Royal Defamation Cases Soar in Thailand As Authorities Seek To End Protests

January 5, 2021Dressed in crop tops with jabs at the monarchy scrawled across their bare midriffs, some of Thailand’s most prominent activists parade around a busy Bangkok mall, in a provocative and public challenge to one of the world’s toughest royal defamation laws.

The Dec. 20 demonstration happened in the wake of dozens of activists being accused of insulting the kingdom’s ultra-powerful monarchy within a few weeks — the highest number in years. The youngest accused is a 16-year-old teenager who participated in a street fashion “runway” rally in October.

“If we don’t stand up to fight for (the teenager) today, in the future, maybe an elementary student will be charged. Who knows?” protest leader Parit “Penguin” Chiwarak declared in the middle of the massive Siam Paragon mall, as bewildered shoppers looked on and snapped photos.

Thailand’s lese-majeste law carries up to 15 years in prison, limiting open discussion of the monarchy until pro-democracy protests shattered the taboo in demonstrations that swept the country last year. Though it was not initially used in the monthslong saga of mass gatherings, water cannons and tear gas, the law is back in force in what observers say is an effort to stamp out the popular youth-led movement once and for all.

A total of 39 people have been charged in recent weeks, according to monitoring group Thai Lawyers for Human Rights, including two cases in the first three days of this year. That compares to zero new cases in 2019.

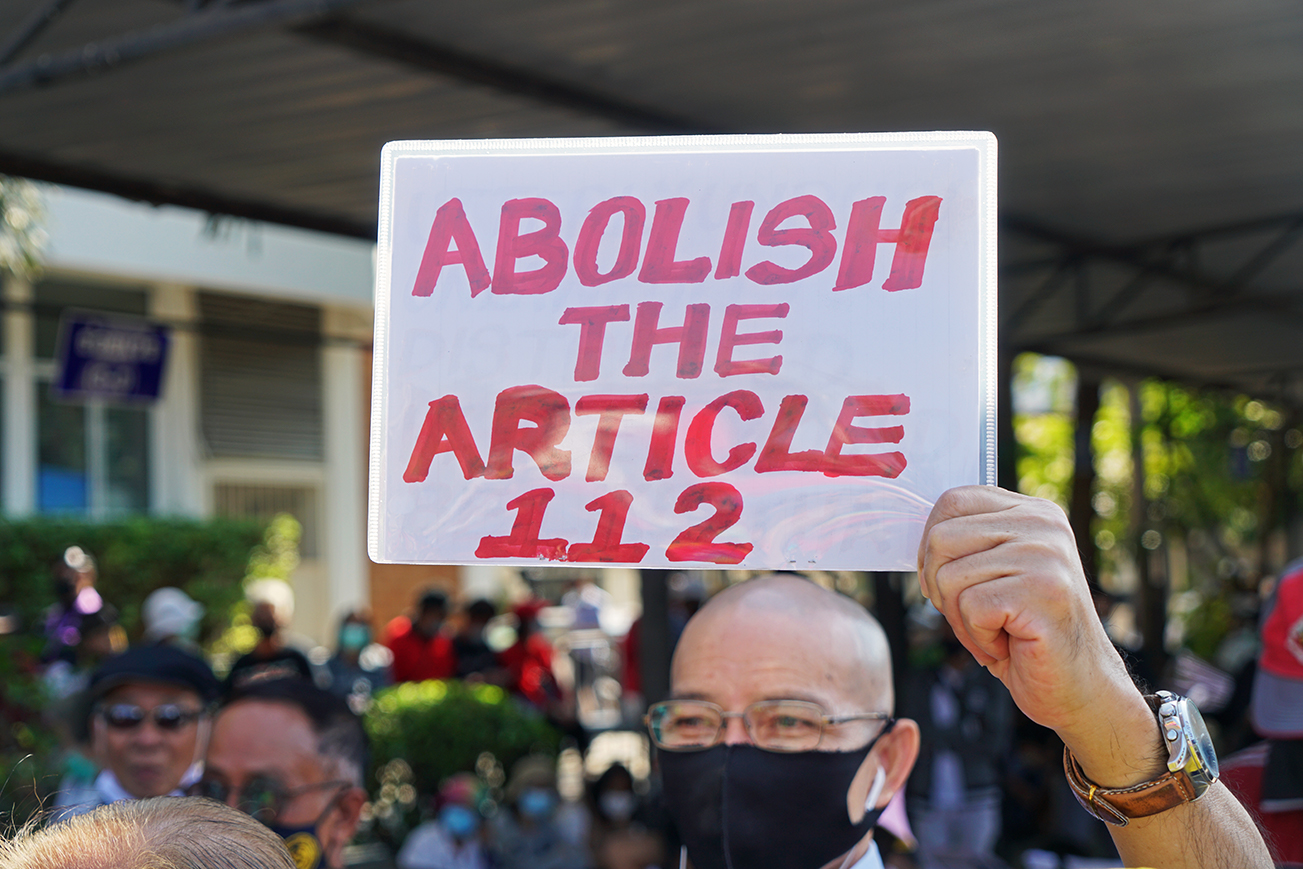

Some protestors face multiple counts of the law, known as Article 112 in the criminal code. Parit, who has been at the forefront of the demonstrations, is staring down as many as a dozen.

