Twinning

October 30, 2020Twinning is this year’s annual Terraform Halloween short speculative fiction special from Geoff Manaugh. -The Eds.

OCTOBER 2022

The boat had been at sea for less than a week, drifting west with the currents, weathering squalls, never once floating close enough to other boats that their crews might notice something was wrong. Were it not for an early-autumn storm the previous evening, the ship might have traveled several more days, perhaps weeks, avoiding the island altogether, even colliding with debris in the open sea and sinking. In which case, everything that happened next would be quite different.

By the time the boat came aground, it was the end of October, well after prime tourist season was over. The nearest village had shut down nearly all its hotels and ferries had been cut to twice a week. There were still a few travelers on the island, loners and romantics hoping to experience a distant, lesser-known part of the archipelago, which explains why it was a young man from Canada, an aspiring photographer fresh out of college, who first spotted the boat and reported it to local authorities.

A ship had washed up on an isolated beach, the Canadian told them. Down on the south side of the island, where rock cliffs and sand faced the open waters of the Mediterranean. The boat was rolling back and forth in the waves, grinding up against the shore. It seemed pinned there, the Canadian said. Abandoned.

A shipwreck? The island’s police were instantly on edge. Competent seafaring went back generations here, where the outer edge of Europe hit the sea, and, for them, a wrecked boat was a wrecked conscience; it upset the order of things. Yet migrant boats had been washing ashore for years, they knew; perhaps this was another. Or could it be local? This worried them, admittedly more concerned for their own than they were for others. One man ran outside for a quick scan of the marina. Phone calls were made. There were no missing boats or crews.

The boat, the Canadian’s photos showed, was a small fishing vessel, modern but mastless, partially destroyed by fire. Dark, mounded shapes could be seen on deck, and though the Canadian’s images were excellent, taken with an expensive camera given to him just months before as a graduation gift, it was not at all clear what those forms really were. Large and hulking, they resembled dead livestock.

There’s something else, the Canadian said. He zoomed in, his finger pointing at the camera screen. Look.

Long reddish stains ran down the outer hull of the ship. They were everywhere, smeared and dripping. They looked like blood.

A small group of police and island fisherman—followed, to their frustration, by the Canadian, who maintained his distance but snapped photos the whole way—drove south, parked their vehicles, and climbed down over the rocks to the sand below.

The boat was exactly as it had been positioned in the Canadian’s photographs, half on sand, half on water, but the late-afternoon tide was rising. Within an hour, they knew, the ship would likely lift off and float back to sea; if the Canadian hadn’t come by when he did, perhaps no one would have found it at all.

The boat, they finally saw from the information on its hull, was from a town on Greek-controlled Cyprus. It had been fishing well outside its legal range, they realized, or it had been stolen; either way, the ship had wandered fully 300 miles from its city of origin.

Several men climbed aboard.

None of the early news reports were consistent with one another and none of them remained current for long. Details were both mixed and misreported, leading to rumor on top of rumor for at least the first forty-eight hours. What broke on local news, after one of the men phoned his wife in horror, describing what they had found on board amidst a chaos of tangled fishing nets and what appeared to be signs of an engine fire, was that a boat filled with corpses had washed ashore. The bodies were so deformed by fire, the man told his wife, that they seemed more animal than human. It must have been an inferno—which was strange, of course, because the ship itself was only partially damaged by flames.

The bodies aboard were all migrants, the first reports claimed, without evidence. Economic migrants desperate to reach Europe, killed in a tragic boat fire. It was an accident at sea. But arguments began immediately. No, others said, they weren’t migrants. They were war refugees. They had drifted over from Syria.

No, no, others disagreed. They were victims of human-trafficking—and this was no accident: everyone on board had been murdered. It was obvious, they said: the engine fire was deliberate. Some sort of cover-up. It must have been political.

It was Mossad. No, it was the Turks…

It was only when the men tried to move one of the bodies, the boat now rolling beneath their feet in the rising tide, that things took a turn for the worse.

No one had noticed this when they first climbed on deck because the bodies were so grotesquely disfigured—fused together, it seemed, in a blackened mass—but one man shouted. My God, he said, they’re doubles. Conjoined twins. The entire crew.

