An Illustrated Calendar of Everything That Went Wrong in Malaysia This Year

December 30, 2020As most Malaysians will recall, 2020 started off on a quiet and uneventful note, a welcome change from the political upheavals that many had come to associate with their country.

A democratically-elected coalition government was in charge, ending a vicious cycle of corruption and power struggles while various societal issues and environmental concerns were finally being addressed.

(Of course, there was chatter about a mysterious “flu” infecting hundreds in Wuhan, China. But that was a problem which was far away.)

To global observers, the country was on the mend and life seemed to be looking up.

So nobody was prepared for what would come next.

Here we explain, with help from Malaysian political graphic artist Fahmi Reza, the nonstop drama that unfolded over the course of the year.

Heated rumors began swirling online in February about a growing rift in the Pakatan Harapan government between two-time prime minister Mahathir Mohamad and party chairman Anwar Ibrahim, also his long-time political rival. The feud went on to become the subject of an important meeting held at the Sheraton hotel in the city of Petaling Jaya.

Following that, several political parties gathered for closed-door talks, fuelling speculations about party infighting and an impending political crisis.

The shocker came on the afternoon of Monday, Feb. 24 when Mahathir announced his dramatic resignation as prime minister. The 94-year-old’s actions would go on to trigger the collapse of his government and the rising of a new one, the Perikatan Nasional political coalition - made up of conservative and nationalist politicians.

It was also then that its leader Muhyiddin Yassin would be controversially brought into power, becoming the eighth prime minister of Malaysia.

March brought a new and dangerous threat.

In January, eight Chinese tourists brought the little-understood disease with them when they arrived in the southern state of Johor, after coming into contact with an infected person in neighboring Singapore. But it wasn’t until late February that Malaysian health authorities would confirm the country’s first official case of the virus.

It didn’t take long for the situation to spiral out of control as virus clusters began to emerge, the largest being a religious gathering held at a mosque in Kuala Lumpur. Within weeks, Malaysia recorded thousands of active cases and briefly became the worst-affected country in Southeast Asia.

By mid-March, the virus had been reported in every state and federal territory in the country and a nationwide lockdown, dubbed the “Movement Control Order” (MCO), was declared on Mar. 16. It would be the first of many restrictions.

Falsehoods about the disease proved to be as contagious as the virus itself. The government was forced to address a series of bizarre news that spread like wildfire on social media. These included public fears about packages sent from China being a source of virus transmission, a prisoner who supposedly died after eating a virus-tainted mandarin orange, and even outrageous claims of infected individuals behaving like zombies.

Malaysia’s first lockdown sparked a huge range of public emotions in April: anger, fear, irritability and restlessness. Tensions ran high in many households.

