Rohingya Brides Thought They Were Fleeing Violence. Then They Met Their Grooms.

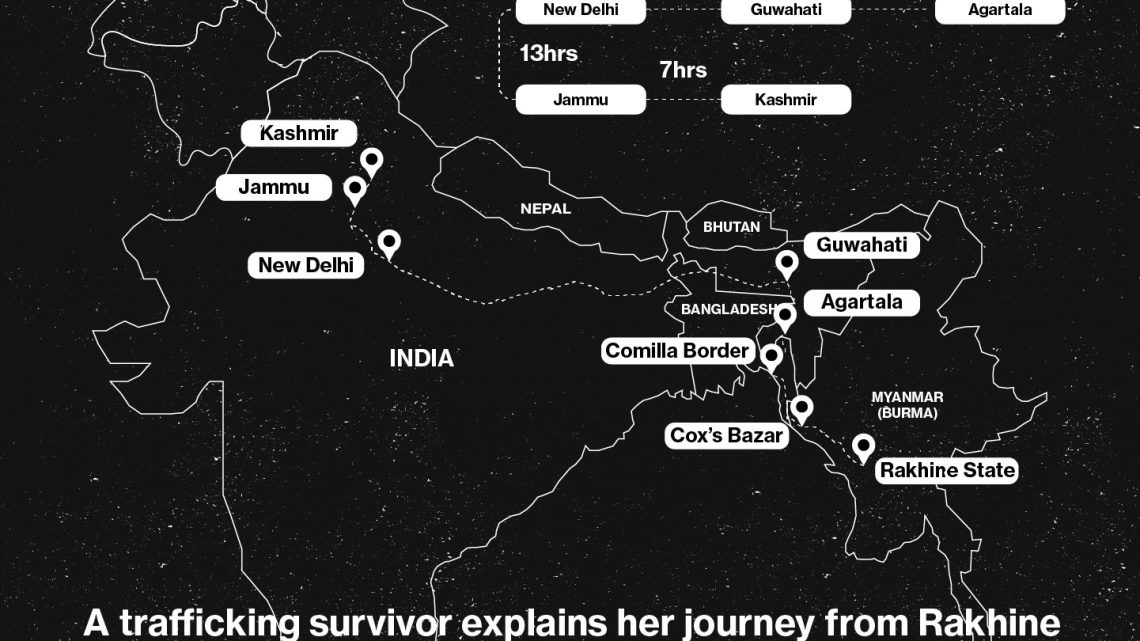

January 25, 2021KASHMIR, India—Her baby cradled in her arms, Muskan recalls the winter night when she was duped into traveling more than 2,000 miles to be married to a man 30 years older than her.

“My legs were swollen and hurting because of the beatings and intense cold,” Muskan told VICE World News at her house in Kashmir, a stunning but conflict-ridden mountainous valley administered by India. “I felt miserable. I couldn’t see a way out.”

Five years have passed since she made the harrowing journey from her home in Myanmar. But Muskan can’t forget the horror of being held captive in the middle of the freezing winter, locked in a room without a toilet. The traffickers wouldn’t even let her and the other young trafficked women leave to use the bathroom. Muskan said their male captors beat them when they refused to marry complete strangers, often older men suffering from mental disabilities. Many of the marriages were arranged by families who struggled to find a caretaker for these men, she said.

Muskan, who is now in her 30s, was eventually sold for 100,000 Indian rupees ($1,370) to a 60-year-old farmer in Kashmir who was mentally ill.

