attack on Adi Fitaw, the organization’s researchers obtained satellite imagery from the town which they analyzed and found that approximately a dozen homes in the village were destroyed in fire-based attacks that occurred prior to January 5.

“Like the many similar attacks in rural communities, there are no apparent indicators of militarily valid targets in Adi Fitaw and there are clear indicators of the deliberate burning of homes there,” DX Open Network said.

Betre Gebreselassie hails from May Wedenberai, another village near Adi Fitaw, and currently lives in Melbourne, Australia. “Since the Eritrean phone reception started working, I’ve learned that Eritrean soldiers burnt my aunt’s home down,” he told VICE World News. “My aunt and her neighbors were lucky to escape alive. They spent weeks sleeping under trees with almost no food.”

“Like the many similar attacks in rural communities, there are no apparent indicators of militarily valid targets in Adi Fitaw and there are clear indicators of the deliberate burning of homes there.”

His family, he said, also told of other similar stories in the region. “I know of a family of parents and two children who were burnt alive in their home,” added Gebreselassie. “They enter a home, take what they like and then burn it down. They are using camels to cart off stolen possessions.”

Betre and Girmay both said that the extent of the Maekelay district’s destroyed infrastructure and deaths is unknown, but shared the names of at least a dozen separate villages which they say were razed to the ground by the Eritrean military in a manner similar to what happened at Adi Mendi.

“The Adi Mengedi, Adi Berbere, and Haftom villages were all attacked. We’ve also learned of at least 25 deaths on January 1 at Bihiza,” Girmay said. “They burnt homes and took all the cattle, camels and food as loot.”

Neither the Ethiopian Prime Minister’s press secretary, Billene Seyoum, nor Eritrean Minister of Information Yemane Gebremeskel responded to emails sent by VICE World News seeking comment on the findings. Both governments typically rebuff such allegations, with Yemane Gebremeskel only yesterday labeling Amnesty International’s report alleging Eritrean military involvement in the Axum massacre as “fallacious.”

Most of the survivors reached by VICE World News are suffering from trauma and shock, and don’t know if they will have a home to return to once the war is over.

“I think they want to kill us all,” said Samuel, whose name has been changed and who says he witnessed soldiers shoot dead his parents, three of his neighbors, and a young child. “I don't think it would be safe to return, even if things became peaceful. They'd want to finish what they started.”

“I think they want to kill us all.”

The situation looks increasingly grim. The Ethiopian and Eritrean governments refuse to acknowledge abuses by their forces, and preventative measures don’t appear forthcoming. International pressure is also limited: While other governments have made statements condemning nearby attacks, very little has changed.

Hirut Zeray, one of over 50,000 Ethiopians to flee into Sudan, agreed. “Sudan is my country now,” she told VICE World News. “I am safe here and the people are helping us with what little they have. But in Ethiopia, we are treated worse than animals.”