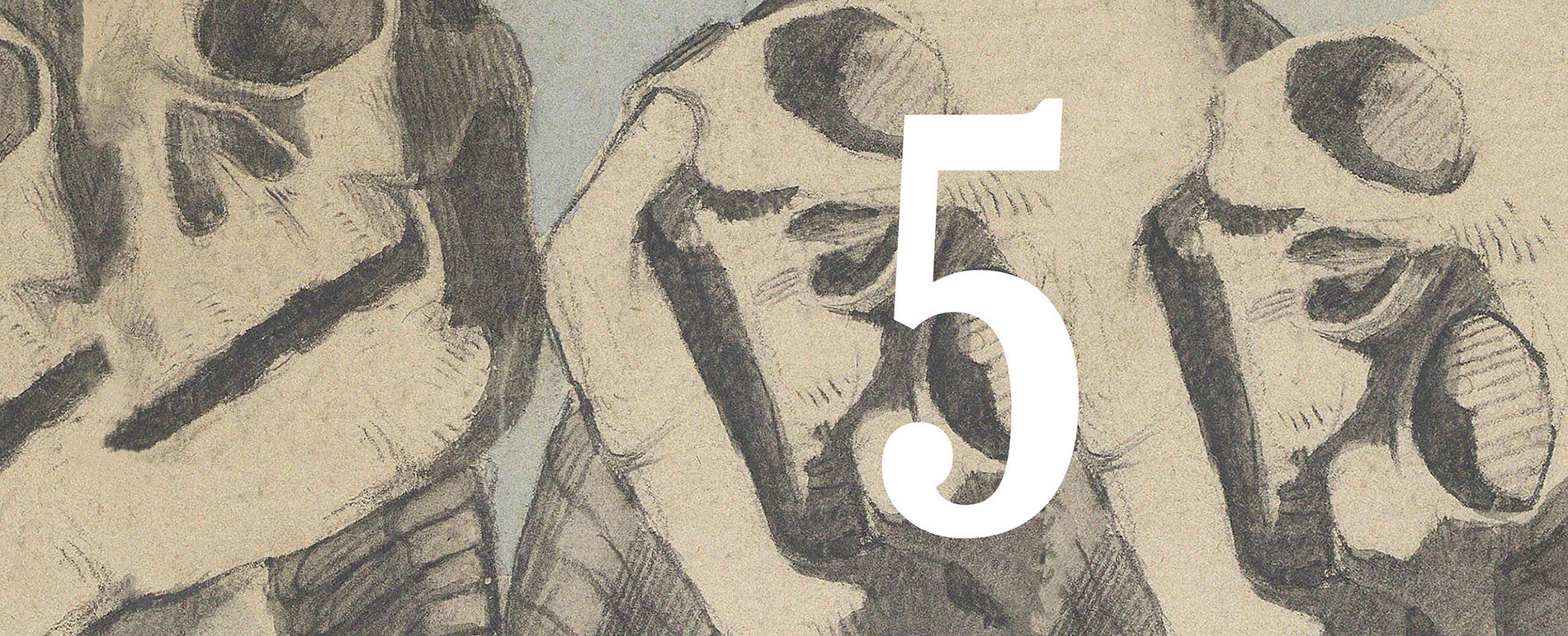

Five pairs of conjoined twins, connected not at the sternum, spine, or waist but everywhere, as if at random, merged at the arms, sharing legs, most of them horribly mis-sized as if joined with smaller versions of themselves, lying atop one another in charred knots.

Not five corpses, but ten; not ten corpses, but five.

In his photos, which eventually ran in newspapers and TV broadcasts all over the world, the Canadian managed to capture the scene in startling detail: the townsmen, their arms and clothes smudged with a charcoal of human flesh, looked pale, nauseated, some staring blank-eyed at the sea. One man, visibly shaken, his shirt covered in soot, leapt from the boat, stumbled up the beach, and vomited onto the rocks.

Word had traveled fast, the men saw, as they towed the boat into town. The sun had long since set. Dozens of villagers were out on the docks, watching, waiting. Several carried powerful marine flashlights, though most quietly tucked them away as the ship—sinister, unlit, dead against the night sky—floated into view, their desire to see replaced by unease.

The authorities’ original plan—to tie the boat up in the harbor and cover it with tarps—was clearly not an option. The smell of the fire, and of the bodies inside, was growing worse by the minute and a steady nighttime breeze meant it would have been anchored upwind from the village.

Then one of the men remembered something. Half a mile north of the town’s marina, his older brother owned a fishing warehouse. Modern, newly built, equipped with room-size refrigerators, it had been a recipient of European Union funding. The building had its own dock behind a repaired seawall that would shield the burned ship—and its scent—from the village. It seemed perfect.

Acting on orders from authorities, a small group of men worked into the night, gloved up, clad in aprons from their fishing boats, clearing the boat of corpses. It was horrific work. The bodies, where they weren’t blackened, had become gelatinous, the skin bursting and slipping until the only thing left to hold onto was bone.

They placed the bodies—five, ten; ten, five—down atop tarps inside refrigerated rooms that still smelled faintly of mackerel, swordfish, and squid.

Exhausted but sensing a market for his photos, the Canadian continued to shoot outside, well past midnight, capturing anything he could. Denied entry to the warehouse itself, he focused instead on a small group of men squatted aboard the burned ship, peering down at several canisters caught in the fishing net, one of which had burst, like a ruptured oxygen tank.

Within a day, before the Canadian’s photos of the boat became a global news sensation, while the islanders still had a modicum of privacy, the townsmen who boarded the ship that night began complaining of chills. Fevers and body aches. Their stomachs were cramping, some said, a terrible pressure rising beneath the breastbone.

One man said it was like he needed to cough something up, something painful growing inside him.

MAY 1995

The statue was large, but, because of its location, easy to miss. It had been mounted near an underlit wall in the furthest wing of the museum, in a side-gallery that most visitors chose to walk past without even noticing. That was a mistake: it was a wonderfully detailed piece, an utterly strange bit of architectural stonework taken from the nave of a German church, dating back to the 1400s. It rewarded sustained attention.

