China Has Ties With Both Sides of Myanmar Coup. This Could Get Awkward.

February 4, 2021Referring to the Myanmar coup in state media as a “major cabinet reshuffle” and asking Western powers not to add “fuel to tensions,” China’s initial reluctance to utter the four-letter word stood out amid the chorus of global condemnation.

But Beijing’s cautious tone, along with its refusal to condemn the coup or take sides, signals the awkward position it is now in after years of cultivating warmer ties with ousted Myanmar leader Aung San Suu Kyi. The 75-year-old remains under house arrest and is facing charges after being detained on Monday in sweeping pre-dawn raids that toppled the civilian leadership.

Since coming to power in 2015 elections and ending decades of military-backed rule, Suu Kyi has presided over improved ties with China as U.S. influence waned. Beijing stood by her and the military during a torrent of Western-led condemnation over the 2017 Rohingya crisis.

In the first visit by a Chinese president since 2001, Xi Jinping visited Myanmar in early 2020 to try to move ahead billions in Chinese-backed projects, including a deep sea port, a controversial dam and an economic corridor.

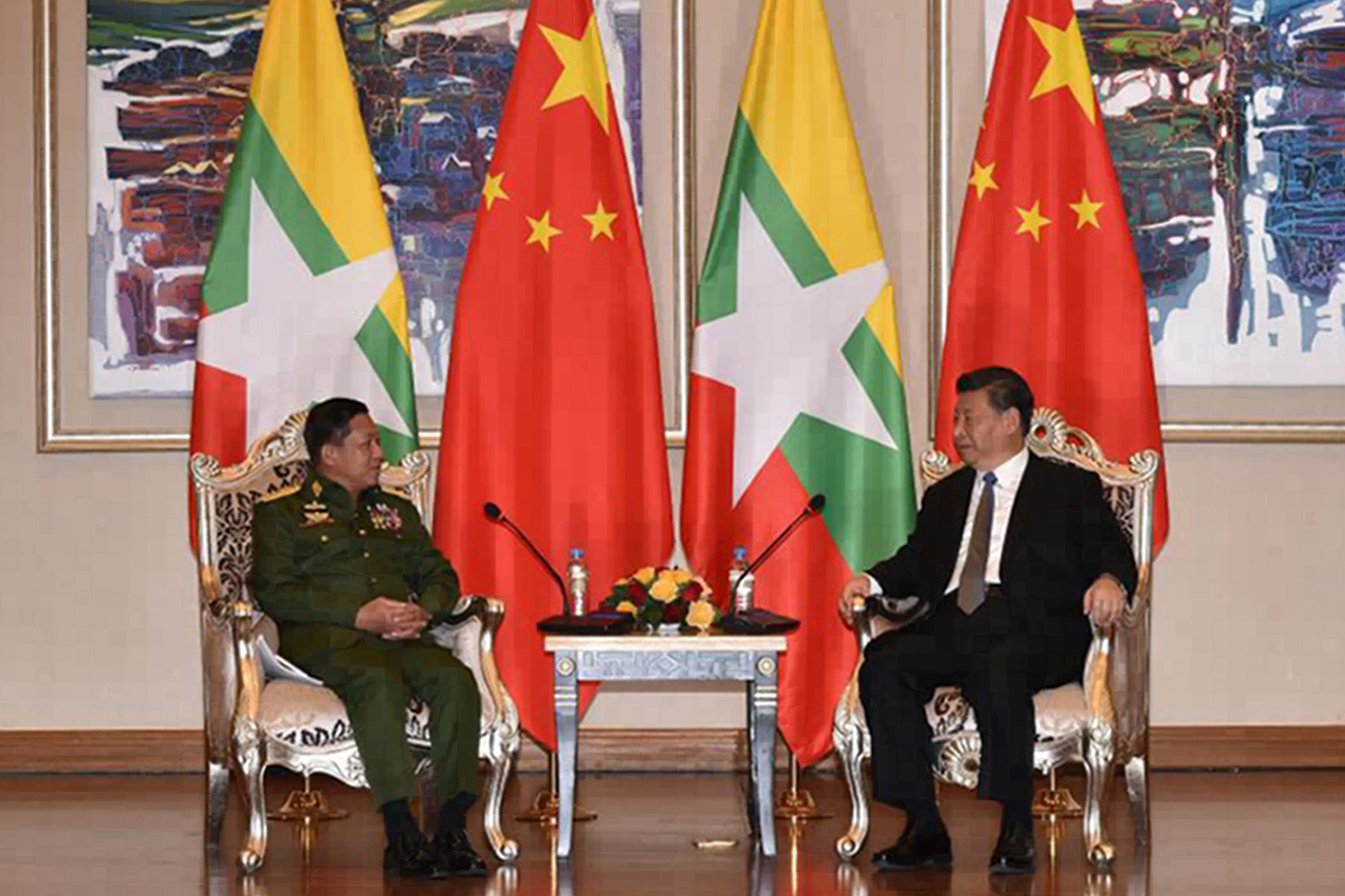

Foreign ministry chief Wang Yi also visited Myanmar last month and met with army chief Min Aung Hlaing, who would later become the mastermind of the coup. While this led to rife speculation that China knew about the plan in advance, experts believe they were just as blindsided as the rest of the world and will now need to “recalibrate” its approach.

“Chinese financial and military capital is important for marginalized and weaker countries like Myanmar, but this doesn’t imply political finesse and acceptability across the spectrum,” said Avinash Paliwal, an international relations professor at the School of Oriental and African Studies in London.

Paliwal said Beijing’s quiet stance on the military coup shows the limits of China’s power in Myanmar, where there is still a lot of potent anti-Chinese sentiment among people and in many sections of the military.

To observers, China’s muted reaction hardly comes as a surprise and remains consistent with its long-standing claims of non-interference, a principle that the ruling Communist Party government has often cited in rebuking Western criticism of human rights violations.

“[In Myanmar] China has been playing both hands in the last five years,” Kalvin Fung, a Southeast Asia politics researcher at Tokyo’s Waseda University, told VICE World News.

“On the one hand, Beijing has maintained a relationship with Myanmar’s military. On the other, it has also been busy cozying up to Aung San Suu Kyi, building better relations with her then-government, especially after the Rohinya genocide accusations that isolated it from the West.”

But the junta will still need Beijing to shield it from action at the UN Security Council—which it did this week when refusing to agree to a statement condemning the coup—and if the U.S. applies a tougher raft of sanctions.

“Many Southeast Asian countries like Myanmar and Cambodia, which are under authoritarian rule, care more about China than relations with the west,” said Roger Huang, a researcher on Southeast Asian politics and lecturer at Sydney’s Macquarie University.

“U.S. sanctions and threats from the UN are no longer relevant to these countries in the current political landscape as the pandemic continues because diplomatic relations with the Chinese Communist Party are far more important and beneficial.”

“U.S. sanctions and threats from the UN are no longer relevant to these countries in the current political landscape as the pandemic continues.”

For now China is refusing to be drawn to pick a side, offering little more than vague assessments and answers.

In response to a question about the coup, a Chinese foreign ministry spokesman said that as a “friendly neighbor,” it hopes all sides can work out their differences and maintain stability in the region.