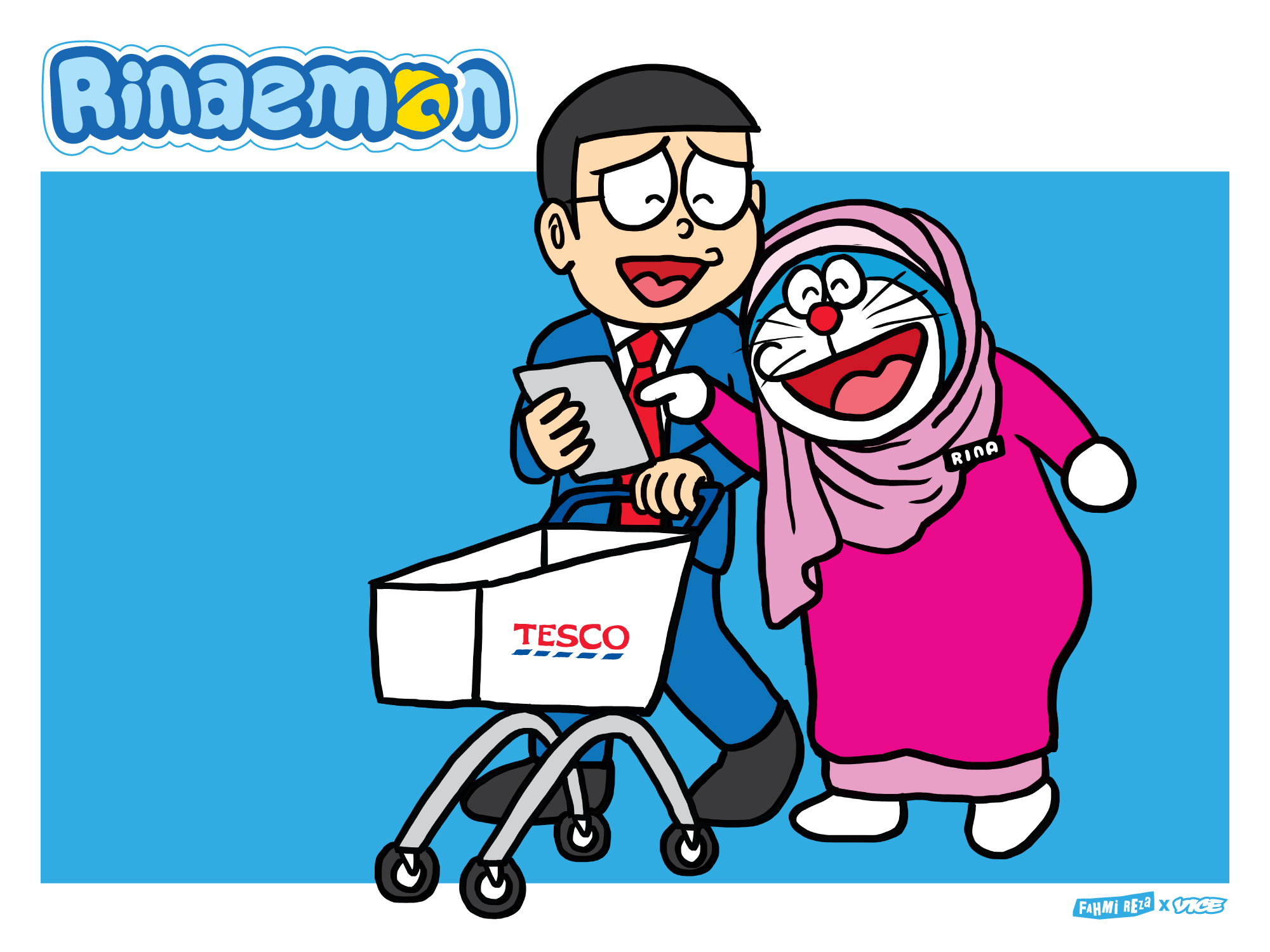

The government’s solution to keeping the peace? Advising Malaysian women to put on make-up while working from home and to be “docile and subservient” to their husbands by talking like the beloved male anime robotic cat Doraemon.

But the unsolicited advice didn’t stop there: popular supermarket chain Tesco released a grocery guide aimed at helping clueless husbands with their shopping.

The hilarious list titled, “Now All Husbands Can Shop”, featured pictures of chicken cuts and various types of fish, meat and vegetables. “To all the ketua rumah (head of households), we understand that things may get confusing at times like this. Use this handy guide for your grocery shopping trips,” Tesco Malaysia said.

Unsurprisingly, the stunt went viral and attracted an enormous amount of public ridicule.

While a number of Malaysians pointed out that women often didn’t need to rely on men to do the grocery shopping, some husbands joined in the conversation. “Looking at this list just hurts my head. I rather stay home and look after my kids while my wife does the shopping, saves everyone the trouble and anxiety,” one guy joked on Facebook.

