She Was Separated From Her Twin. Now She’s on a Mission to Separate Others

November 12, 2020In 1999, the birth of twin girls to a woman in Goiânia very briefly captured Brazil’s attention. Not because the mother was famous, but because her daughters were born alive. Larissa and Lorraine Gonçalves were born conjoined at the hips, sharing three legs and with their livers, bladders and small and large intestines melded together.

The media referred to the duo as “Larissa and Lorraine, the Siamese twins”, and they were adopted by their aunt, Luciana. For the first year, Luciana cared for the girls, which was hard as she didn’t have much money. Lorraine had been diagnosed with cerebral palsy at birth, and often needed hospitalization that was invariably expensive.

Life was hard, but there didn’t seem to be any options. At one stage the family was contacted by a famous American surgeon who offered to separate the twins at a cost of US $1.2 million. There was no way Luciana could raise that kind of cash. But the offer gave her an idea.

When Larissa and Lorraine turned one, Luciana contacted the producers of a local TV station to see if they wanted to feature the twins. The producers agreed, and Luciana used the platform to ask the public to help finance the family’s medical expenses. It was a very analogue form of crowdfunding, but it worked: a Brazilian pediatric surgeon saw the broadcast and offered to separate the girls for free. The only hitch was that he’d never actually tried the procedure—but he said he was confident.

The twins went into surgery a few months later. After an operation that took 10 hours and enlisted the help of 58 medical staff, they were successfully separated. As Larissa explained, “My sister and I were again featured [in] the headlines but this time, as the conjoined sisters who got separated and survived”.

Today Larissa Gonçalves is 21. She lives in a small city called Santo Antônio de Goiás, around three hours from the national capital of Brasília. And it’s here that she’s now studying to become a pediatric surgeon, in the hope of specializing in separating conjoined twins, just like the surgeon who separated her.

“If I’m alive today, it’s because of medicine’s latest advances,” says Larissa.

Her sister, Lorraine, wasn’t so fortunate. She died at the age of seven from complications relating to her cerebral palsy.

“Unfortunately I don’t remember my sister very well,” Larissa says, explaining that she was simply too young to have a clear recollection. “Although, it may sound like a cliché, but I still feel connected to her.”

Now Larissa feels she needs to somehow honour all the years she got that her sister didn’t—or in some small way give something back to the people who kept her alive.

“I feel lucky for being born and then adopted by someone who loves me,” she says. “My goal is to celebrate life, no matter the circumstances, and I hope that medicine will allow me to help other people to celebrate their lives too.”

The doctor who performed Larissa’s surgery is a man by the name of Zacharias Calil. Now at 66, he’s subsequently performed 18 similar separations for conjoined twins in public hospitals for free—a run that gained him a Nobel Prize nomination for medicine in 2020.

Dr Calil’s parents were born in Syria, but he was born and raised in Brazil. He speaks into the phone patiently, like an adult trying to explain something complicated to a child.

“I knew that I was going to be a surgeon since I was a little boy,” he says in that slow, calm voice. “I was obsessed with anatomy books and TV shows about medicine. What I never expect is that I would be splitting conjoined twins in the future. How do I feel about that? Lucky, of course. I love my job.”

Dr Calil explains that it’s still largely unknown why some twins fail to separate in the womb. What we do know is that, for whatever reason, some fertilized eggs begin to divide around the 13th day of pregnancy. The vast majority manage to divide successfully, resulting in healthy identical twins, but some remain partially connected and as a result, develop as conjoined twins.

Roughly one in 150,000 babies are born conjoined, and in 75 percent of cases the twins die in the first 24 hours of life from various organ deformities. Even among the small subset of survivors though, not all are able to undergo separation surgery as they often share brains or hearts.

“Each case is unique, for each has a different anatomy, and we’ll never witness a case similar to the other,” explains Dr Calil.

Globally speaking, the survival rate for conjoined twins post-surgery is about 20 percent, but Dr Calil says his team has managed to raise that rate to around 50 percent simply by maintaining the same team of people working together for 20 years. His team includes pediatric surgeons, plastic surgeons, orthopedists, anaesthesiologists, cardiac surgeons, pediatric urologists, nurses, nurse technicians, scrub nurses and lab technicians.

Another reason Dr Calil maintains that his team has been so successful is their use of detailed models to train on. He says these first came about in 2013, when he found a company in Italy that manufactured human models, rendered in resin, that allowed his staff to train on all the stages of a separation surgery.

