India Is Losing Its Children to Abandoned ‘Killer Wells’

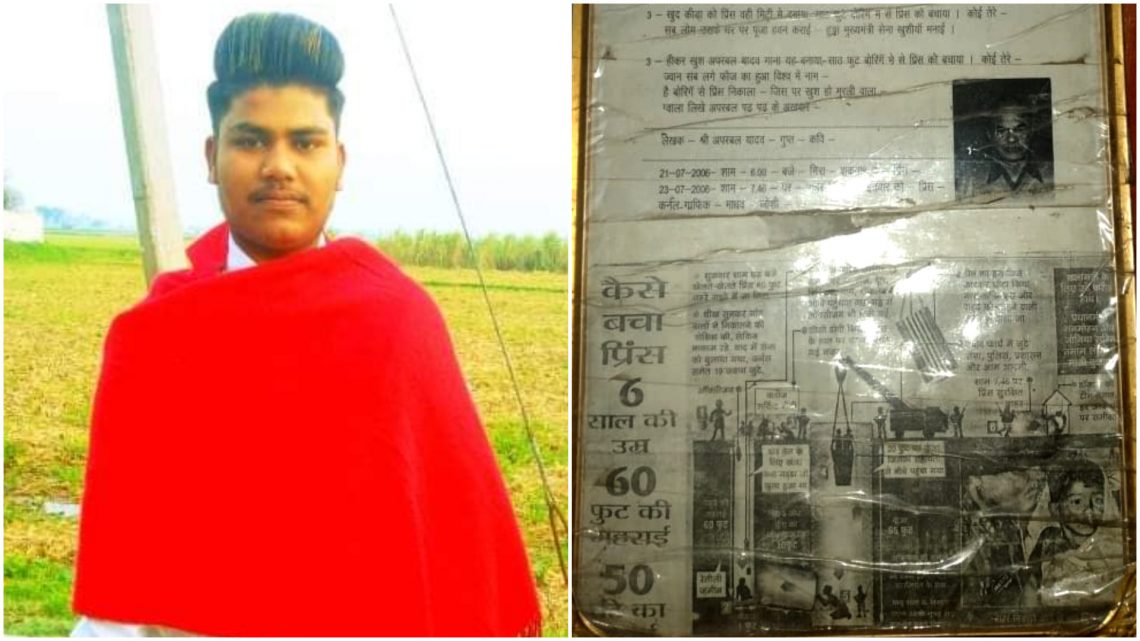

November 13, 2020Prince Kumar, a resident of the northern Indian state of Haryana, was just four years old when he attained a kind of fame he had never imagined. "Many kids must have gone through it too, but I caught the attention of the media like never before," Kumar, who is now 18, told VICE News.