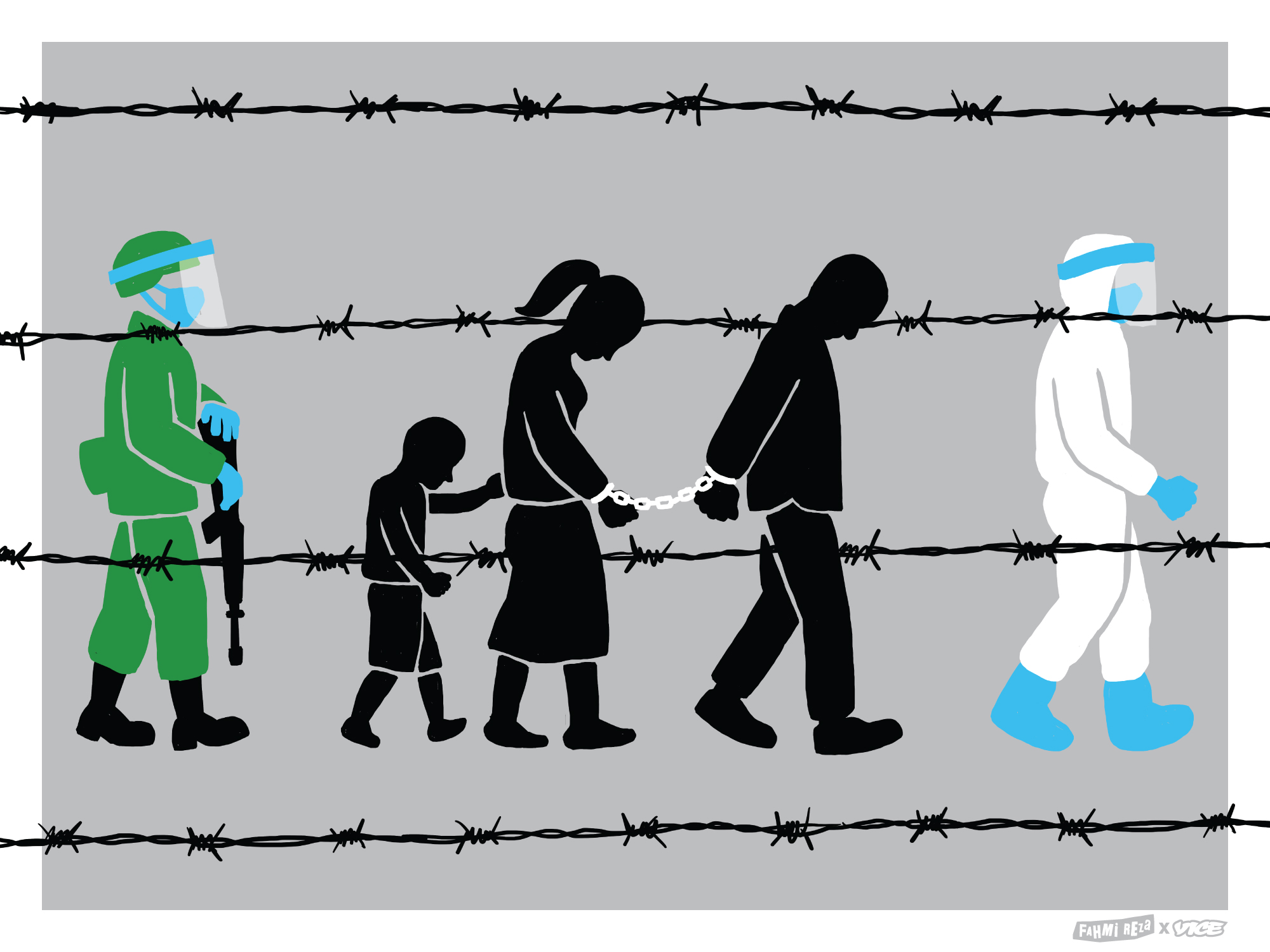

Just as the country came out of lockdown, unsettling images of government-sanctioned raids on “undocumented and illegal” migrant workers and refugees hit the internet in May, some with children as young as four.

Rounded up near markets and lodging facilities outside Kuala Lumpur, thousands were escorted by armed officers and loaded onto trucks and transported to overcrowded detention centers. “We were being caged,” a Rohingya refugee who fled Myanmar for the safety of Malaysia said back then. The raids alarmed and angered the UN and other human rights groups around the world but the government said in its defense that it was to curb the risk of further COVID infection.

The pandemic began to expose widening inequalities and treatment among vulnerable groups in society.

And little did rights groups know that it was only a sign of much more troubling issues to come later in the year.

For the month of June, it was a plucky teenager from the state of Sabah who captured national interest and dominated headlines after she climbed a tree to study and sit for online exams, a strong protest against poor internet connection and accessibility in sprawling East Malaysia that went viral.

Veveonah Mosibin, an 18-year-old from the village of Kampung Sapatalang, gained fans and fame from her brilliant videos on YouTube showcasing her rural life. But at the same time, she also found enemies in older, male politicians who belittled her and slammed her efforts as “dramatic” and “attention-seeking.”

By the time July rolled round, the MCO lockdown had ended and Malaysians were re-adjusting to life. Many were eagerly anticipating the first (of five) verdicts of the high-profile 1MDB trial involving former prime minister Najib Razak.