According to Dr Calil, conjoined twins can only be separated from about one year after birth. By that time, babies are heavier and are able to more reliably withstand surgical intervention.

When asked if he thinks separation surgery could be improved with robots, or even automated, he balks, explaining that he thinks the humanization of medicine is the true goal.

“We often imagine robots performing surgeries, but the future of medicine truly lies in humanizing the service offered to the patients and investing in the team of professionals that are highly qualified in their fields,” he says. “Even though technological evolution seems to be essential, nothing would be possible if it weren’t for the experience of those professionals”.

His belief in people also underpins his relationships with his former patients. Dr Calil says he maintains a close relationship with all the children he’s separated, which means he still speaks regularly with Larissa. He even hopes to someday welcome her into his team.

“Larissa is such a clever girl and honestly I am very proud of her decision to help people who are passing through a similar experiences as her own,” says Dr Calil. “In my opinion, she will be the best type of doctor: one who truly cares about their patients and sees them as what they are—human beings who need to be treated with honesty, dignity and love”.

Larissa says that she and Dr Calil talk at least twice a year, every year. Once on the anniversary of her operation, and once on her birthday.

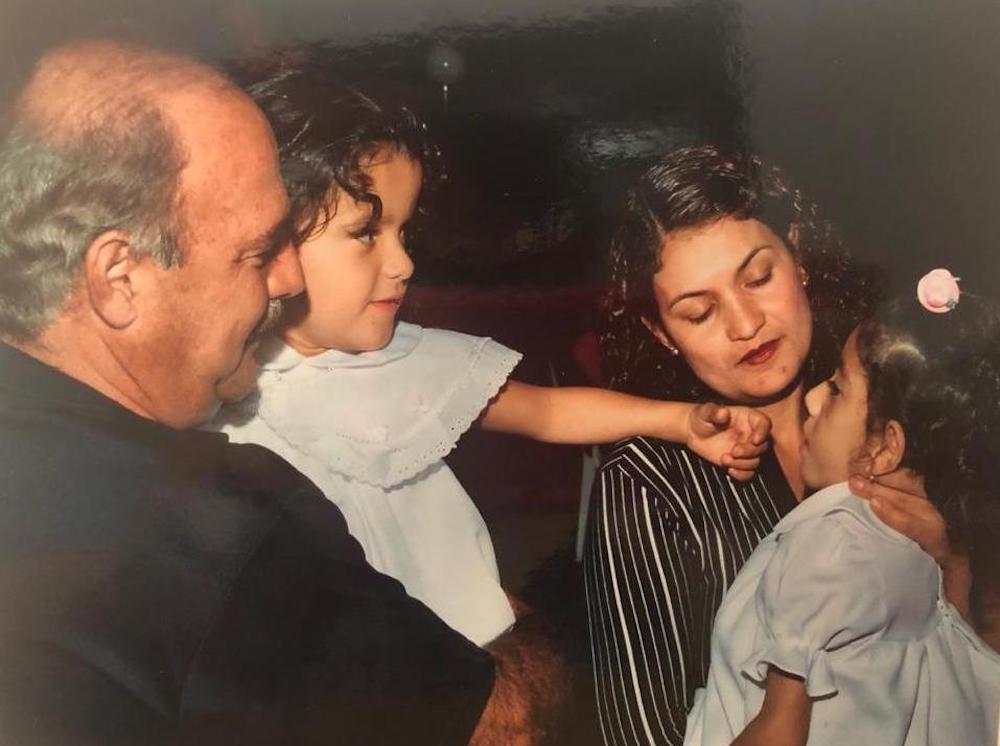

“One of my favorite photos is of him holding me in his arms and my mum holding Lorraine during our two-year-old anniversary party. I feel that from that day onwards he has always been cheering me on, not only as a doctor but also as a friend. To think that I could become part of his medical team makes me feel that my life has a purpose.”

For the past two years Larissa has been studying at home, hoping to be accepted to a public medicine school since she can’t afford a private one.

“Dr Calil taught me that anything is possible. And even though I don’t believe in meritocracy—because obviously a rich person has more of a chance of becoming a surgeon—I will do my very best to achieve what I want,” she says. “You can interview me in the future to ask me about my first separation surgery as a pediatric surgeon.”

Follow Felippe on Instagram