What It’s Like to Go ‘Home’ to a Country You’ve Never Visited

February 15, 2021My mum is from Dominica and my dad from Nigeria. When I tell people that I haven’t yet been to either country, I usually receive a puzzled look. And I can almost always guess the question that comes next: “How come you’ve never visited?”

Honestly? My parents have lived in the UK for over 50 years, and we’ve since lost ties with family in both countries. When I do visit, I’ll technically be going as a tourist.

I’m far from the only millennial in the African and Caribbean diaspora not to have visited the country my parents are from. Twenty-two-year-old Monet is Nigerian and St. Lucian, and has not been to either country.

“I definitely have plans to visit eventually, but I feel in touch with my culture in my own way,” she says. “I’m a Black British citizen with a Nigerian and St. Lucian background. That’s a lot of cultures for one person. My differences don’t make me feel any less Nigerian or St. Lucian.”

Monet adds: “My parents don’t really make much of an effort to go to their home countries. The flight prices for POC countries are also so expensive, a lot of the time it's £1,000 just for the flight.”

Fatima, 23, hasn’t visited her “home” country of Somalia, either. Her parents were born and raised in London, and consider the UK home. “I do have the desire to visit home at some point,” she says. “But I don’t want to overthink it, because what if I don’t end up feeling at ‘home’ once I go? Especially because I don’t know the language. I’m scared I won’t feel that connection I’m yearning for and lacking.”

Fatima’s parents fled Somalia due to war and while her father has told her stories, she knows that there is an “underlying trauma” in them. “And my mum’s own attitude to the country kind of put me off seeing it as a welcoming place to visit,” she adds.

For second-generation people like Fatima and Monet, the subject of identity can be tricky. Their parents came to the UK in search of a new life, and had to integrate in order to avoid discrimination and create the best opportunities for their family. But many millennials whose parents migrated to the UK from Africa and the Caribbean have a very different view. The recent rise of the Black Lives Matter movement and countless incidents of societal racism before it has bred distrust in British institutions, as well as a curiosity and appreciation of our heritage.

Morenike, 20, lives in Ireland and visited Nigeria for the first time in 2019. “My trip to Nigeria, Lagos was a planned family holiday,” she says. “I'd wanted to go for a while but I wouldn't have been able to afford my own expenses or ticket at the time.”

She remembers some of her first impressions of the country: “There were so many people everywhere – and they were all Black. From living in Ireland, that was not something I was used to at all. Our first meal in Nigeria was spectacular, we ate amala, gbegiri and ewedu. I fell in love with the food and was so happy to be home.”

Like Morenike, 29-year-old Dammy also visited Nigeria for the first time in 2019. “I felt like an outsider in public because the locals sensed we weren’t from there,” he recalls. “We went to a big market in Lagos and people came up to us trying to sell us food, drink and electronics.”