Article 112 makes it a crime to insult, defame, or threaten the king, queen, heir apparent or regent. Usage declined under Thai King Maha Vajiralongkorn, who ascended to the throne in 2016 after the death of his long-reigning father.

But rights groups believe the resurgence after a nearly three-year hiatus is tied to the growing and historic public debates over the monarchy in Thailand, which went from unheard of in early 2020 to ubiquitous in signs, plaques and graffiti as protests dragged on.

Among 10 demands put forward by demonstrators are calls for the king’s powers to be curbed, for the royal family’s immense wealth to be managed more transparently, and for Article 112 to be abolished. In one of many protests focusing on the palace, demonstrators rallied outside Siam Commercial Bank in November. The king is reportedly the largest shareholder in the bank.

Sunai Phasuk, senior Thailand researcher at Human Rights Watch, told VICE World News that the uptick in cases is a “clear message” that these calls will not be tolerated, and there will be no compromise with protesters who seek royal reforms.

“The scope of the charges has been broadened further and further beyond the text of the law. Now, literally the slightest critical reference to the monarchy is punishable.”

The hard-and-fast return of the law, he added, sets new ground rules for the movement and is the government’s “last resort” to quash the demonstrations.

The Escalation

When protests began at the beginning of the year and picked back up in June after a brief pause due to the coronavirus outbreak, the government initially responded with lesser legal charges such as the Public Assembly Act or the Emergency Act, according to Matthew Bugher, head of the Asia Program for freedom of expression group Article 19.

The penalty for violating the Emergency Act is two years in prison and/or a fine of about $1,300. Violators of the Public Assembly Act face a fine of little more than $300.

While the government maintained that the State of Emergency, announced in March, was adopted to combat the spread of COVID-19, by the end of August 63 people were accused of violating the decree for their involvement in the protests.

But demonstrations still grew quickly. While protestors started by demanding major structural changes to the government and constitution, the conversation ultimately shifted to include reforms of the monarchy in August.

Legal reactions from the state escalated as protests showed no signs of slowing down.

The most violent clashes between demonstrators and authorities occurred on Nov. 17. As protestors cut through razor-wire barricades near the parliament and hurled paint at riot police, police responded with water cannons and tear gas.

Several days later, Prime Minister Prayut Chan-O-Cha said that "all laws and all articles" will now be used to prosecute demonstrators, which many interpreted as the return of Article 112. It was in stark contrast to a speech he gave earlier in the year in which he said the royal defamation law would not be used at the request of the king.

The activist Parit was the first to be officially accused of violating the royal defamation law on Nov. 24.

The sudden sweeping use of the law drew heavy criticism internationally including from the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights. In response, a government spokesperson said that Article 112 is only being used against violators of the law in order to protect the "rights and reputation" of the monarchy, not to restrict people's freedom of speech or expression.

Meanwhile, the palace has not made an official comment since the start of the protests.

Not Backing Down

Critics point out that the law contains very broad language that enables demonstrators to be charged arbitrarily, making it the government’s most powerful political weapon.

“Some of the cases that have been brought recently are really ridiculous,” Article 19’s Bugher said, highlighting an example of an actress being accused after merely writing “very brave” on her Facebook page, repeating words used to praise a pro-royalist supporter.

The 16-year-old teenager facing charges (VICE World News is not using his name for privacy reasons) after appearing at the dress-up rally in October is not a protest leader. Though many high school students have joined the movement and appeared at rallies, he says he has never spoken out at protests. He had no idea that he would be facing prison time for taking part in what was essentially a satirical catwalk alluding to the fashion shows of one of the king’s daughters, who is a prominent designer in the country.

“I didn't think it would bring a lot of attention. I merely wore a crop top and jokingly wrote words on my body,” he told VICE World News, pointing out that there were plenty of rally attendees back in October that dressed similarly. The crop top is a reference to pictures of the king abroad that have appeared in the past in European tabloids. It has become a common costume at protests for months.

He said he was “shocked” to have received the summons but said he was not afraid.

“I’m not scared about what will happen to me because I’m confident that I did nothing wrong,” he said.

Despite facing prison time he says he will continue participating in the movement. He wants to represent the youth fighting to scrap 112, which he says is losing its power the more it is handed out.

“The more you use the law the less sacred it is and the less we are afraid of it,” he said.

Observers agree that sweeping use of royal defamation charges will not be the magic bullet that halts pro-democracy protests. Instead, it seems to be throwing fuel on a fire.

“Thai authorities don’t seem to be able to create a climate of fear that silences critics of the monarchy. On the contrary, the mood among supporters of the pro-democracy movement is becoming more defiant,” said Human Rights Watch’s Sunai.

“So this is a scare tactic but is not going to work.”