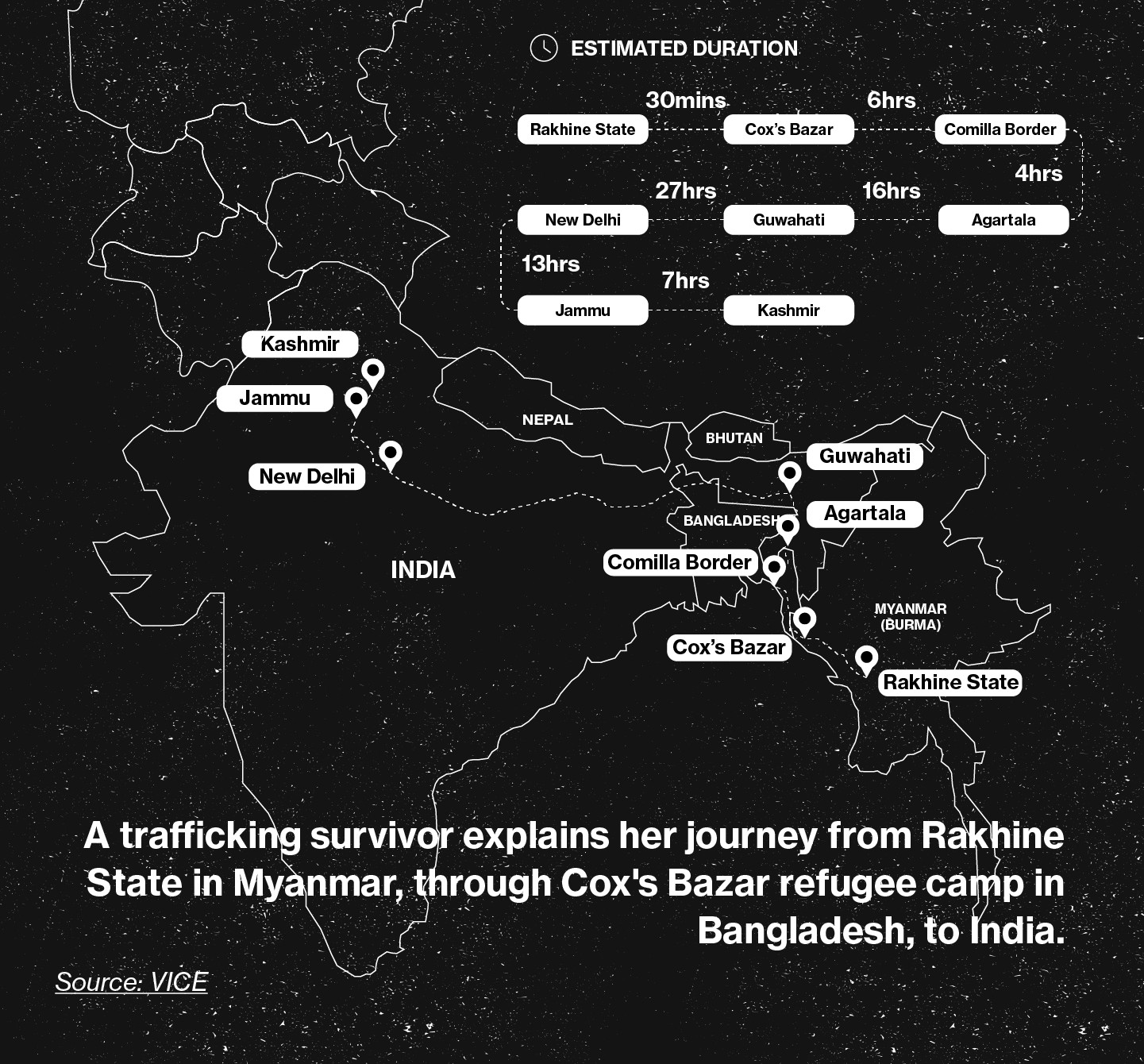

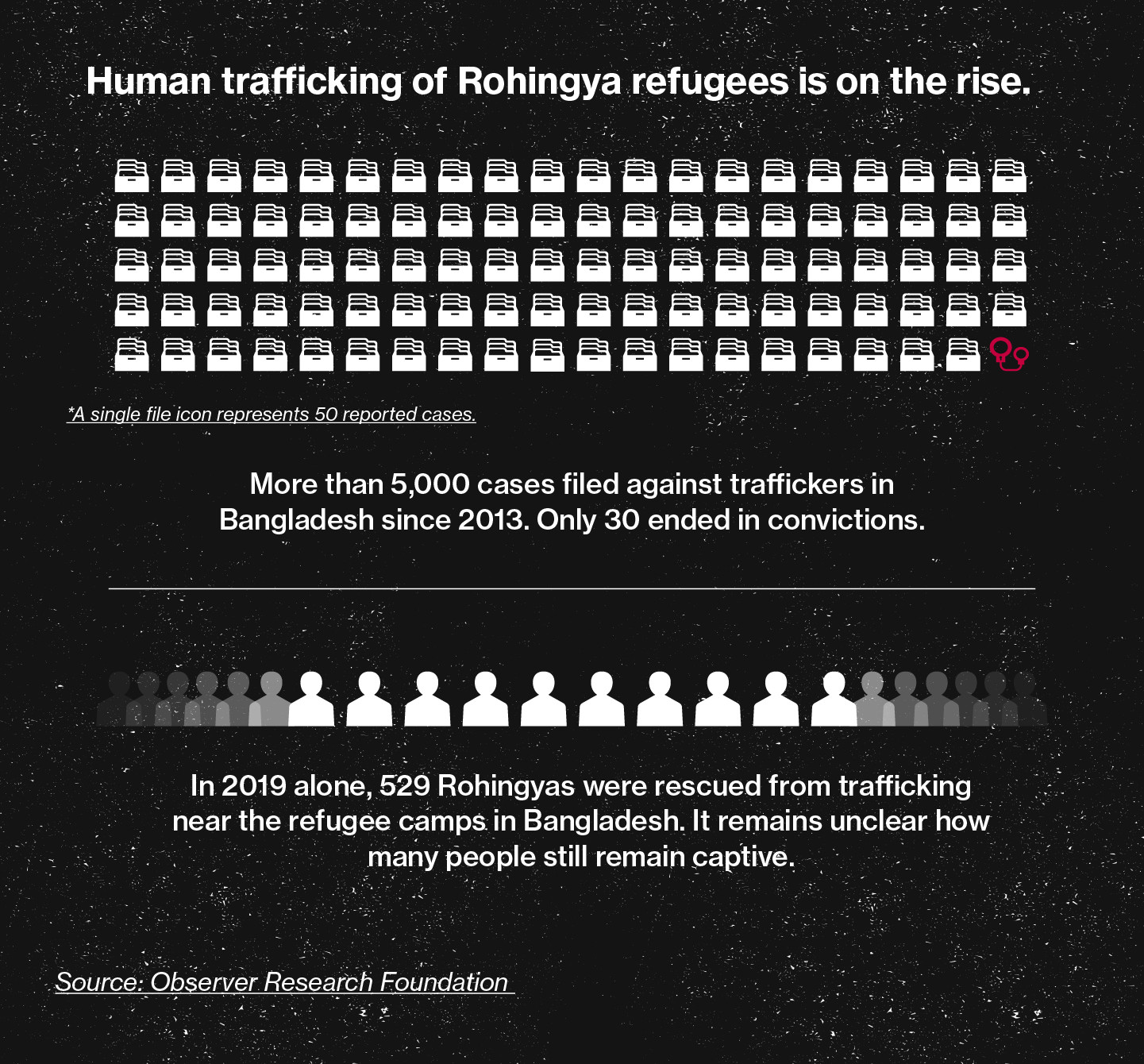

During a nine-month investigation, VICE World News tracked the jarring journeys of four Rohingya women who were trafficked from Myanmar’s northern Rakhine state to Kashmir over the past decade. To protect their identities, pseudonyms are used.

In separate interviews, the women said they were tricked by human traffickers who promised them marriages to “young and handsome bachelors.”

The four women, speaking on the condition of anonymity for fear of backlash from the community they now live in, said they were sent from Myanmar via Bangladesh, then handed over to Indian traffickers in Kashmir, who held them for days in appalling conditions. They were denied food and medical care as they begged to return to their families in Myanmar.