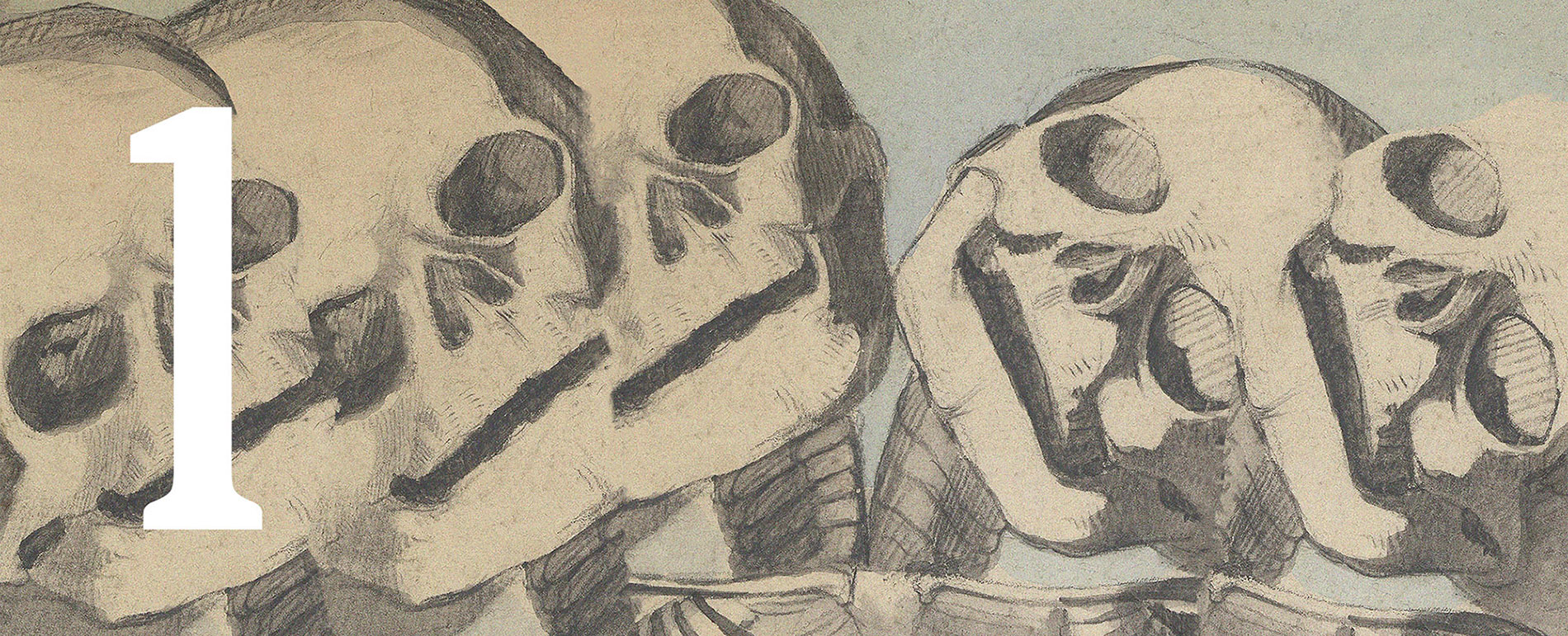

Exquisitely carved from a single piece of limestone, the statue depicted two human bodies wrapped around one another tightly, as if embracing. At first glance, the statue appeared identical to other ornamental pieces found inside a typical church of that era—but, upon further inspection, odd details began to emerge.

The two figures did not just share their legs, for example, but most of their chests and torsos. And they didn’t have four arms, oddly, but three—one of which appeared to be erupting from their mutual belly like an errant branch on an unkempt tree.

The second man’s face was also leaned back as if trying to sing; the face beside his, so close that they were cheek to cheek, appeared already lost in song. This gave the sculpture its unofficial German name, Die Gesangbrüder, the “Singing Brothers.”

Looking closer, however, in certain angles of light, an observant visitor would notice that the two brothers did not have entirely separate heads. Indeed, when the museum turned on its harsher lights—emergency lights it never used when visitors were still in the gallery—it became clear that the brothers’ mouths were not open because they are singing a carol. In fact, the brothers were not singing at all. Their mouths were open because they were in agony.

Sarah put her glass down, carefully. She was already on her second red wine of the evening and this sort of thing, she knew, would be noticed. Her department head, to Sarah’s right, was drinking nothing but water; her grant coordinator, also seated at the table, seemed nervously attuned to every detail of the evening.

Nevertheless, dinner had been going well, Sarah thought. She had been making small-talk, discussing her research, giving away minor but amusing details here and there about her personal life, and laughing whenever it felt appropriate. More importantly, she knew, it was nearly over. She had not embarrassed herself—yet—though the potential was always there. Lord knows she had done that before.

What really mattered was keeping her host, Dr. Christoph Kohl, happy, not making him regret having chosen her for this year’s Kohl Grant. The grant was given to just one student every academic year and was one of the most prestigious awards at the entire university—certainly one of the largest.

These dinners, held at Dr. Kohl’s house, a sprawling mansion in the suburbs west of the city, facing a lake, were required for every Kohl Grant recipient, but everyone knew they were just a formality, a favor of sorts for this retired surgeon, already in his 80s, too rich to know what to do with his money. But, Sarah suspected, the dinners were also a test. One mistake tonight, she thought, could risk it all.

Dr. Kohl’s fortune—as everyone knew, he was one of the most widely-profiled men in Minneapolis—came not just from his medical practice, where he had pioneered new surgical techniques that revolutionized how deformities of the spine could be treated; he was also heir to a vast family medical fortune.

The Kohl line of prosthetics, developed by Dr. Kohl’s grandfather in Germany after World War I, had become the global standard for prosthetic design and manufacturing; the licensing fees, contracts, and assorted dividends from family investments were rumored to bring Dr. Kohl, even today, as much as $30 million a year in passive income. That he would now be funding one of the most generous art history travel scholarships in the country—the Kohl Grant—would be surprising, were it not for his unusual upbringing.

The men of the Kohl family had always been interested in antiquity, he explained to his three guests, addressing Sarah in particular. His father had built a collection around pieces that worked as a kind of ironic—or, some critics might say, tasteless—commentary on the family business. Statues missing arms, legs, and heads, their limbs lost somewhere to the mists of history, had been exhibited around the Kohls’ house like advertisements for the prosthetics industry. They lurked on the edges of every room, marble figures tragically wounded, as if awaiting a state of completion. Many of those same statues, he said, now stood here in his lakeside home.

Sarah looked over Dr. Kohl’s shoulder as he spoke, at the stone form of a Greek warrior missing both its arms, its face hidden in shadow but turned directly toward her at the dinner. Slowly, so as not to seem distracted, Sarah glanced around the room and realized all the statues there, dozens of them, were turned this way, staring, broken and incomplete, keeping the surgeon’s guests under close watch. Unable to turn around, for fear of seeming paranoid or rude, she had the uncomfortable feeling that something was watching her from behind.

Dr. Kohl’s own art collection, he continued, had pursued similar themes. He had donated millions of dollars’ worth of artifacts to the university’s small but exceptional museum, and it was this same collection that now stood at the heart of the Kohl Grant application process. Egyptian artifacts and Buddhist statuary stood side-by-side there with Christian manuscripts, painted panels from Italian monasteries, and architectural fragments rescued from ruined churches all over Europe.

Although there was no explicit connection, astute visitors would begin to notice similarities, a number of shared motifs and symbols. Broken bodies, strange bodies, disfigured bodies. Monsters, the crippled, the dying.

Every year, Kohl Grant applicants were required to choose one piece from the museum for further study. Sarah’s essay, Dr. Kohl revealed, had focused on a piece that no other applicant had ever chosen before—but it was, he said, his favorite piece in the whole collection.

Sarah had not known this. No one had known this. She rewarded herself with a sip of wine.

Die Gesangbrüder, the surgeon continued, the “Singing Brothers,” had come from the ruins of an unusual church, destroyed by an errant British bomb in World War II, in a geographically stranded part of the German state of Hessen. The church should, by rights, have been in the neighboring state of Baden-Württemberg, but the meandering course of the river Neckar, a tributary of the Rhine, meant the church was in one state, the village it was meant to serve in another. It had been cut off, he said. Amputated.

Dr. Kohl had rescued the “Singing Brothers”—the only piece of the church his European dealers could locate for him—just before the rest of the building’s masonry had been ground to dust for new concrete or unrecognizably reused in other construction projects around town. For all he knew, the surgeon said, other pieces were still out there; perhaps Sarah’s research could help uncover them.