Najib, once considered the most powerful man in Malaysia, was found guilty of all charges of corruption, money laundering, abuse of power and criminal breach of trust and was handed a 12-year jail sentence. Unsurprisingly, he has condemned the court decision and maintains his innocence, controversially remaining free pending the outcome of an appeal.

Opposition politicians and global observers who spoke to VICE World News welcomed the landmark ruling as a test of the country’s rule of law, which had come under serious scrutiny during Najib’s nine-year reign.

But to many Malaysians who had suffered over the years as a result of Najib’s leadership, blatant corruption and cronyism was still a deep-rooted problem in the country, one that would likely remain unresolved for years. “While Najib’s verdict was well-deserved, it is also important to understand that the rot goes far deeper than one man. Graft is deep-rooted in society. Many Malaysians have grown used to paying bribes to get things done,” wrote Cynthia Gabriel, founder of the Center to Combat Corruption and Cronyism in an op-ed piece published by Al Jazeera.

Gabriel had shared her personal experience in being harassed over her role as a civil society activist uncovering government graft.

To others, another crucial piece of the 1MDB puzzle remained: the whereabouts of one man, regarded by many as being the true mastermind of the saga, notorious Malaysian Chinese fugitive businessman Jho Low. He remains at large and has evaded investigations.

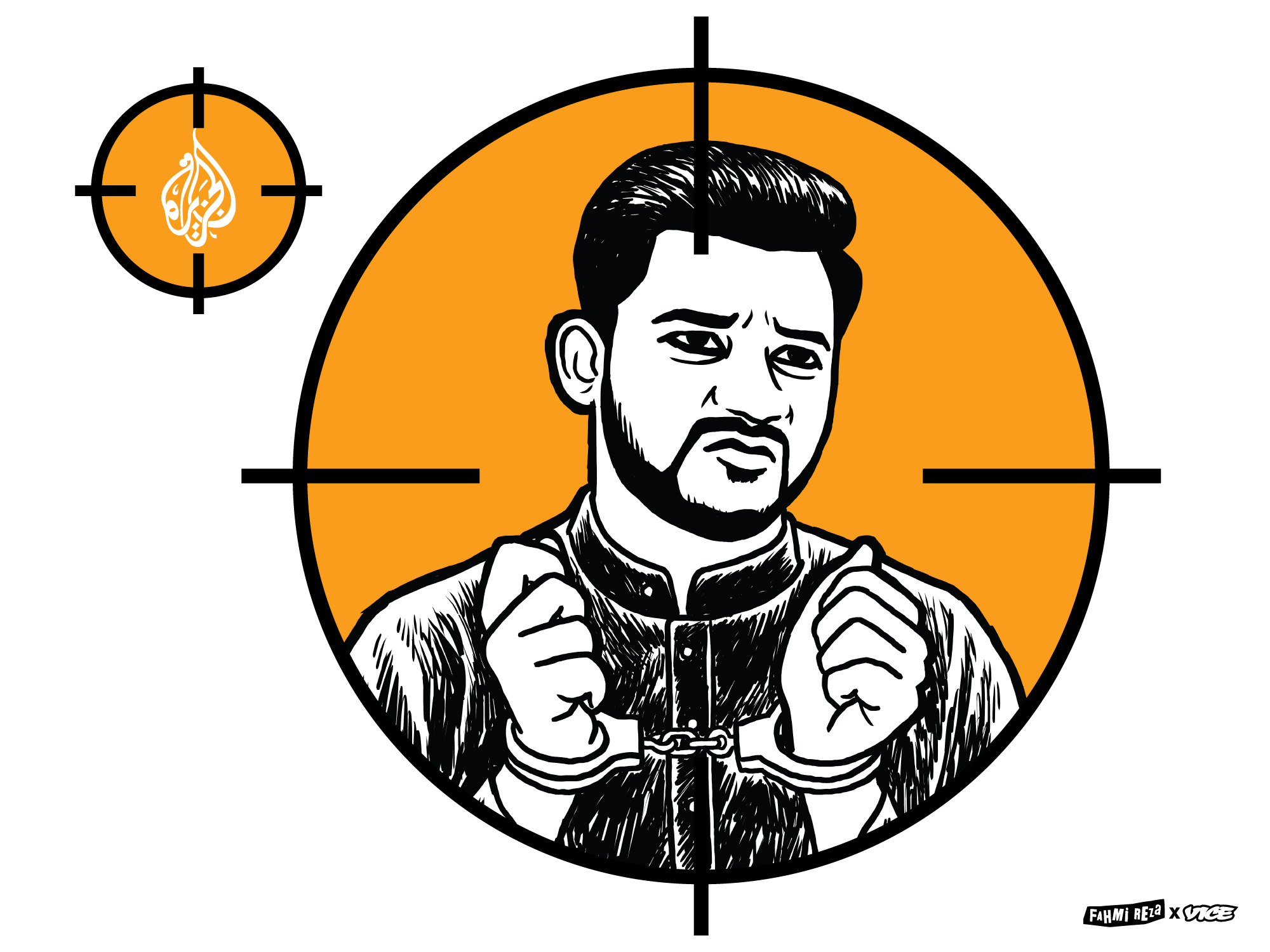

When it comes to bad news, the messenger is always punished.

This certainly proved to be the case in August when Malaysian police raided Al-Jazeera’s Kuala Lumpur newsroom and offices in response to a controversial investigative documentary about the treatment of migrant workers and refugees in the country during the MCO lockdown in May.

The move was slammed as an attack on press freedom in Malaysia.

The Qatari-backed media network fiercely defended its journalism. The man at the center of the controversy, a Bangladeshi whistleblower worker named Mohammad Rayhan Kabir, was arrested by the immigration department and expelled for criticizing the Malaysian government. “This Bangladeshi national will be deported and blacklisted from entering Malaysia forever,” the immigration ministry said in a statement at the time.