The Myanmar military’s brutal crackdowns on Rohingya Muslims have affected their lives in many ways, including fueling a market for the trafficking of brides outside the country. In 2017, the Myanmar military’s latest systematic attack against the community forced over 740,000 Rohingya Muslims to flee the Buddhist-majority country by crossing the Naf river into the southeastern part of Bangladesh.

The sudden mass arrival increased offers for Rohingya brides in trafficking networks, according to experts.

“There was a sudden surge in demand for Rohingya women after the 2017 mass exodus in Myanmar, while trafficking among Bangladeshi women went down, though it’s still prevalent,” said Salma Ali, president of the Bangladesh National Women Lawyers’ Association (BNWLA) and an anti-trafficking activist.

Hasina Kharbhih, founder of Impulse NGO Network, a human rights NGO in the northeastern Indian city of Shillong, added that many Rohingya women end up in Kashmir and Hyderabad because of significant Muslim populations there.

According to Imtiyaz Ali, a Kashmir-based social worker with Childline India, Kashmiri families pay the equivalent of about $680 to $1,370 for Rohingya brides, an amount much less than the minimum expenses for a Kashmiri wedding, around $6,831.

“More people find it economical to buy a bride than organize a wedding,” Ali said.

Tricked and betrayed

But the longstanding persecution of the Rohingya people in Myanmar has created incentives to get out of Rakhine state even before the 2017 crisis. The Buddhist-majority country has systematically harassed the stateless Rohingya for decades, leaving many to take risky journeys by boat to foreign countries in an attempt at a better life.

Muskan, who hails from Rakhine’s Inn Din village, which would become the site of an infamous massacre two years after she left, said traffickers would often come looking for families desperate to marry off their daughters outside Myanmar.

In September 2015, a Rohingya trafficker from Myanmar showed her photographs of men who seemed wealthy and handsome, and told her they were Kashmiris. That was the first time Muskan said she heard the word “Kashmir.” Within a week, the trafficker met her parents, who were farmers, and assured them she would marry the man she had picked from the photos. Her family paid him $150 for her safety.

Zubaida, who lived in Maungdaw town in Rakhine state, was also tricked. She was 16 years old when her parents paid $15 to a trafficker to get her out of Myanmar. That was the only way she said they could help her escape growing persecution of the community in 2012 when anti-Rohingya riots killed hundreds. But once in Kashmir, the trafficker sold her for less than $683 to a 37-year-old man who also suffered from psychological problems.

Zubaida, who now lives in Kashmir’s Anantnag district and is a mother to a six-year-old child, is worried about her future with her husband. “He is old. What will happen when he dies? I would have run away if I did not have any children,” she said.

Farida, 30, has been living in Jammu & Kashmir’s Pulwama district for more than five years. She said her first husband was killed in Myanmar’s Rakhine state along with other Rohingya men in an attack by Myanmar soldiers in 2011 that could not be independently verified. To escape the same fate as her husband, Farida fled Myanmar, swimming across the Naf river to Bangladesh with her toddler tied behind her back.

In 2015, having lived in a Cox’s Bazar camp for four years, she paid a trafficker more than $1,100 to escape to India. Farida said that she had no way of knowing that the trafficker would sell her to a man double her age for $685. She said she is also aware of at least two Rohingya women from Cox’s Bazar who were brought to her village in Kashmir in May 2019.

Unlike the other brides, who at least knew they were being brought to India, Begum, a 32-year-old Rohingya woman from Rakhine state’s Maungdaw district, was told that she was being taken to Bangladesh for marriage in 2011.

“It takes only a day to reach Bangladesh from Rakhine but we kept traveling for 15 days and nights changing several vehicles on the way,” she said.