I would love that, Dr. Kohl emphasized. This was a request, she realized, a research direction she was being asked to pursue.

Relaxed now as much by wine as by her realization that her grant would not, in fact, be rescinded, Sarah asked the doctor a question. Her application essay had focused entirely on the craft of the “Singing Brothers”: the statue’s material fabrication, the tools it had most likely required, and the question of who had carved it. She realized now that she knew almost nothing about its original architectural context. Why hadn’t the church itself been rebuilt? she asked. That seemed unusual. Why had the townspeople not chosen to revive it?

That, Dr. Kohl replied, he also wanted to know. The church had lost its congregation long before the bombing, he said: it was a medieval relic, ruined by inattention before it was ruined by war. The townspeople had apparently avoided it for generations, he explained, telling dark stories about the place to their children as if to warn them away. Some people even said it wasn’t really Christian—that perhaps it hadn’t been a church at all.

Everything within, Dr. Kohl said, from the faces and forms carved into its arches, to its woodwork, murals, and paintings, had depicted twins. Conjoined twins, he added, although their bodies had been so heavily stylized that they could not have been medically accurate. Twins sometimes bursting forth from one another, entangled with each other, growing smaller versions of themselves, even consuming one another entirely.

The town, he said, had almost seemed happy to be rid of it.

OCTOBER 2022

The island’s police reached out to regional marine authorities with information about the boat, including its name and Cypriot origins, but the identity of the ship’s captain and crew, let alone its legal owner, had yet to be discovered. Whatever paperwork was on board had burned, and there were so few personal items stashed away, on so badly maintained a vessel, that it seemed clear the crew had gone to sea expecting little more than a few hours’ work.

Yet news of the ship had spread.

The doctor from a neighboring island came over the next morning, offering help, meeting the island’s own physician and its veterinarian on the docks. Mid-career, married, and doing well for herself, a mother of three, the doctor arrived expecting to perform a quick confirmation of some medical specifics: the crew’s deaths by fire or asphyxiation and, if she could determine it, their approximate date of death. Her job, she thought, was to supply the most basic timeline, to be an official signature on required forms, then head home.

But either the doctor had not yet been told the full story or she had severely downplayed what she’d heard, perhaps concluding that the description she’d been given was medically impossible, just panicked exaggerations from an island less sophisticated than her own.

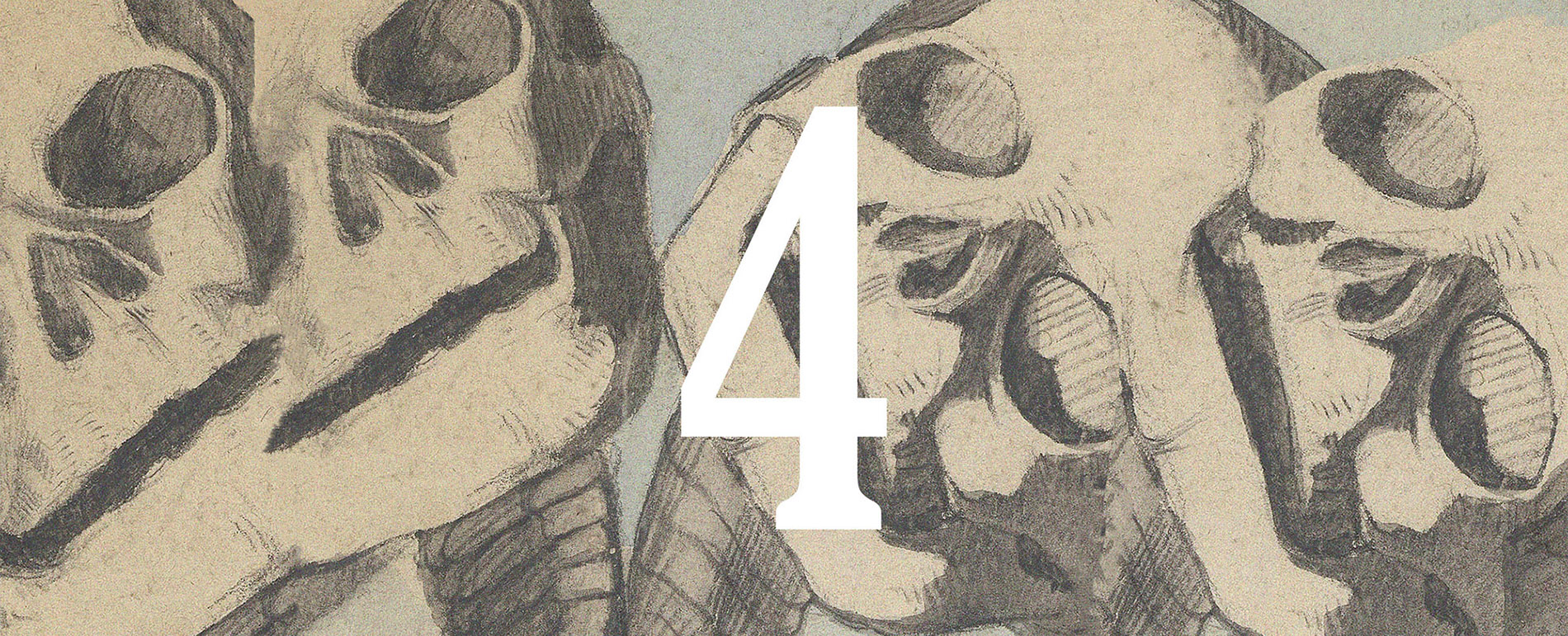

When the doctor stepped into the warehouse, across the threshold of the first refrigerated room, it was a moment marked by silence and horror. Before her, laid out across tarps on the floor, were scenes of anatomical incoherence. Blackened bodies with exposed bones seemed attached to one another at strange angles; single torsos carried three, even four, stunted legs; and faces on conjoined heads that should have been identical were, in fact, wrongly sized, more like shrunken versions of themselves frozen in expressions of pain they must have taken as flames consumed them at sea. It was a nest of bodies, stuttered by blurs and distortions.

The doctor stood there for so long, just staring, that a fisherman had to prod her.

Doctor? the man said. What is this?

