This Pakistani Filmmaker Wants to Break the Silence on South Asia’s Rape Problem

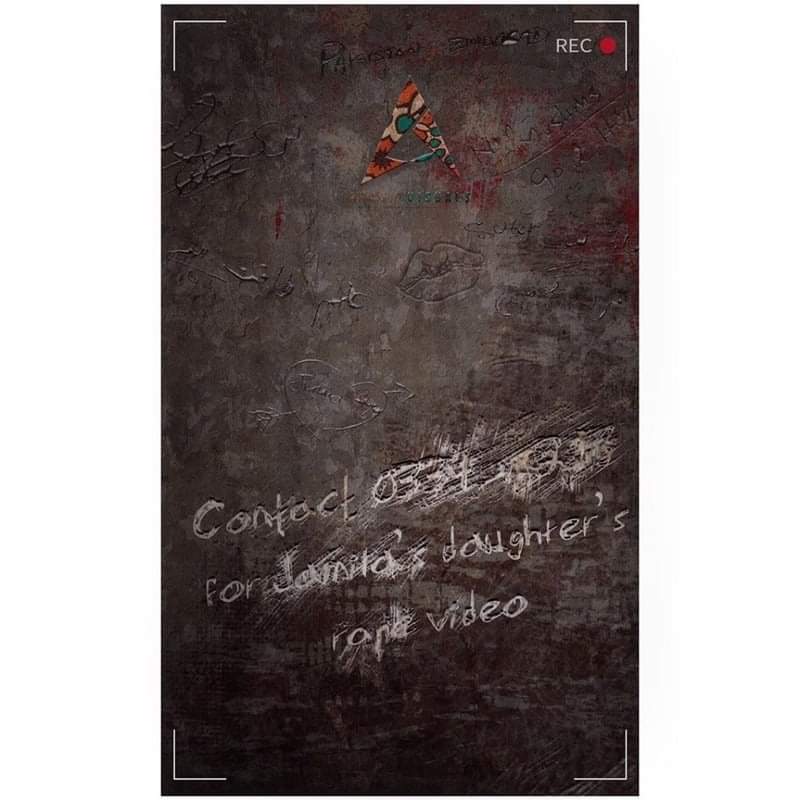

October 29, 2020The first few seconds in the nine-minute Pakistani-American short film, “Blue: A Kaleidoscope”, is a faceless conversation between two women in an undisclosed location in Pakistan. They’re discussing the return of a girl called Jameela in their neighbourhood. “Wasn’t she kidnapped?” one of them asks. “Yes, she was but they threw her back,” the second woman says. “I heard she was raped. They made a video of her as well and it’s all over the internet now.”

“What a shame,” the first woman said, adding that this is what happens when parents let their daughters play outside wherever they want. “She’s disgraced the whole neighbourhood.”

Pakistani filmmaker Danial K Afzal, 29, who directed “Blue”, knows the implication of this casual exchange. In a society such as Pakistan, or in any part of South Asia, patriarchal mindsets have been institutionalised, and deny agency and justice to women who are subjected to all forms of atrocities.

Last month, two rape cases—in one, the victim was a minor—triggered nationwide protests in Pakistan.

The cases keep rising, nevertheless. Early this month, a report by Islamabad-based NGO Sustainable Social Development Organization found a spike of 400 percent of child sexual abuse and rapes during the country’s lockdown. In an interview last month, Pakistani Federal Minister Fawad Chaudhry said that an average of 5,000 rapes are registered every year. Only 5 percent lead to convictions.

Afzal looked into real-life incidents around him to create the fictional short film on the struggles of a rape survivor. In 2016, his first documentary feature “The Survivor” looked at the post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) of a survivor of a high school massacre in Peshawar in 2014, which killed at least 150 people, mostly children.

VICE News caught up with the filmmaker, who opened up about venturing into “dangerous” subjects, understanding trauma from personal experience, and more. Excerpts:

VICE News: How did this movie come together?

Danial K Afzal: When I made my first film, ‘The Survivor’, based on this kid who survived the Peshawar school attack in 2014, we looked into the PTSD of the child. And then, last year, the Zainab Ansari rape and murder case happened. That triggered us and pushed us into working on ‘Blue’. It was also interesting that sexual assault, especially towards adoslescents and young kids, is quite rampant in my part of the pond, but nobody talks about it. Everybody shoves it under the rug. This film is dedicated to women who have been judged and hushed for being the victims of sexual assault and rape.

Why is there a reluctance to talk about sexual assault, especially on children?

This is true especially of men in South Asia, who still do not understand the prevalence and intensity of the problem. Yes, we do come out and show our support. But if we look into the root of the problem, all men, including me, were taught to look down on women in some way or the other. We still need to learn a lot.

Where did your interest in PTSD stem from?

PTSD is rampant in Pakistan and India. In Pakistan, especially, it’s a controversial issue. If I have to see a psychiatrist and psychologist, it becomes an issue. That stigma is there. But any kind of abuse has PTSD attached to it—be it emotional, physical or sexual. We’re not talking about this, and that concerns me.

In both ‘The Survivor’ and ‘Blue’, you looked at the problem from a child’s perspective. Why?

When I was growing up, I was emotionally abused. I will turn 30 in 11 days, but over the years, I’ve seen emotional bruises from as early as seven years of age. They’re still attached to me. Trauma, they say, is carried from generation to generation. This is why I focus on kids.

Did you face any criticism when “Blue” came out?

Recently, The Independent covered Blue and they put it on their social media. Some Pakistanis commented asking why I’m showing this negative picture from the country? One man said that people would be more determined to pursue rape after watching my film. I was flummoxed. To me, I’m highlighting closeted issues that nobody dares talk about. I want to bring the monsters out through my work.

I also got messages by women who said, ‘Thank you so much for making this.’ We got messages from survivors, which I can’t talk about. The film came out around the motorway incident also, so we got a huge response and news coverage.

Do you think films can be an effective way to start a conversation around such subjects?

I feel that this conversation is still limited to urban spaces in Pakistan, where people sit with support groups and friends. But can I have this in a rural setting? No. Every year, the Aurat March is a huge controversy. All women are doing is coming out and demanding their rights. But these women can’t march in small, rural pockets where, forget about marching, they can’t even come out of their homes.

Recently, a woman journalist was in a marketplace in Rawalpindi, interviewing people after the motorway case, asking if women have freedom in this country. Rawalpindi is a very urban city. But a man responded, on camera, that if women like her come on air, these things will happen.

So, people like you and I will talk about such topics. The challenge is to reach out to people who do not want to listen. I want to do that with my work.

Follow Pallavi Pundir on Twitter.