By the time she realized she was being taken to another place, her group was caught by the police. She was told she was in India’s south Kashmir. She said the police sent her to a nearby Rohingya refugee camp, where she was taken in by a sympathetic family. But this place was also infested with traffickers and a single woman like her soon attracted attention. She wanted to go to Bangladesh, but a trafficker she met at the camp told her that there was no way to go back to Bangladesh. The only option was to get married to a man from Kashmir. A trafficker later sold her for more than $820 to a 32-year-old Kashmiri man who couldn’t manage to get a bride locally.

Life in Kashmir

It is common for trafficked brides to be exploited in their marriages, according to interviews. They are frequently subjected to discrimination on the basis of their color, facial features, language and nationality. Many brides complain of being treated as laborers; they are made to work non-stop in the farms. The brides are not allowed to interact with anybody except their husbands and in-laws.

Zubaida complained that the work at her in-laws' apple orchards caused her perennial back-ache. She has been using a posture-corrector brace since 2018. “I am treated like a servant here. My medicine costs over INR 1,000 ($13.7) but all I am given by my in-laws is INR 200 ($2.74),” she said.

Pointing towards her tattered salwar kameez, a traditional outfit worn by women in South Asia, she said her in-laws treat her differently from other daughters-in-law and physically abuse her because she’s Rohingya.

During an interview with VICE World News, Zubaida was still wearing the same oversized male chappals, or slippers, from her younger days years ago in Myanmar before being trafficked to India.

Muskan’s life in Kashmir, where she is married to a farmer and has two children, is similarly miserable and abusive.

“My husband once battered my head with a wooden log that resulted in many stitches. He threatens to throw me out of the house and keep the two children. There is suffering in my homeland too, and this place is no different.”

Muskan said this is her husband’s third marriage—his previous wives left him because of his abusive behavior. He often beats her in front of their children and his relatives. She pulled up her outfit to show a long, deep scar on her lower abdomen. She said her husband beat her for consulting a doctor for an infection she caught after a caesarean section for her second child. The beatings were so severe that she had to get stitches again.

“Sometimes, I just want to die to get rid of this suffering,” said Muskan, breaking into tears.

She has tried to seek help at many police stations to lodge a complaint against her husband and his relatives, but none of them have been addressed. Her only solace from the abuses lies in meeting a few other Rohingya brides who live in the same district.

She is among the fortunate few who, after much resistance from her husband, was able to speak to her family in Myanmar on a few occasions. But she is also expresses weary resignation about her fate.

“I miss my family, but this is my home now.”

No end in sight

Over one million Rohingya Muslims have now fled Rakhine state, where they had lived for centuries. The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) told VICE World News an estimated 866,457 Rohingya live in the largest camps called Kutupalong and Balukhali camps in Bangladesh. In India, there are only about 18,000 Rohingya refugees as of Nov. 31, 2020.

A United Nations report published in 2019 noted that Rohingya women and girls suffered the most at the hands of the Myanmar army; they were gang-raped, tortured and held captive as “sexual slaves” at military bases.

The humanitarian crisis has made Rohingya women in Myanmar and Bangladesh a target for human traffickers who lure them with dreams of marrying rich and handsome men in India.

Human rights activists combating trafficking say that Rohingya women are being trafficked through India’s northeastern states as well as West Bengal in the east.

“India shares a 4,097 kilometres-long [2,545 miles] porous border with Bangladesh, but there are not enough people managing it. If you go to Malda city in West Bengal, you’ll realize that it is an open field with no fencing at all,” said Tapoti Bhowmick, secretary of Kolkata-based human rights NGO Sanlaap.

Impulse NGO Network’s Kharbhih said there is no clear data for Rohingya women trafficked into India due to lack of documentation by government and rights monitors. But it is happening regularly. “Trafficking of Rohingya women through the borders of India’s northeastern states including Mizoram, Manipur, Assam, Tripura and Nagaland has been going on non-stop.”

Code words: Mishti & Sandesh

Despite huge risks like being detained, imprisoned, and even re-trafficked during the course of an illegal crossing, many Rohingya women in India often risk their lives to reconnect with their families in Myanmar and Bangladesh.

