In Pictures: How the Coup Played Out in Myanmar

February 5, 2021Myanmar was plunged back into military rule this week, erasing the gains of a young democracy.

The military moved swiftly, detaining civilian leader Aung San Suu Kyi along with the president and other senior government leaders from the National League for Democracy party (NLD). Suu Kyi and ousted president Win Myint were placed under house arrest and hit with obscure charges.

Authority was handed over to army general Min Aung Hlaing, now the country’s leader. But many are still reeling from anger and shock.

Here’s a look at how things played out throughout the course of five dramatic days.

It started early Monday morning.

Phones and the internet were cut off as army convoys rolled through the capital Naypyitaw. Soldiers began rounding up and arresting politicians and representatives, including de facto civilian leader Aung San Suu Kyi. A total of 147 officials, lawmakers and activists would be rounded up over the week, according to the Assistance Association for Political Prisoners.

The raids were timed to prevent parliament from convening after Suu Kyi’s party won a landslide election victory in November, in results disputed by the military but backed by the international community and election observers.

After a yearlong state of emergency was declared, it became clear that a horribly familiar dark chapter in Myanmar’s history was unfolding: the military, which had ruled the country from 1962 to 2010 before a turn towards democratic reforms, was back in charge.

The first moments, now captured in a viral video by exercise instructor Khing Hnin Wai, caught many off guard.

The coup blindsided the world, but also capped months of political tensions that were growing between Suu Kyi and the military after the election.

Protests broke out later on Monday across major Asian capitals following news of the coup and the arrest of Suu Kyi. Though Suu Kyi’s international reputation has fallen over her defense of a violent campaign against Rohingya Muslims in 2017, she remains hugely popular at home and with Myanmar’s diaspora community.

Crowds of Myanmar activists and sympathizers gathered outside the United Nations University in Tokyo to protest the military takeover while violent clashes broke out in Bangkok between riot police and protesters outside the Myanmar embassy.