The Canadian managed to catch a few hours of sleep, but nothing more. Before bed, he’d emailed several photos of the burned ship back to friends in Toronto, including a college acquaintance whose sister, he knew, now worked at the city paper. There was something strange going on, he wrote, though he didn’t have the full story yet. Nobody did. A shipwreck, a fire, dead bodies. He would get better pictures, he wrote, if he could.

Despite the early morning hour, he saw, the fishing warehouse was crowded. So many people were milling about outside, talking to each other in the street, that they seemed to have forgotten the presence of any outsiders on the island. The Canadian saw an opportunity. After a few minutes of waiting, he simply walked inside.

He need not have worried. Several islanders saw the tourist, glanced down at his camera, and just looked away, their eyes betraying a worry far larger than some foreigner taking photographs. The Canadian, testing this out, snapped a few shots of the warehouse interior, its stainless-steel work surfaces, its industrial fishing gear stored against the walls next to poles, hooks, and knives, its doors wide open out back, the burned ship perfectly framed in the harbor. He took a picture of that, too.

Near the doors, atop one of the tables usually reserved for prepping the day’s catch, stood a mess of objects offloaded from the boat. Tangled fragments of net, deck tools, someone’s half-burned duffel bag, and some fuel cans sat beside a collection of metal canisters—one of them broken open, as if it had burst—that the Canadian had seen the men looking at the night before. The canisters had been placed further away from the other objects, near the edge of the table; even as the Canadian was watching, two of the fishermen walked over and began inspecting them, looking for clues.

Voices from one of the walk-in refrigerators ahead caught his attention. Its door was pinned open by a folding chair and a small crowd had gathered outside, peering in. Above it all was a woman’s voice, speaking Greek with evident force and authority.

Flanked by fishermen in work aprons and gloves, the doctor, he saw, was squatting over the tarp, barking instructions. The men seemed to be holding onto several of the bodies, pulling them aside—pulling them apart—as if spreading their limbs to help her get a better look. Then the flash of a camera, again and again, and occasional groans from the villagers watching. Was this some sort of autopsy? The Canadian couldn’t get a good view. Through small gaps between people’s shoulders blocking the door, he could see the men grimacing, faces slack with revulsion, their aprons and clothes blood-flecked.

Then the shout.

It came from the dock outside. A young fisherman, no more than 18, was standing there beside the ruined boat. He was agitated, one hand wrapped in the other, turning away from everyone around him. He kept sneaking looks down at his hand and shouting, louder now, squeezing his arm ever closer to his body.

The doctor pushed her way out of the walk-in refrigerator, through the gathered townspeople, frustrated. What now? But perhaps she saw an opportunity. She could calm things down, demonstrate her expertise, focus everyone for just one moment on something medically straightforward—a simple work injury, she hoped, perhaps a cut, a puncture, a broken hand—anything that might distract from the horrible bodies entwined in the warehouse room behind her.

The young man was making a strange mewling sound now, like a scared animal, pushing his hand deeper against his belly as if to hide it. The doctor approached, calmly stopping him with a hand on his shoulder, an almost maternal gesture. Perhaps she was thinking of her own children, children she would soon see once this cursed day was over. She should never have come.

The doctor insisted now, reaching out, touching the young man’s forearm. Calm down. It’s okay. Be quiet.

But when the man finally revealed his hand, there was an uproar. Everyone backed away, some stumbling.

New fingers had emerged from the back of his hand, breaking away from the man’s knuckles. And they were moving.

Other men who had helped unload the blackened ship woke up complaining of stomachaches and chest pain the next morning and stayed home. For each of them, their fevers and chills were only getting worse.

In one house, a man began shouting for his wife: a painful ridge that had formed overnight on his breastbone, where he had been helping carry fishing nets off the damaged boat, holding them against his chest, had begun to swell. It was cracking outward, millimeter by millimeter, pushing his ribcage with it as if forcing open a jammed umbrella. When his wife came into the room and saw her shirtless husband writhing in agony, retching, trying to cough something up, she froze. The stubs of new ribs appeared to be growing from his chest like antlers.

In another house, a widower, living alone, never woke up at all. He would be found a day later, still in bed, the entire left side of his head stretched sideways, nearly double in size, one eye socket pulled open into a six-inch hole. His scalp had torn in places, revealing a fissure between the man’s skull and this malformed, bony sphere struggling to emerge from it.

All over town, for workers who had boarded the ship, such agonies were just beginning. Nearly a dozen men, their limbs cramping—somewhere on all of them, anywhere they had been exposed—their skin pushed from within by new growths of bone.

The doctor herself stepped backward, away from the young man, telling herself she just wanted to give him space. But this was a mistake: her reaction was interpreted as fear and the crowd responded accordingly. People began leaving—not fleeing, but turning away, quickly, instinctually, some gathering on the opposite side of the warehouse, but others heading straight home.

Let the doctor take care of this, they thought; let someone take care of this.

The Canadian was still by the back door, facing the docks, taking pictures, zooming in on what he could make of the man’s doubling hand. The confrontation he had once expected finally came. A woman, angry at the sight of this outsider with his expensive camera photographing the pain and embarrassment of a fellow villager, shouted something in Greek and pushed her hand against the camera lens.

Caught off-guard, the Canadian thrust his hand out to protect the camera, but—far more forcefully than he ever would have intended—knocked the woman’s arm away. From almost any angle, it looked as if he’d struck her.

Other townspeople rushed over in her defense. One man grabbed the Canadian’s camera strap and began to pull, the woman encouraging him, eager to get this pompous foreigner out of the way. The young dockworker with his terrible doubling hand was yelling ever louder in the background, the visiting doctor pleading with him in Greek. It was confusion and disarray on every side—when a tremendous back-to-back boom burst inside the warehouse. The man pulling on the camera strap fell over in surprise, hauling the Canadian down with him, the camera’s lens shattering onto the concrete.

Two of the pressurized canisters had blown, sending a cloud of mist over everyone nearby. Oily droplets rained down into people’s eyes, coating clothing and skin, forming a vaporous fog that sent anyone still on their feet rushing for open air.

The men who had been tinkering with the canisters now lay dead on the warehouse floor, their hands and faces mangled. The Canadian, sprawled beside his broken camera, mouth open in shock, realized he could taste something, that the oily substance had landed in his mouth and on his tongue.