VICE World News met at least 10 Rohingya women at Cox’s Bazar camp who managed to return to Bangladesh after being trafficked to India. These women, who escaped their abusive husbands in Kashmir, said they worked as laborers and did odd jobs to save up money so they could pay traffickers to take them back to Bangladesh. Some received financial support from their families to return.

All of them said that there is a close nexus between traffickers, travel agents, transporters, recruiting agencies, and even government officials operating in both the countries.

The Rohingya women VICE World News interviewed in the refugee camps in Bangladesh claimed that the border guards in Bangladesh and India colluded with traffickers to facilitate their entry into both the countries.

They recounted that traffickers and border guards would use code words like sandesh and misti (sweets in the Bengali language) when the women were made to cross the border using auto rickshaws for transportation.

“The border guards would then show up, take the money, and give the vehicle a free pass,” said 20-year-old Halima at the camp, who was part of a group of women trafficked in 2018. “This happens either at the crack of dawn, after the morning prayers, or late at night.”

Abida, a 31-year-old in the same trafficked group as Halima, said she saw two Bangladesh Border Guards ask her trafficker for cash to let them through the border.

Anti-trafficking activists say neither the Indian government nor Myanmar has addressed the cross-border trafficking of Rohingya women. In a conference in December 2020, the Border Security Force and the Border Guard Bangladesh decided to conduct joint night patrol at “vulnerable patches to thwart cross-border crimes including smuggling of narcotic substances, cattle, and human trafficking.”

In January 2020, the Bangladeshi government agreed to teach Rohingya boys and girls up to the age of 14 under the Myanmar school curriculum, and give them skills training, in the hope of combatting human trafficking in the camps.

The International Organization for Migration (IOM) has also initiated many steps like creating awareness programs for women and children on human trafficking and “cash for work” initiatives in the camps in Cox’s Bazar. But there are systemic problems like the burgeoning population of Rohingya in the congested camps, lack of human resources, and poor anti-trafficking laws, all of which slow down the process.

“We are reaching out to Rohingyas and explaining if any person comes in the camps and offers a passport or plane ticket for free, you have to understand that it’s not real,” said George McLeod, an IOM spokesperson in Bangladesh.

Women of no land

VICE World News tracked down Zubaida’s brother, Alam (also a pseudonym), in Nayapara, one of the two government-run refugee camps in Bangladesh. Alam seemed hesitant about the possibility of getting Zubaida to return to the family.

“How will I give her a better life when I have no financial support myself?” he said. “There’s no work for most Rohingyas staying at the camp. We are not even allowed to move outside the camp in Bangladesh. We were chased away from Myanmar and this country is also not our land.”

Besides, the threat of traffickers looms large at the camps in Bangladesh. Families of scarce means with daughters, widows, and even single mothers often catch the attention of traffickers. Alam fears that even if Zubaida returns, she’d soon be lured into another trafficking racket.

In Kashmir Zubaida still hopes that she can meet her parents one day without having to go through traffickers. But if she has to stay in India, she wants to be treated with equal respect as other Kashmiri daughter-in laws.

“We want acceptance in the Kashmiri society—as wives and not as laborers,” Zubaida said.

Muskan has a similar request: “Please help me get my status and fundamental rights as a wife. My kids have rights too. I was deceived and sold but now just allow me to live with dignity here. I don’t want to be deported, put into jail, or a detention camp. I have seen enough pain now…could you write this to the government?”

As far as Farida is concerned, she has already made a few attempts to escape from her abusive husband and run away to Bangladesh. “Please, don’t tell my husband. Help me run away to Bangladesh,” she pleaded, afraid of being caught speaking by her husband.

For Begum, who is desperate to reunite with her family in Myanmar, it’s different.

“You won’t find belonging anywhere except your own home,” she said, pulling her 4-year-old daughter close to her chest.

Follow Pari Saikia on Twitter.

This story was made possible by Impulse Model Press Lab Four-Week Cross Border Human Trafficking Journalism Fellowship by Impulse NGO Network.