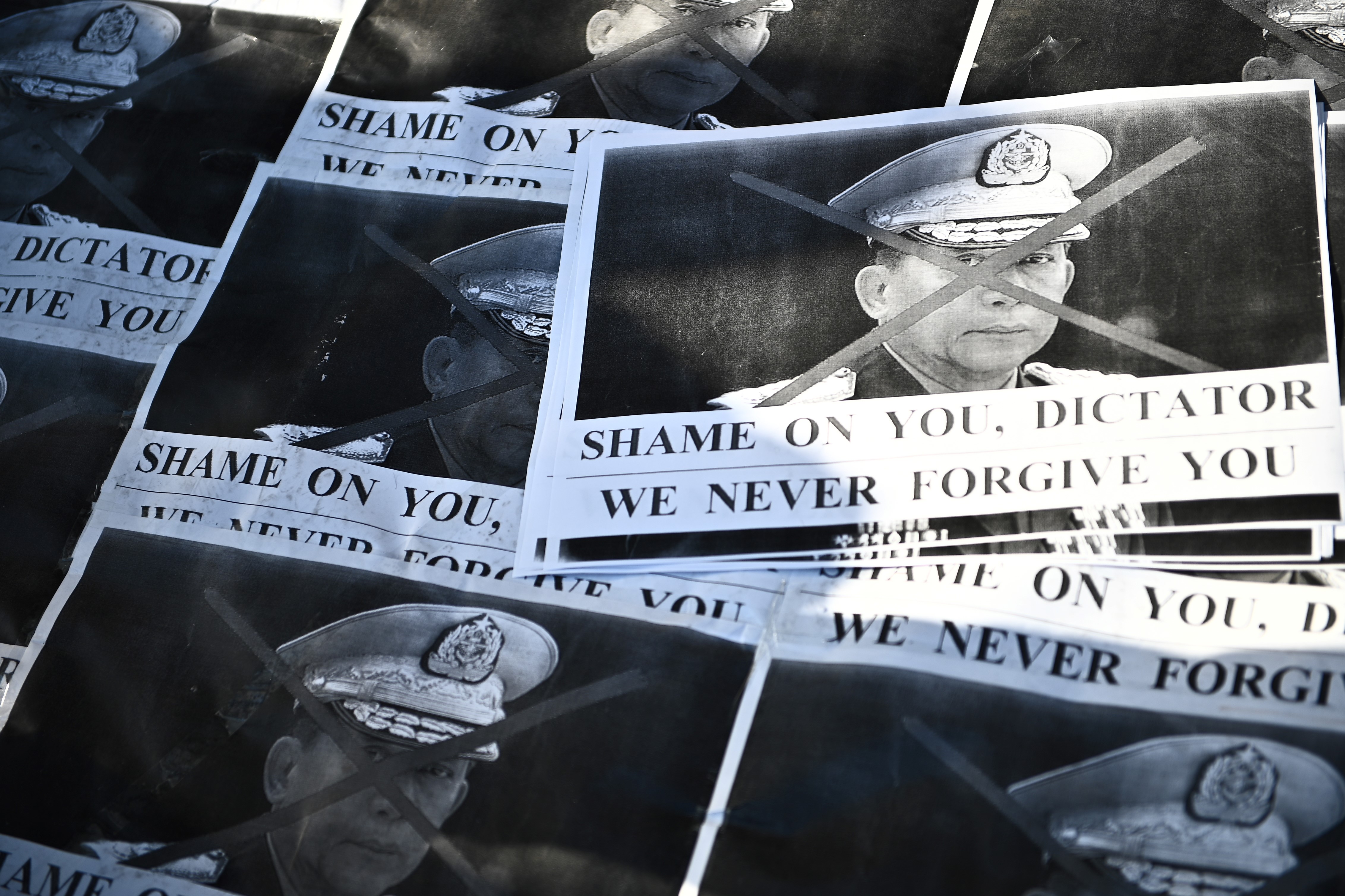

Protesters shouted slogans and stomped on printed photos of Min Aung Hlaing while calling for the international community to act.

“Please tell people that our government is very bad and always bullies the public,” one protester shouted. Others held up posters of Myanmar’s new military leader Min Aung Hlaing with the text, “Shame on you, dictator.”

Back in Myanmar, it didn’t take long for fear to settle in.

Malls, shops and restaurants were shuttered. Panic buying started. Scenes in Yangon and other cities showed people rushing out to supermarkets to buy food and other necessities.

Snaking queues were also seen outside banks and public ATMS as people rushed to withdraw bundles of cash, anticipating that they would be in this state for a long time.

As the reality set in, dissent rapidly spread on Tuesday and Wednesday. Under the name Civil Disobedience Movement, a group launched on Facebook to hit back at the new ruling military government for dismantling democracy in the name of power.

Joining them were doctors and medical frontline workers in the country, overworked and subjected to poor and unsanitary conditions throughout the course of the worsening pandemic.

They called for support as they announced a nationwide strike to oppose the return of junta rule in the country.

“We cannot accept dictators and refuse to obey any orders from the illegitimate military regime,” read a statement issued by medical professionals, which was widely circulated across social media.

“We may not be making noise by taking to the streets but we are supporting this movement from our medical wards.”

Staff at hospitals across Myanmar pinned red ribbons to their blue surgical gowns and proudly flashed the three-finger salute, made famous by the Hunger Games franchise and popularized by protesters in neighboring Thailand and Hong Kong as a symbol against authoritarian rule.

On Wednesday, Suu Kyi’s NLD party confirmed that the 75-year-old leader had been charged with a bizarre violation: possessing illegal walkie-talkies supposedly found during a police search in her home. Win Myint, the ousted president, was also charged, but with breaching coronavirus rules.

But over Wednesday and Thursday anger was spreading. All over Yangon residents banged pots, pans and honked horns in a deafening clamor meant to “drive out the devils.”

“People are fearing anger, fear and loss,” one person told the Guardian, declining to share their names out of fear of reprisals.

Anger was also fueled by a military order on Thursday to shut down Facebook for three days. In the morning, millions of Facebook users in Myanmar were greeted with blank, white screens and error messages.

Facebook is the country’s most popular social media site and restricting its access cuts off millions in Myanmar from the rest of the world. It serves as a reliable messaging service and is a main source of information. It is also used by many businesses.

“We urge the authorities to restore connectivity so that people in Myanmar can communicate with their families and friends to access important information,” the social media company said in a statement.

Local internet service providers and telecommunications firms later confirmed that they complied with requests from the authorities to block access to the site.

Myanmar’s military blocked the site to promote “stability”. But it overlooked a key fact: that it is now dealing with a new, tech-savvy generation.

Thousands of Facebook users navigated the blockage with VPNs. Others flocked to Twitter instead to mobilize their cause against the military.

Late Thursday, the UN Security Council released a statement demanding the military release all civilian leaders. On Friday morning, however, security forces arrested yet another of Suu Kyi’s close allies.

As calls grow to cut ties with businesses owned by the military, Japan beer maker Kirin said it would drop its joint venture with a military-owned company that brews the Myanmar Beer brand. The U.S. has also threatened a new round of targeted sanctions.

And resistance continues to grow on the home front. Both teachers and students demonstrated in the former capital Yangon on Friday.

The first five days of the coup appear to be only the beginning, as the military faces widespread resistance from a furious citizenry. This new normal is poised to last for months.