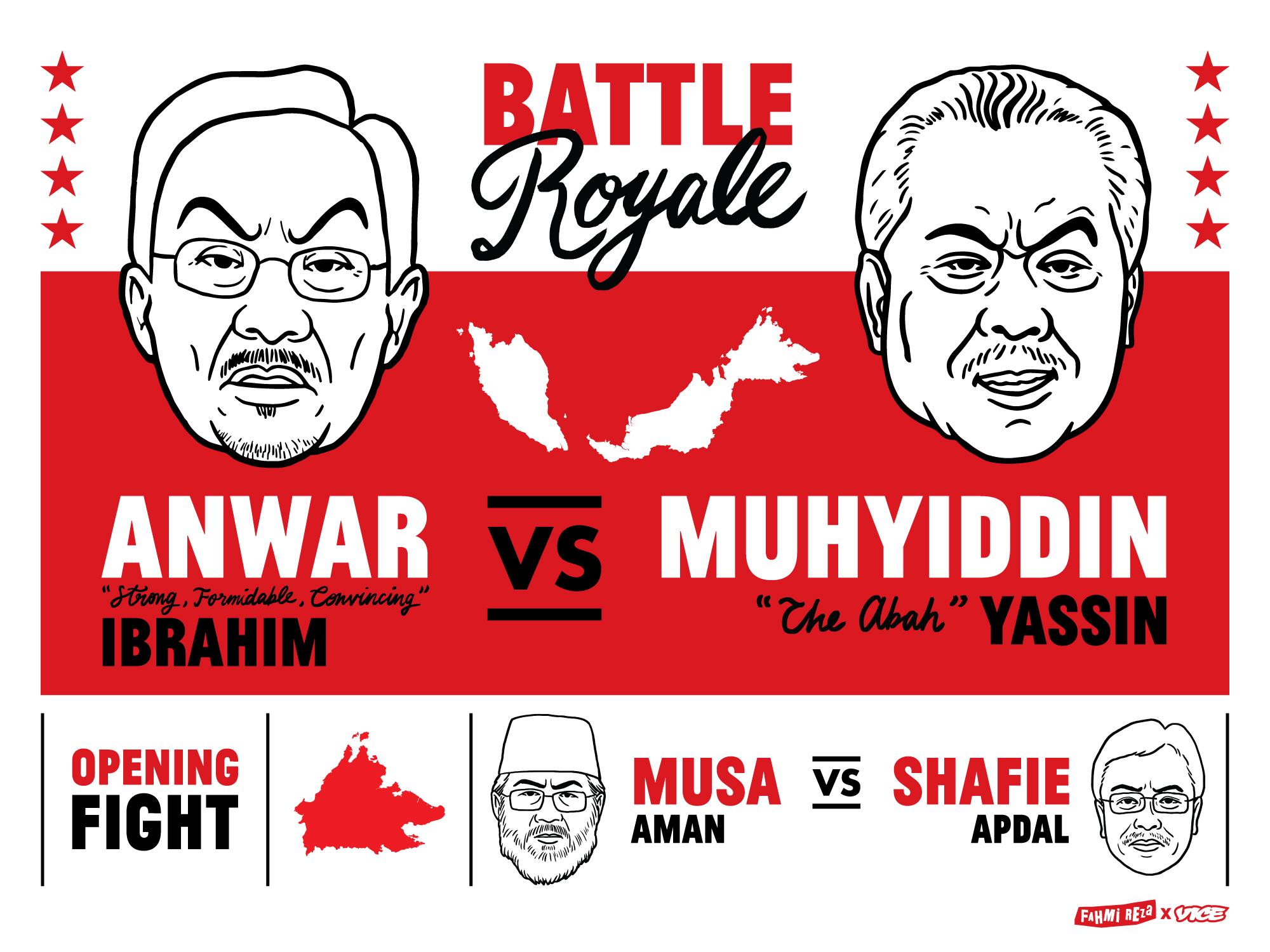

After months under the pandemic, Malaysians in September saw the re-emergence of opposition leader Anwar Ibrahim, who came out swinging with a stunning claim that he had successfully secured a majority in parliament to form a new government and oust the embattled leader Muhyiddin Yassin.

We won’t go into too much detail about Anwar’s ambitions of becoming prime minister but his attempts, unsurprisingly refuted by Muhyiddin, led to weeks of several tussles between the two.

Malaysia’s Al-Sultan Abdullah eventually stepped in and served up a royal intervention but not even the king could have foreseen an ill-fated by-election which went ahead in the East Malaysia state of Sabah, seen by critics as an attempted boost for the embattled Muhyiddin.

The campaigning period, followed by the weekend election, saw local politicians mingling freely with voters and amongst themselves, all while disregarding social distancing measures. The result was a slim victory for Muhyiddin but a blow for the rest of Malaysia which saw daily virus spikes into the thousands.

Looking back, Muhyiddin admits that the Sabah state polls contributed to a later wave of infection.

But the incident hit at something that many Malaysians have been saying about their leaders all along; that their political ambitions outweighed public needs.

