In Photos: The Disfigured Urban Landscape of Hong Kong

December 24, 2020In 2020, Hong Kong as we knew it ended with a whimper, muffled by a pandemic.

Citing public health concerns, the Beijing-backed local government banned demonstrations. For the first time in 30 years, an annual vigil on June 4 commemorating the anniversary of the bloody Tiananmen Square crackdown was prohibited in the semi-autonomous Chinese territory, although thousands defied the ban and turned up anyway.

Later that month, Beijing imposed a new national security law on the city that further chilled dissent—or, at least, the expression of it. The law empowers police in Hong Kong to arrest people over actions and comments deemed threatening to the security of the world’s No. 2 superpower, such as tweets calling on foreign governments to sanction Chinese officials. The maximum penalty is life in prison.

Instead of demonstrating in the streets, the city’s pro-democracy activists spent the better part of 2020 holed up at home, where they seethed and wailed as they woke each day to news of the arrests, imprisonments and exile of their peers.

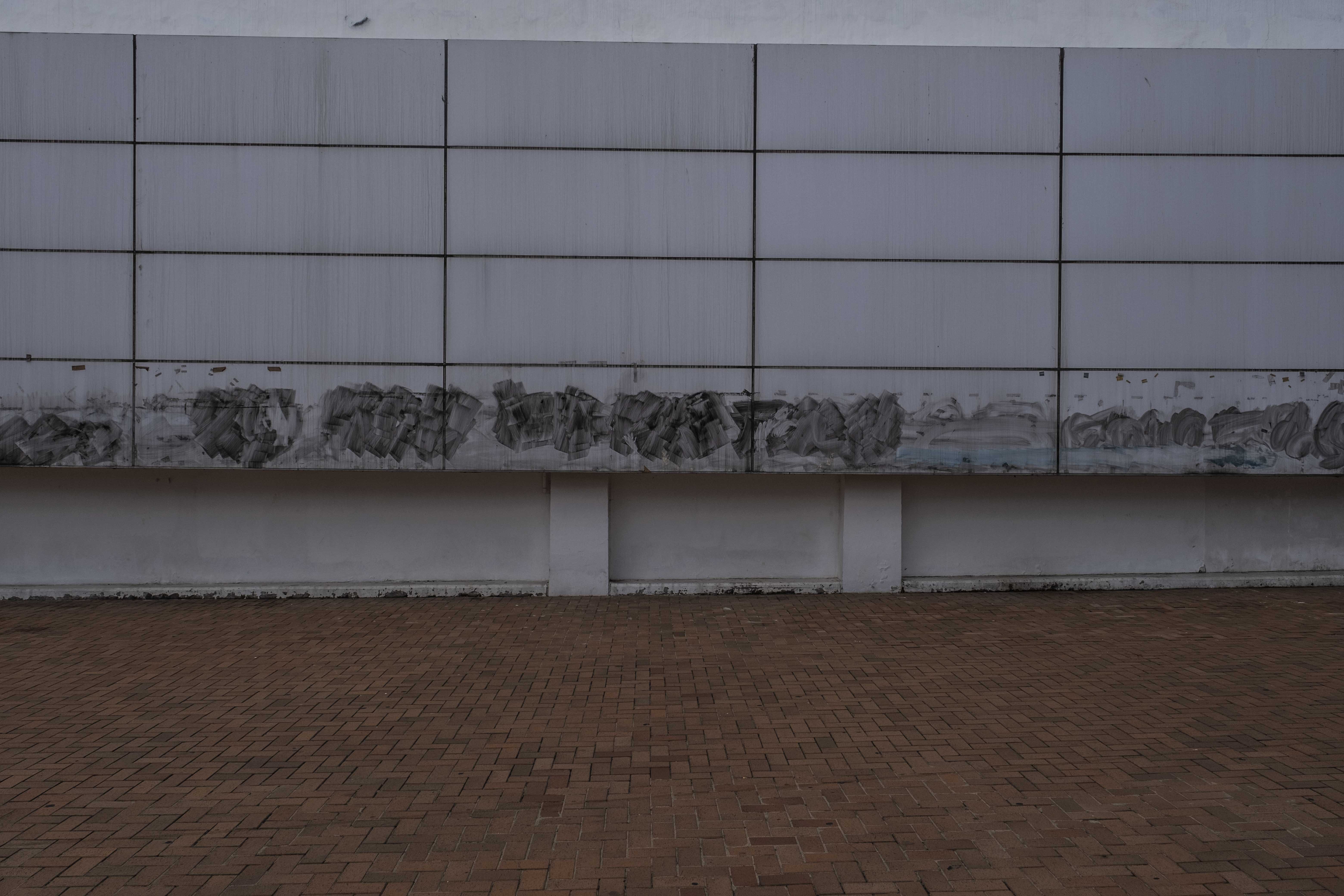

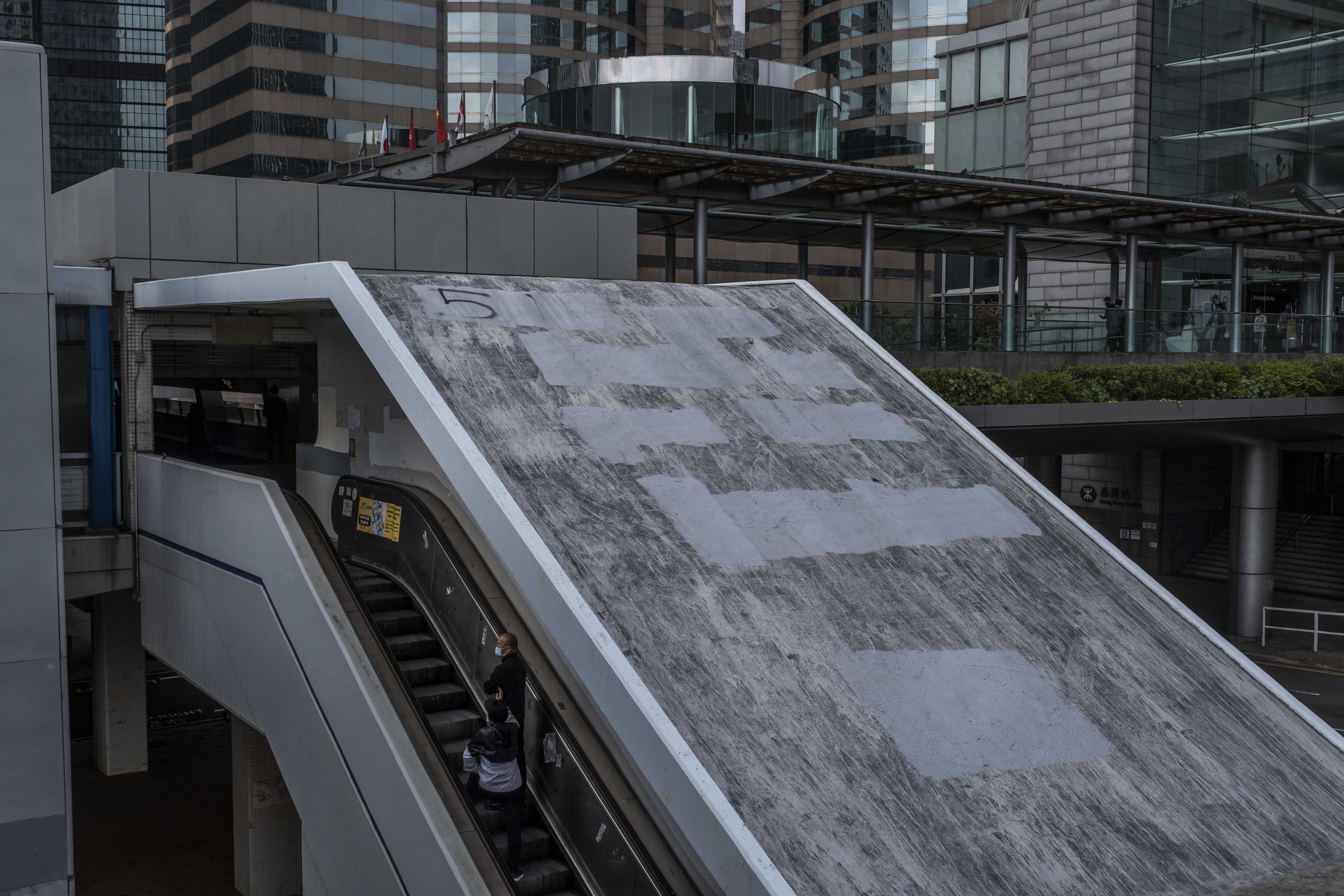

But if Beijing and its Hong Kong loyalists take solace in the chilling effect of the law, the disfigured streets of the city serve as a symbol of both their crackdown on dissent and the popular resentment simmering beneath the surface, ready to erupt at a moment’s notice as it did in 2019.

In the aftermath of the 2019 anti-government unrest, the local authorities altered the landscape of Hong Kong, turning footbridges into cages, covering traffic lights with metal grilles and reinforcing electrical boxes.

Hong Kong protesters in 2019 paralyzed traffic to pressure the government to address their demands for better police accountability and greater democracy, blocking streets and breaking signal devices to disrupt the flow of vehicles.