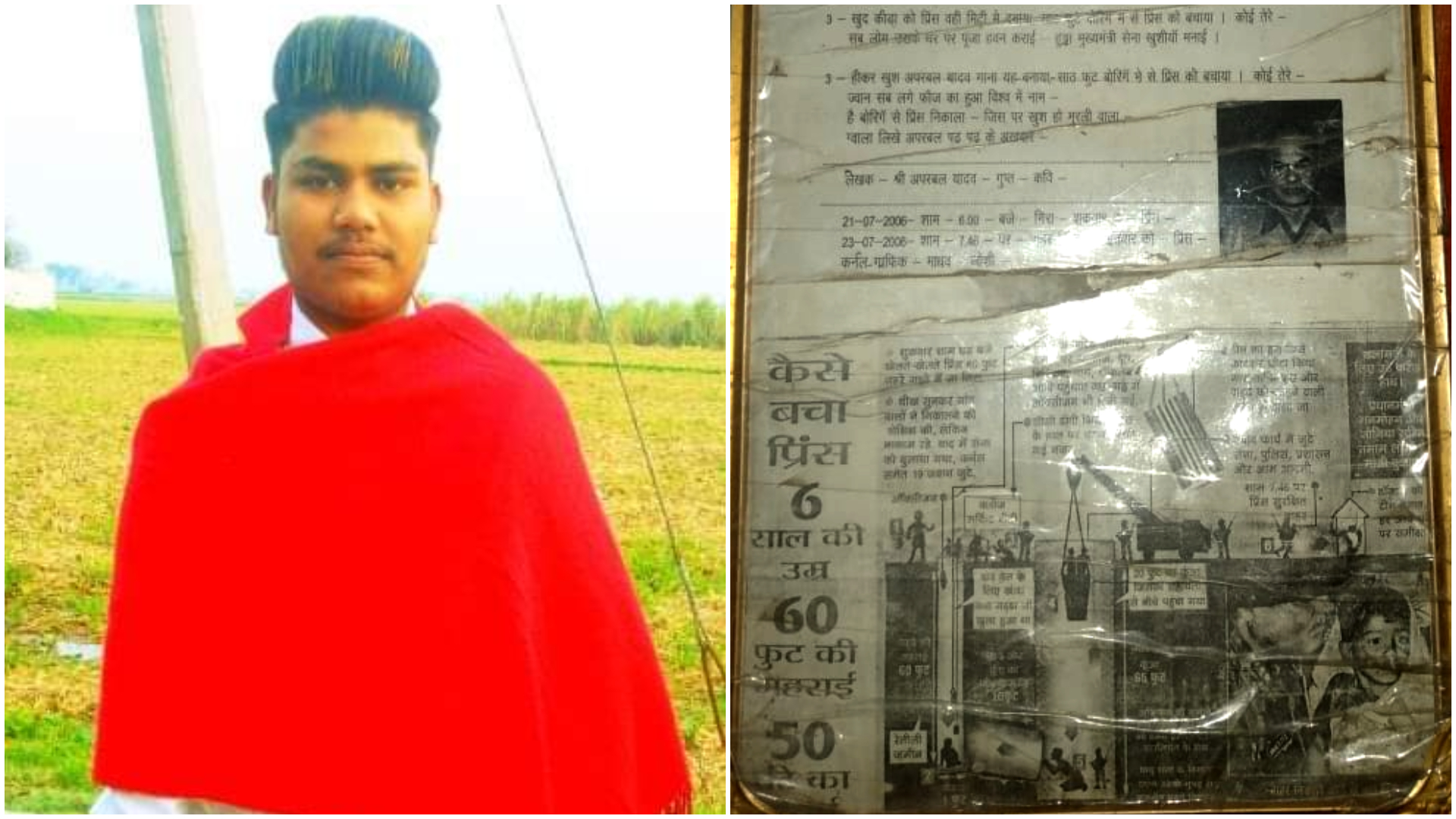

In 2006, Kumar fell into a 60-foot borewell—a deep, narrow hole drilled into the ground to source water—in his village. For 48 straight hours, Indian television channels flashed gritty visuals of a rescue operation by the Indian Army, in which officials tried to save Kumar through a tunnel dug from an adjoining well. He was stuck within a space of barely two-and-a-half feet.

"I thought I was done for," Kumar said.

Several people, including the then chief minister of the state, Bhupinder Singh Hooda, had camped in the village to keep track of the mission. When this son of a daily wage labourer finally surfaced from the hole, the country rejoiced. Some media outlets labelled him "the borewell boy" and the government even announced an award for Kumar and the village.

"In fact, it was my birthday the day I fell. I was on my way to the market when I fell in the hole that was covered by a sandbag," Kumar said. "After the rescue, I was in the hospital and everyone came in to celebrate my birthday."

Kumar's story might seem original, but in reality, India's "killer wells" are a common problem. In fact, the highly publicized rescue operation was rare for being successful. Not everyone makes it out alive.

India is the biggest user of groundwater in the world, according to government statistics. There are roughly 27 million borewells across the country of 1.3 billion people. But the increasing number of accidents prove that many of them are defunct, abandoned and accidents waiting to happen. Almost all who fall into borewells are children because of the narrow width of the opening. Data also shows that an average of 70 percent of child rescue operations fail.

The latest incident took place just last week when a three-year-old boy fell into a 200-foot well in the central Indian state of Madhya Pradesh. It took the rescue team 90 hours to dig him out. By then, he had died. Last year, two-year-old Fatehveer Singh fell inside a 150-foot well in the northern Indian state of Punjab. It took 109 hours to get him out. He didn't make it either, and his death triggered protests.

In another famous case from the south Indian state of Tamil Nadu last year, two-year-old Sujith Wilson was retrieved from a borewell in a decomposed, dismembered state after 82 hours.

Official data shows that over 40 children have fallen into borewells since 2009. That number might just be the tip of the iceberg, especially in rural pockets where there are no local disaster response teams.

"The frequency of these incidents is more than an average of five to six incidents per month," Randeep Kumar Rana, Deputy Inspector General of National Disaster Response Force's north-west sector, told VICE News. "In some states, borewell deaths are increasing every year."

It's also difficult to pin the blame on anyone when tragedy strikes. Borewells, with depths varying between 100 feet and 1,500 feet, are dug for agrarian or irrigation purposes. Many are dug without official permission in places facing water shortages.

Chennai-based hydrologist J Saravanan told VICE News that India lacks standard regulatory guidelines on digging wells for individuals and farmers. "If a farmer has to dig a hole in his backyard, he can go ahead and do it. He does not need any clearance from any authority," he said.

There are also many instances of illegal borewells dug up by "mafia-style" groups, builders or landlords. Local authorities in some parts of India have been busting the "water mafia" for illegal borewells and supplying overpriced drinking water. Illegal borewells are also considered one of the major reasons behind the fast-depleting groundwater in water-scarce urban areas.

Haryana—where Prince Kumar's accident occurred—has a severe water crisis because of depleted groundwater. There are "overexploited" zones where pumping underground water exceeds what's available. Saravanan said in many cases, individuals remove the cast iron cover and pull out the PVC pipe once the borewell is all used up. This bare hole, sometimes carelessly covered by flimsy material, like Kumar's case, becomes a fatal playground.

In 2010, the Supreme Court had issued guidelines to state governments to take care of abandoned, under-repair or newly constructed borewells to prevent fatal accidents. The guidelines included the need to fence the holes as well. But implementation on-ground is inconsistent. Last year, after two-year-old Sujith Wilson’s death, a court blasted the state government when asking whether they need a corpse to act on the problem.

Rana said that children falling into wells is not considered a disaster, according to the National Disaster Response Force’s mandate. “But since saving lives are involved, we respond,” he said. “We also have the limitations of not having local units, where most incidents actually happen.” Rescue operations are also extremely dangerous.

"There should be a local service for incidents like this, just like we have fire service," Rana said.

Some experts feel that the onus on the closure of abandoned wells should be on the local authorities, not the ones who dig them. "All we need is one regulation that says that if a borewell is no longer in use, it needs to be sealed with a proper lid. Everything ends there. If you do a survey only after the incident happens, what’s the point then?" said Saravanan.

Rana, however, said that it's difficult to hold anyone accountable. "The borewells are dug by individuals. They're the diggers, they're the victims," he said. "There's a lack of awareness."

Despite endless accidents and deaths, reports on newer incidents still conjure up the valiant efforts from 14 years ago with Prince Kumar. But the ending is not happy for most of the children.

"When I see a child dying after falling into these wells, I feel very bad. I've been strongly voicing that these holes should be closed up. But that has not happened," said Kumar. "When I finish my studies, I want to join the Indian Army, so that I can also save lives, the way mine was."

Follow Pallavi Pundir on Twitter.