JULY 1995

The man pulled up in his silver BMW and waved, carrying himself with a friendliness that gave away the many years he’d spent working in the United States. Married, with two young boys, the man had moved to Los Angeles as a West German and, by the time he’d returned, in 1991, it was to a reunited nation, a single country once again.

Sarah had been in southern Germany for nearly two months now, long by the standards of backpacking but no time at all in terms of serious research—and a mere blink of an eye for someone determined to learn everything she could about a region. Sarah had come as an art historian, of course, but, for her, art history had expanded into a different kind of investigation, something much larger than the statue she was supposed to be focused on.

The descriptions she had read of the church, written long before it was destroyed, taken from old journals, travelers’ pamphlets, and even a 19th-century novella, had given her an idea. Sarah had been developing a completely new approach to the “Singing Brothers.” She had not yet told Dr. Kohl or her grant coordinator about any of this, but she was increasingly convinced she was on the right track. While her colleagues back at home were doing internships for art museums or writing summer papers about Rembrandt and Van Gogh, Sarah was tracking down the truth behind a lost 15th-century church and its statues, where the truth appeared to be an undiagnosed medieval disease.

Before leaving Minneapolis, Sarah had put together a formidable list of research leads and contacts throughout southern Germany, mostly art historians, scholars, and dealers, people deep in the European humanities. She had done so with the assistance of Dr. Kohl and his artifact-procurement team, including a curator at the university’s archaeology museum and a private lawyer about whom she knew very little.

Her Kohl Grant, Sarah had quickly come to see, was not really an academic award at all—no wonder it paid so well, she laughed to herself—but more of a project fee for pursuing research of interest to Dr. Kohl. Whether this was genuinely intellectual or simply financial, Sarah did not yet know—after all, with every grad student Dr. Kohl sent abroad, he was adding to the breadth of knowledge associated with his own art collection, thus, in theory, contributing to its future value on the market.

The man picking her up that day was Florian Büchner—and, to Sarah’s thrill, she had discovered Florian’s research on her own. He was a geneticist by profession and an amateur historian by choice. His particular niche was tracking down apparently extinct medieval diseases. Florian was convinced that many of the descriptions of horrible deformities and monstrous creatures found in German folklore could, in fact, be explained by science: the bogeymen of yore might simply have been people afflicted with unusual diseases or genetic conditions that doctors, for whatever reason, no longer saw today.

It was one of Florian’s papers in particular that inspired Sarah to reach out: it described three cases, all from southern Germany, of what he believed to be a virtually unknown genetic abnormality. What caught Sarah’s eye was that the disorder was eerily similar to conjoined twins—with a terrible twist. Florian called it “post-natal twinning,” or bifurcation, by which he meant that the doubling process only began afterbirth. From what Florian could tell, based on medieval texts and engravings, the condition was inevitably, agonizingly fatal—yet, if those same descriptions were to be believed, it could begin as late as puberty. Imagine the horror of that, he would later say to Sarah. No one wants to become two.

When Sarah first spoke with Florian in his university office in the middle of June, he had never heard of the church. Nevertheless, he had responded to the premise of her research right. away. Sarah explained that she had been trying to build a larger historical context for Die Gesangbrüder and that she had gone down every rabbit hole she could find. The iconography of twins in European mythology. German folktales of twins, doubles, and siblings. Christian attitudes toward the deformed. Even, she said, clearing her throat, the twin-experiments of Nazi doctor Josef Mengele—who had been born, she added, here in southern Germany.

Yet none of her research had gone anywhere—mythology and iconography alone were not enough to make the art from her lost church make sense. Until, of course, she discovered Florian’s work on twinning.

The two of them had been sharing notes and research leads together for a month when Florian pulled up in his BMW. Sarah threw her bag in the backseat, hopped in, and they began the short but, they hoped, consequential drive up the river.

Florian had already lived up to his side of the collaboration; now it was Sarah’s turn. He had found, deep in the university’s medical archives, a manuscript from the 1400s. It described a generations-long outbreak of post-natal twinning in three small towns along the river Neckar. It must have been, he said, forty years of pure Hell: children from the age of six months to as old as fifteen would come down with fevers and cramps. Then a period of anguished waiting would begin. Within days, the children would begin to twin, helpless, terrified, other versions of themselves bulging outward through their spines and torsos, their skulls and ribs.

The timing of the outbreaks, Florian found, suggested that Sarah’s church had been built three or four generations after the disorder finally burned itself out, a memorial to the region’s trauma.

On their drive upriver that day, Sarah hoped that she could now fulfill her side of the collaboration. Only a few days earlier, she had come across new information that Dr. Kohl and his staff in Minneapolis had missed. Fragments of important historical sites, destroyed by war, had been preserved without ever being reconstructed. In local town records, she discovered several examples of architectural fragments being saved in storage facilities.

Most of the descriptions—all hand-written, some virtually indecipherable—were irrelevant to her research. One, however, grabbed her attention. It described the remains of a Klosterkirche, or monastery church, whose ruins Sarah had, in fact, already visited. Famously, this same monastery church had been partially reconstructed after the war, but was really just a stabilized ruin on the edge of the same town as the twin church, its vaults and arches deemed too complex, and too expensive, to rebuild. But, Sarah saw, its label had continued: the warehouse storing bits of the Klosterkirche had mistakenly included fragments of an “unknown chapel, 15th century,” alongside them—a church described as being on the river Neckar, just over the state line in Hessen.

Archives, Sarah thought, were like bodies. You never know what’s inside until it comes to light.

The two of them stood side by side, looking at the shelves in front of them, in a mix of revulsion and pride, horror and fascination. The warehouse they stood within, on the banks of the river, was alarmingly water-logged and very badly lit. A small house sparrow had flown in with them when the archivist first opened the front door; when the sparrow landed on a light fixture dangling from the ceiling above, it was as if everything in the room began to sway, shadows moving through shadows.

Stored amidst dust, mice, and roof leaks for the past half-century were at least a dozen carvings—mislabeled and thus unknown to the outside world—taken from Sarah’s ruined church.

The “Singing Brothers,” Florian joked, had many siblings.

Sarah tried to explain to the archivist who let them in, a woman in her mid-50s with her hair cut in a bob, why they were so interested in these stone figures, but her words came out jumbled, incoherent. She was still overwhelmed by what they’d found—by the fact that they had found it at all.