But the scars of the protests are mere symptoms of Hong Kong's political ills. What the government’s fortification does not address are the underlying anger and fears that fueled the largest demonstrations the former British colony had ever seen since it returned to Chinese rule in 1997, under the promise of a high degree of autonomy and wide-ranging freedoms.

The 2019 protests began in opposition to a now-withdrawn proposal to allow extraditions to mainland China due to concerns that it would blur the line between Hong Kong, which has an independent judiciary, and the mainland, where judges are ultimately loyal to the ruling Communist Party.

Those concerns added to long-running fears of eroding freedoms as economic integration with the mainland continued apace. The disenchantment with the central Chinese government runs especially deep among the city’s youth, some of whom see independence as the only path to achieve genuine democracy.

Violence flared, with scenes of clashes between protesters and police dominating front pages for months.

The destructions have left marks even in the city’s upscale malls, where glass panels shattered by activists are replaced by metal railings. They are a visual reminder of how businesses were caught up in the political turmoil as some activists vandalized shops and properties perceived to support Beijing or the Hong Kong authorities.

Now, with leading activists jailed and opposition politicians barred from office, Hong Kong’s pro-democracy movement appears to be sputtering, just as it did in the few years after the 2014 Umbrella Movement failed to result in freer elections of the city’s leader.

The relentless assault on the democracy movement has prompted talks of another wave of mass migration from Hong Kong after thousands fled the city in the wake of the 1989 Tiananmen crackdown.

The new national security law has raised the price of dissent and may have deterred some. But the 2019 protests demonstrated just how quickly a flagging movement could reignite, so long as the cause of dissent is left untreated.