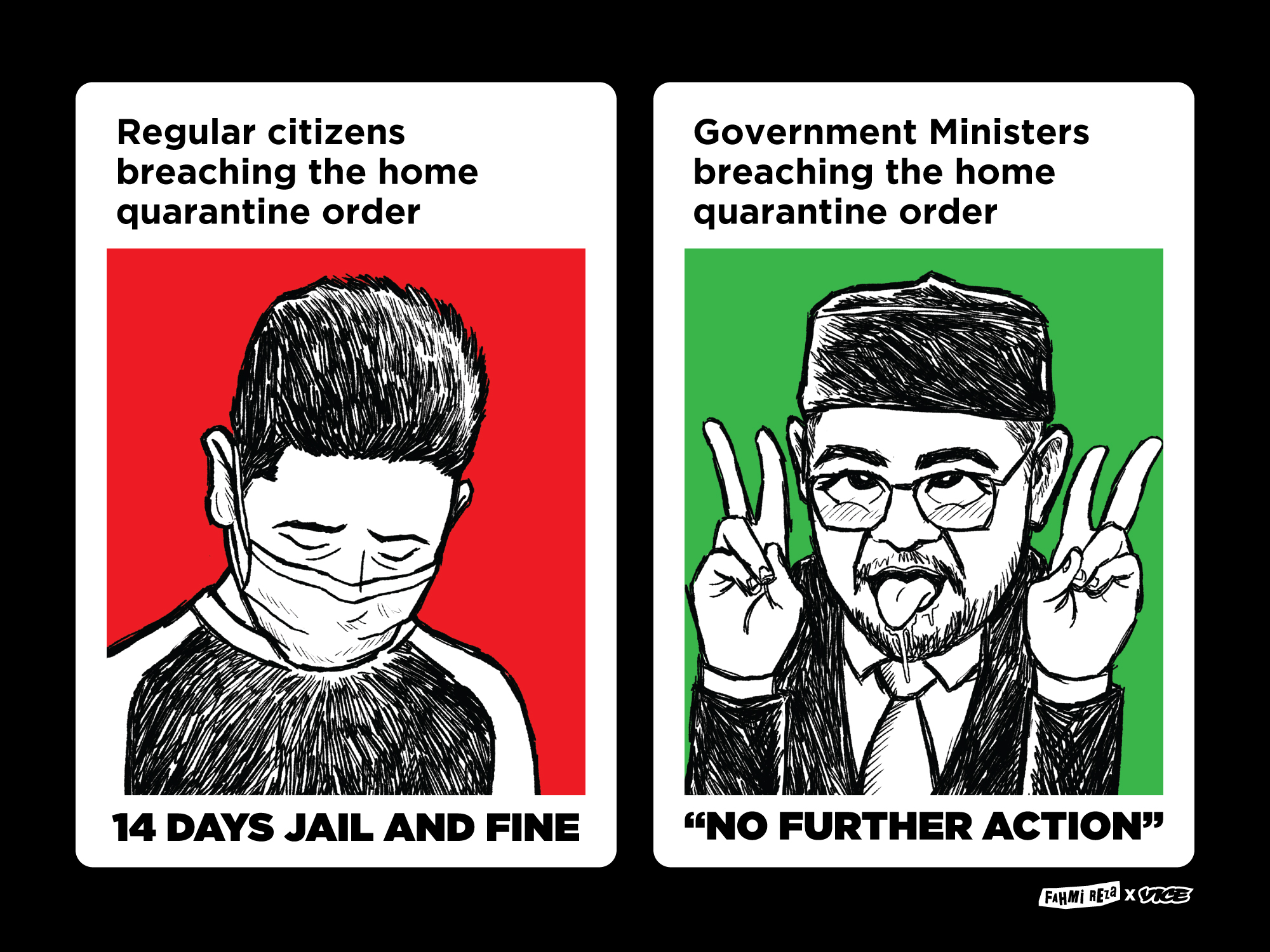

Official rules state that every person entering Malaysia is subject to a mandatory 14-day quarantine period. But a high-ranking cabinet minister, who drew public fury for skipping quarantine after returning from a trip to Turkey earlier in the year, was allowed to walk away scot-free despite blatantly breaking the rules.

On Oct. 22, the Attorney-General's Chambers ruled that “no further action” would be taken against Khairuddin Aman Razali from the Malaysian Islamic Party due to “insufficient evidence”. Khairuddin issued a public apology and said that he paid a fine of RM 1,000 and would forgo his ministerial salary as a “show of remorse.” But that wasn’t good enough for angry Malaysians who called the government out for blatant double standards and reiterated that no one in the country should be above the law.

Case in point: several recent cases involving ordinary citizens being sent to jail or slapped with far heavier fines for violating similar quarantine rules and regulations.

The pandemic exposed persistent inequality in almost every country, with the most vulnerable in society being discriminated against. Neighboring Singapore, which was once lauded for its successful containment of the virus, saw its success crumble when tens of thousands from its migrant worker community became infected.

In November, that narrative was repeated and magnified in Malaysia when the virus reached the factories and foreign worker dormitories of the world’s largest medical glove maker, Top Glove.

Workers forced to work overtime to pump out rubber gloves and other protective healthware while living in cramped and overly crowded dormitories. Many even complained about health test results being withheld from them as the virus continued to spread.

Migrant rights activists noted the irony of the situation, which has since become dire: the world’s biggest rubber glove manufacturer exporting essential supplies and profiting in times of crisis, but failing to protect their own frontline workers from the virus, with more than 5,000 now infected and one death.

Top Glove has fiercely denied continuous allegations of substandard labor conditions in its factories across Malaysia, reaffirming its commitment to the health and safety of its workers and maintaining its compliance in following standard operating procedures laid out in government Covid-19 guidelines.

2020 is finally coming to an end, wrapping up another chaotic and colorful year in Malaysia.