The archivist, however, seemed baffled. The three of them were, after all, looking at shelf after shelf of hideous human deformity, of faces melting into other faces, of bodies merged with other bodies, hideous and screaming, visibly in pain.

No matter, Sarah thought. She had become distracted, envisioning herself returning here, coming back to the warehouse with Florian the next day and the next, taking photographs and notes, even returning to Germany next year, perhaps turning this into her doctoral thesis, telling Dr. Kohl the good news, getting ahead of herself.

The archivist gave the sculptures one final, wary look before wandering off to a small front office, leaving Sarah and Florian alone with their talk of monstrosity. The sparrow eventually flew from its perch and the shadows on the sculptures grew still.

OCTOBER 2022

The Canadian was almost there. He could see the lights of the other village up ahead, just a few more hills and ridges to cross, maybe a mile away, but this headache—pain streaking down one side of his jaw in sharp bursts—was becoming intolerable. He should stop walking, he told himself; let the pain wash over, the agony fade. It would pass: of course, it would pass.

But he did not stop. He needed to get to the village—it was already dark, the stars out above him, the lights of ships visible in the maritime distance—and he needed their help. He needed painkillers. He needed a way off this island, now that the town he had been staying in had descended into chaos. A dozen fishermen grotesquely deformed, the visiting doctor complaining of chills, looking overwhelmed and terrified, anyone affected by the burst canisters complaining of pain.

The canisters, he thought. The oily liquid inside them—but he stopped himself. It had gotten all over him, in his mouth, on his face. Luckily, he told himself, pushing forward in the dark, it didn’t seem to be affecting him. Was it affecting him? No, he thought. No—he didn’t think so. But this headache, this pain he felt in his very bones. It was getting worse.

After the canisters had burst, his camera shattered, the Canadian had panicked. He fled back to his room at the inn. He had leapt into the shower, piled his soiled clothes on the floor, and sat alone on his bed, thinking about what to do next.

Shouts of agony and fear had been erupting all over the village. People coughing, hacking, calling out to each other in Greek. One man had fallen down in the middle of the street, screaming, the beginning of another torso now growing from his own; several other men in the warehouse had begun showing symptoms, bony protrusions appearing on their backs and shoulders, across their throats and chests.

The Canadian didn’t have access to a boat, he knew. Even if he did, he wouldn’t know how to use it. He didn’t have access to a car or even a motorbike.

Then he remembered the other village.

At the extreme northwestern edge of the island was another town. He knew there were paths that could take him there, long hiking trails that led up over the island’s central hills and gorges. He could just walk.

It would take hours, he knew, but if he left now—if he left right now—he could get there before dark. He could get away from this place. He could join a private boat to the mainland, he thought. He could find safety.

The village was right there, he saw, straight ahead, its lights a welcome glow in the darkness, beckoning him downhill. It had taken him longer than he thought, the sun now down for more than an hour. But he had done it. His eyes were blurring, this awful headache—it must be dehydration, he thought, he could barely see straight—this pain in his jaw really flaring, a stabbing sensation that seemed to radiate deep into his very teeth.

His teeth—the Canadian ran his tongue along the molars in back, over and over again. He didn’t want to think about what he felt there, that there were more teeth somehow breaking through his gums, the stumps of growing molars forcing his jaw to one side, his mouth swelling open.

Closer, he saw, closer: the village was just downhill. He would keep walking. He would find help.

The Canadian tried to calm himself by counting his teeth, using his tongue, one by one, tooth after tooth, but he kept losing count, getting confused, or—no. He stopped. There was something new. He could feel two tongues—one splitting from the other and expanding, forcing his jaw further to one side, pushing it wider, making it impossible to close.

He was jogging now, his jaw stretched painfully wide, swollen with the pressure of new teeth and a growing tongue, until, finally, he felt it break, his jaw dislocated.

Yelling in pain, the Canadian tried to cry for help. Please. He was all alone here, beneath the stars, becoming something he did not want to be. But the best he could do was emit a warbling sound, a wet animal howl as he stumbled downhill toward the village lights below—forty feet, he thought, thirty feet, he was so close—his nose now cleaving in half down the center line—twenty feet, ten feet—his face slathered with blood, but there it was, finally, he was walking toward the light, stumbling toward a village square, a small plaza.

He had made it.

The young girl, not quite 10 years old, bored of her family’s endless dinner, wandered away from the table outside. She hopped along the pavement cracks, from one stone to the next, but she was tired. She stopped in the middle of the village plaza and looked back at her family, hoping they’d be done, hoping the last bottle of wine would be empty, when a noise echoed down from the darkness of the hill behind her.

It was a gurgling of sorts, like an exotic bird, echoing down to the street. She looked at her family again but they were oblivious, roaring with laughter and drink.

The girl heard it again, more of a choking sound, like a growl. For the first time, she felt fear. It was crying now, whatever it was, a quiet whine—a creature in pain—getting closer, coming downhill in the dark.

Then footsteps, shuffling in the dirt just outside the plaza. Something coughed—or perhaps barked, she couldn’t tell—as it reached the edge of the concrete, a dark spot framed by buildings where no streetlights could reach.

Then it appeared: this tentacle-tongued thing, this man-like monster, its huge, doubled jaws dangling from a broken face, nose split asunder, its whole head bulbous, belly and chest covered in blood and drool.

The thing staggered toward her out of the darkness, eyes locked directly onto hers. To the girl’s horror, it didn’t look threatening. This was worse. It looked terrified, as if appealing to her for help.

Responding to her screams, the girl’s father and sister were first to arrive, running, followed closely by their neighbors. Her father leapt in front of her, protecting her, as the monster from the hill collapsed onto its knees. Its collar bones were beginning to duplicate now, breaking open like wings, revealing new and growing bones within.

The whole time, the creature’s eyes were moving back and forth, person to person, pleading, looking again at the little girl, desperate, tears running down its face.

The Canadian sat there like that, his throat blocked by another throat, gasping, choking on new parts of himself for minutes, endless minutes, before he could no longer breathe at all.

AUGUST 2001

Sarah stepped away from the plinth at the back of the gallery with a polite wave and a note of thanks—genuine thanks. It was a small crowd, no more than fifty, almost everyone there a close friend or fellow academic. But a crowd was a crowd, she knew, especially for a book about medieval German sculpture.