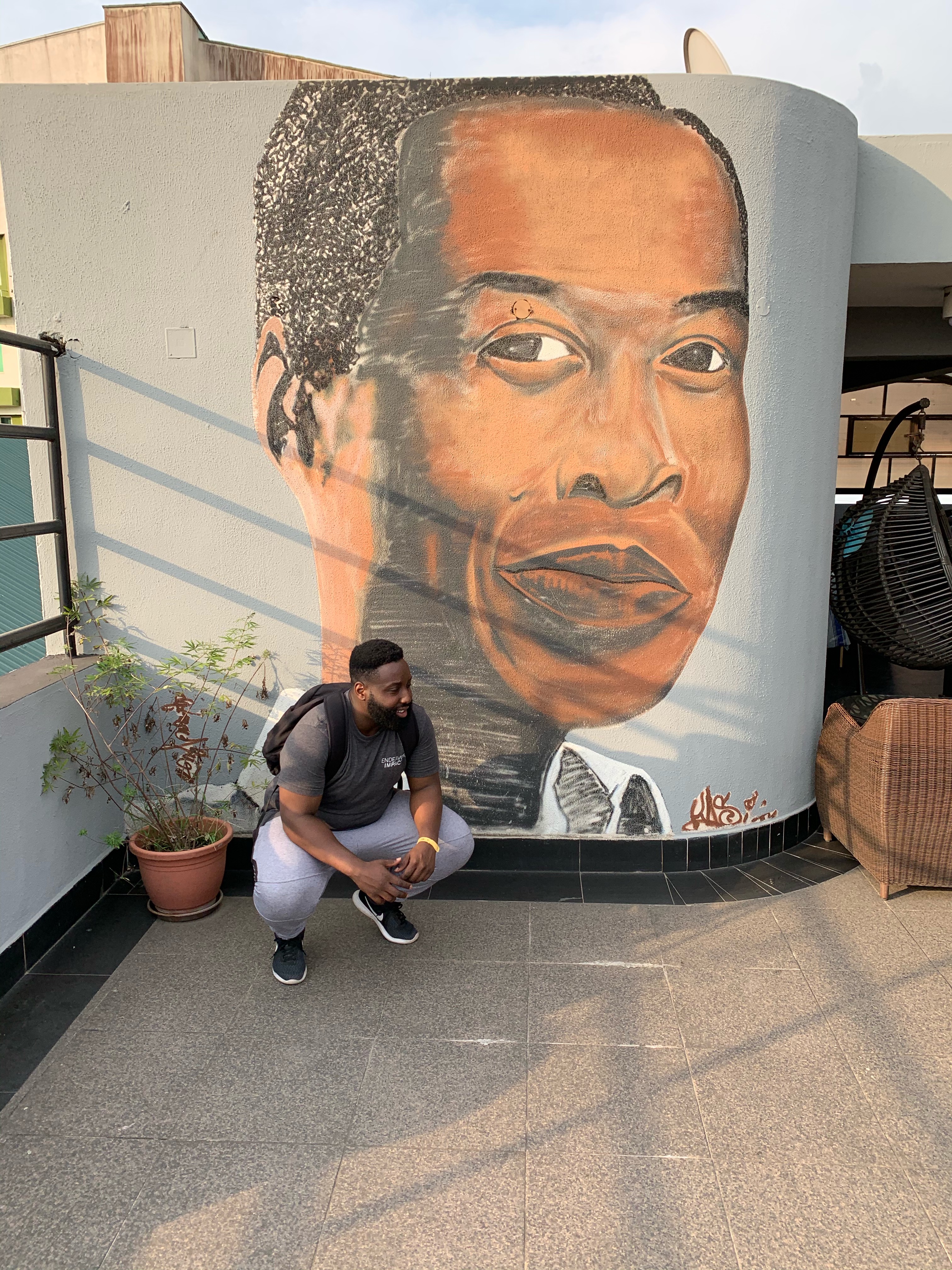

As well as the market, Dammy visited the shrine to legendary Nigerian musician and activist Fela Kuti and tried a suya pizza. He also walked around Ikeja City Mall, which he tells me is basically like London’s Westfield. But the best thing about his trip was being able to meet family members.

“I felt happy and excited meeting family members, to put a face to voices I’d heard all my life,” Dammy says. “This might sound weird, but it was also nice seeing family members that added me on social media years before I came.”

Visiting Somalia for the first time was a similarly special experience for Neima, aged 22. “My mum and auntie planned for us to go as a family,” she says. “My cousins and I had never been back home before, so we all got to experience it together.”

The airport experience, however, was quite overwhelming for Neima: “When we got to the airport, I did feel a little bit anxious. There are a lot of people waiting outside for their family members and a lot of people just shouting at you. I had never met these family members that were picking us up from the airport – I just thought they were strangers when they approached us, so we were quite cold towards them. We later found out it was actually our uncle picking us up! When I was there, I tried to do what locals do, but they could definitely still tell I was visiting from abroad. They even had nicknames for the diaspora kids.”

Professor Russell King specialises in migration research at the University of Sussex. He tells me that perceptions of a “home” country for the children of migrants are shaped by a number of factors.

“On the one hand, the homeland is idealised,” he says. “It’s the family home, the home of the diaspora, where people are kind and friendly and welcoming. But the other image is that the homeland is a place where parents struggled – often why the first-generation migrants left in the first place.”

King continues: “In some cases, the return visit is precisely a search for identity. They may have been discriminated against, or have had experiences of racism, and so they feel out of place in British society.”

Despite the challenges that come with exploring a family heritage, there are endless reasons to visit a “home” country – once coronavirus travel restrictions deem it safe to do so. “The more you visit, the more you can reconnect in a meaningful way,” King says. “Visiting just as a one off is much more of a clash of ideas. The local population might also see visitors as more or less tourists, and therefore to be treated as such and exploited.”

When I do visit Dominica and Nigeria, I may be going as a tourist – which isn’t ideal, as I want my experience of these countries to be as authentic as possible. But I know that I’ll be embracing my version of home, however and whenever I’m able to go. And with a heritage and culture as rich as mine, I take comfort in that thought.