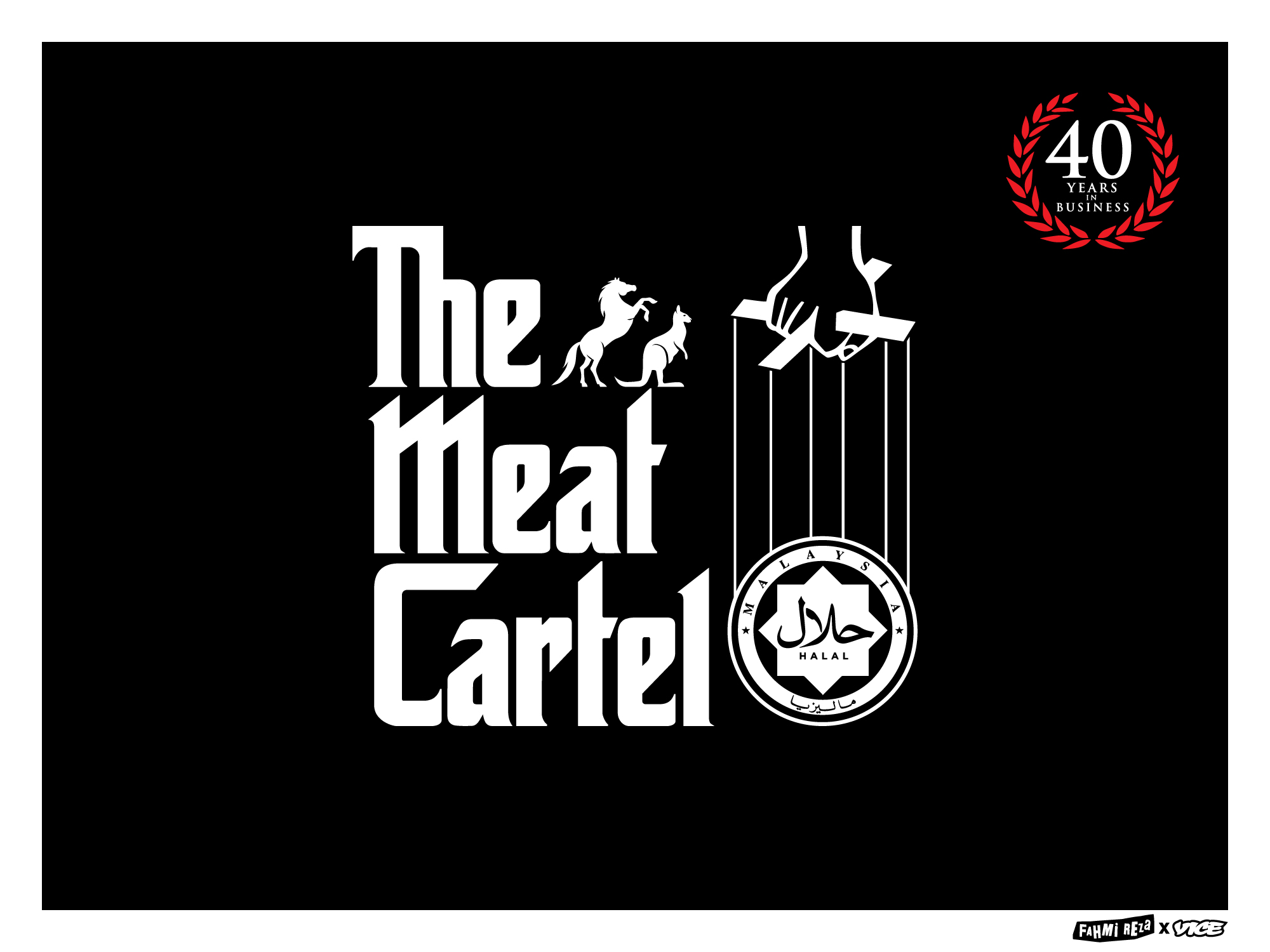

But another shocking scandal emerged in December concerning several government agencies accused of supplying fake halal meat for public consumption, a highly-sensitive and polarized issue in the Muslim-majority country.

Dubbed “the meat cartel,” local media outlets exposed the criminal ring, believed to have been in operation for over 40 years, alleging it passed off kangaroo, horse and beef products as halal and forged religious certification documents. Officials on the ground were also believed to have taken bribes and payouts over the years.

The news was hardly surprising and sadly lost on many in the country, still suffering from prolonged political fatigue given the back-to-back events which have occured.

With a new and more infectious strain slowly spreading across the world, it’s safe to say that in 2021, Malaysia will be continuing its ongoing fight against the coronavirus.

The government has also promised a proper general election once the pandemic is over.

But until then, Muhyiddin Yassin and his ruling government will play a crucial role in getting Malaysians through this current tough fight. And only time will tell if the country will get back on the right track.