A small show of carvings from the German church—the Zwillingskapelle, as she called it in her book, the chapel of twins—was opening here at the university museum, where all of her research had begun, under Sarah’s curatorial guidance. Dr. Kohl had funded the shipment, installation, and insurance of the entire endeavor, with the understanding that two of the pieces would stay in Minneapolis permanently, joining the “Singing Brothers” in a renovated display.

The event that evening was part exhibition debut, part book signing. Sarah had finished her Ph.D.—it was Dr. Sarah, if you please, although she always found non-medical doctors using such titles to be pretentious—and turned it into a book less than two years later. No matter how many copies her book might sell, and she didn’t expect that would be many, Sarah was proud, justifiably so: she had done it. A weight off her chest, an entire phase of her intellectual life now enclosed by two covers. And, here in the last days of August, a quiet September looming ahead, it seemed like the beginning of a calm autumn to come.

The formal book-signing took another twenty minutes, after which the head curator congratulated her, offered her a glass of wine, and handed her a short note from Dr. Kohl. He could not make it in person, Sarah already knew, due to health issues, but he sent his congratulations—and pointed out in his note, to Sarah’s surprise, that the wine they were all now drinking was the same he had served at their initial dinner so many years before. Sarah took a nostalgic sip and looked around at the gallery, at the “Singing Brothers” and the statue’s newfound siblings. So many loops, Sarah thought, were finally closing.

Small talk, follow-up questions, photographs for the university magazine, and positive feedback all ensued. Soft music playing in the background. A clear summer night outside. Sarah loved it. Her fifteen minutes of fame.

In a moment of pause, a man approached. Sarah recognized his face from the book-signing earlier. He was intense and focused, almost clinical, but he did not have the air of an art historian, Sarah thought, even a person in the humanities.

The man introduced himself as a medical researcher, a geneticist from Nicosia. He had been living in the Twin Cities for the past year on a research fellowship—but nothing, the man quickly added, as interesting as her Kohl Grant.

He was astounded by her presentation, he said. He had never heard of any of this. He wanted to know if there was any chance this disease was still out there—if there might be signs of it, hidden reservoirs, maybe the occasional odd case flaring up, perhaps even in wild animals. He would love to study it, he said, to learn more about its long-term effects. The sculptures might have stopped in the 1400s, he suggested, but that didn’t mean the disease itself had gone away. It would be fascinating to see if it was still a threat.

Fascinating. Sarah laughed at this. How could anyone be excited to see such a horrible affliction in the world? But she caught herself. She had been asked similar things of her own research: why would such a nice midwestern girl like Sarah want to look at gruesome statues all day?

No, she started, there are no known reservoirs. But—and here, Sarah thought, why not? why not play with this, see where the idea goes?—if it is a genetic disorder, as Sarah wrote in her book, not a virus or a germ, then some local families might still carry the gene. You could do blood tests, she suggested, take samples. Look for the genes. Isolate the genes.

Sarah stopped herself—this was the wine talking, she knew. She was an art historian, not a medical expert.

But the man looked thrilled, nodding as she spoke. Yes, he said. Yes—that might work. Perhaps I’ll try that. Thank you.

Sarah later saw the man leaving, a signed copy of her book in his hand. Academia, she thought, finishing her wine, was full of such strange little people. Everyone pursuing their own isolated interests, never sure of what effects it will have on others along the way.

MARCH 2017

The two brothers saw no problem with their work. The Mediterranean was a huge sea. Anything their company might dump in all that water would eventually be dispersed, they told themselves; that was just common sense. Over the past year, the brothers had disposed of barrels, bags, and boxes, canisters, crates, and, once, a whole cargo container they had to saw holes into with an angle-grinder to make sure it would sink. And they did not lose sleep over any of it.

The company they worked for—part of a conglomerate owned by a hedge fund of some sort, they didn’t know and, frankly, didn’t care—had become masters of the global loophole, and the firm’s standards for disposal fell off more every year. Chemical waste, medical waste, toxic waste: they were licensed to accept all of it, expected to use the appropriate treatment facilities, places inspected by the full power of the European Union. But there was not enough profit being legal.

If anyone bothered to look at their paperwork that day, they would see that this particular load, allegedly destined for sanitary disposal, contained human tissue samples, vials of blood, chemical reagents, the bodies of horribly deformed laboratory mice, and a collection of roughly two dozen pressurized canisters. A professor at the university up in Nicosia had died—a geneticist who, at one point, worked in Minneapolis for a year and had spent half a decade studying recessive genes in southern Germany—and this was the result of a cull. The school had saved what they thought they needed from his lab and made a decision to eliminate the rest.

University administrators had done it the right way, they thought, consulting with a fellow professor—who, they did not know, wanted nothing more than to see her colleague’s controversial work come to an end. He had been doing terrible things—breeding conjoined mice, doubled limb by limb, all dying in pain—and pursuing gain-of-function research on the human genome without any appropriate safeguards. Several times, she would come into the shared lab space the morning after another of his late-night sessions and find strange websites still in the browser history. Political sites. Conspiracy sites.

The man’s heart attack had been a blessing, she thought. This was not research anyone should be doing, and, if regulators ever found out, she worried, it would tarnish the entire university. She thus ordered a purge: the dead professor’s experiments were discontinued, his biological and genetic samples marked for autoclave sterilization.

The school, once again, did everything right, or so they thought: they contracted with a licensed disposal firm—but, truth be told, it never occurred to them that the waste might not be going where the invoice said it was.

Someone just came and picked it up, and then it was gone.

The two brothers aboard the waste ship that day went through their usual routine; it had worked before and it would work again. They spoofed their GPS transponder, scanning both the radio and the horizon for nearby inspectors. Satisfied, they began dumping their cargo.

Somewhere amidst this great plug of rubbish and waste destined for the Mediterranean seabed were two dozen canisters from the researcher’s lab. The canisters drifted down through the currents, jostling against each other like bells ringing in the deep. They. might stay there, buried by silts and muds, for thousands of years, or they might be punctured by curious sea life—or, who knew, they might get pulled up someday by some unlucky crew’s fishing net.

It wasn’t the brothers’ business to care. They checked their hold, saw it was empty, and began the long journey back to shore.