Can South Korea’s Club Culture Recover From COVID-19?

August 24, 2020These days, the once vibrant Seoul neighborhood of Itaewon feels stuck in time. As the rest of the city—and wider South Korea—slowly attempts to regain a sense of normality amid a global pandemic, this neighborhood continues to struggle with the stigma of the coronavirus. In May, Itaewon was singled out as the source of a new cluster of COVID-19 infections. Since then, the crowds stayed away from Itaewon.

Now, many of the neighborhood’s business owners wonder whether this stigma will be harder to beat than the pandemic itself. “I think people have just been avoiding Itaewon for longer than they needed to,” explained Mipa Lee, the owner of Plant Cafe & Kitchen, a vegan restaurant that opened in Itaewon seven years ago.

During the second quarter of 2020, vacancy rates for large and medium businesses in Itaewon rose at a rate about four times faster than the rest of the city, totaling a 29.6 percent rise in empty commercial buildings by the end of June according to the Korea Appraisal Board. The neighborhood maligned in the press as the source of more than 100 new infections definitely helped accelerate the increase in vacancies, but for many who lived and worked in Itaewon, COVID-19 added fuel to an already burning fire.

Once seen as a gritty international neighborhood in the shadow of a large U.S. military base, Itaewon began to slowly gentrify more than a decade ago as businesses moved in to take advantage of its low rents.

By the time Lee opened Plant Cafe & Kitchen, Itaewon was already in the midst of a transformation. “The first couple years of operating was, for me, the prime of Itaewon where it was always busy,” she told VICE News. “Every weekend there was something going on.”

But rents continued to rise and older businesses began to leave the neighborhood. By 2015, rents spiked and remained high, creating an all too common cycle of boom and bust that left Itaewon struggling with vacancy rates more than double the national average by 2019, according to data.

The U.S. military base, a source of both tension and prosperity for the neighborhood for decades, also decided to pull out of Seoul entirely, moving thousands of U.S. personnel and their families 37 miles south to the city of Pyeongtaek, casting further doubt on Itaewon’s future.”With the U.S. Military base right here—and the soldiers—they brought a certain energy with them, and then when they were slowly transitioning to move to Pyeongtaek, that energy just slowly left with them,” Lee said.

Soon, an area that once catered to Seoul’s international families during the day and its party crowd at night shifted back to one where the streets were most crowded after dark. And then, as Itaewon’s clubs became a cautionary tale for nightlife reopening during the pandemic worldwide, those afterdark crowds vanished as well.

Globally, the pandemic is exposing cracks in societies and systems, and in neighborhoods overly dependent on bars and nightlife to survive, COVID-19 has turned these cracks into chasms. In Seoul, Itaewon’s night clubs don’t stand alone, they’re part of a wider ecosystem of businesses that is now breaking apart.

“If there are no clubs, there’s nowhere to go after drinking, so the bars have less patrons. If bars disappear, the restaurants will be affected too,” said Moon Jung-tack, a DJ and the owner of Club Volnost. “People don’t come all the way to Itaewon just to eat and then go home. It’s going to become a vicious cycle.”

Seoul isn’t alone in struggling to figure out how to reopen nightlife in the middle of a pandemic. Bars and clubs were the source of similar COVID-19 outbreaks in Tokyo, Florida, and Berlin to name just a few.

But in South Korea, clubs were already stigmatized before the pandemic hit, especially in the aftermath of a horrific scandal involving rape, sex traffickng, corruption, and drugs centered on a club partially owned by some of the biggest names in K-pop.

That club, Burning Sun, was in a totally different part of Seoul—Gangnam—and was worlds apart from the scrappy underground clubs in Itaewon like Faust, Concrete, and Volnost, but the scandal painted all of Korea’s clubs in a negative light.

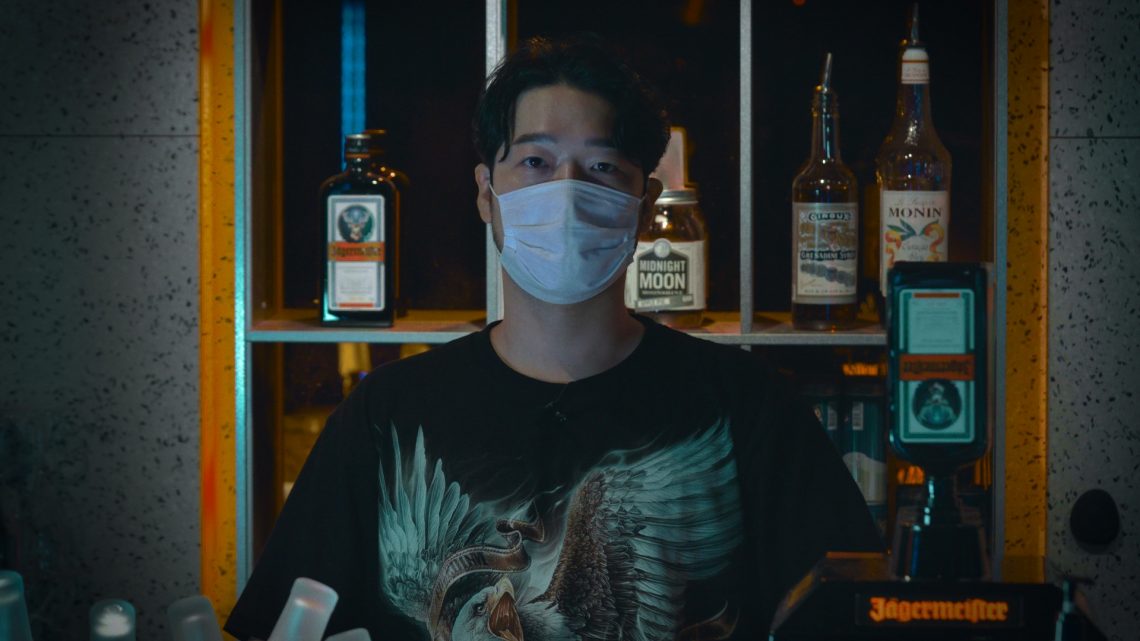

Then, because Itaewon’s COVID-19 cluster originated in a handful of clubs in the neighborhood’s LGBTQ nightlife section, Korea’s media added a homophobic layer to the stigma as well. “There’s a tendency to view clubs and club culture negatively in Korea, so there’s no support and we can’t just sit around waiting,” Moon said. “A lot of clubs are unable to stay afloat and are closing down.”

Club owners say the law doesn’t explicitly close nightclubs during the pandemic, but makes it impossible for them to operate – allowing the government to skip out on providing any sort of COVID-related support. “If the government issued an administrative order to shut down our businesses, they would have a responsibility to provide a monetary solution, but the phrase they’re using is ‘banning large gatherings’,” explained Lee Myung-ha, the owner of Faust.

“It’s a play on words,” he continued. “They get off on a technicality without providing us with a means to survive.”

It raises some difficult questions, like can Itaewon succeed and rebuild without the bars and clubs that helped drive its growth? “Part of what has made Itaewon a popular place for nightlife is the diversity of places that people can go,” said Richard Price, co-founder of Seoul Community Radio. “For that to not be protected, it's quite a disservice, actually, because it's the foundation of what the area really is about.”

But there might be a solution. The pandemic also fuelled the growth of the Korea Club Culture Betterment Association (KCCBA), a collective of the small business owners whose establishments are a part of Seoul’s rich underground club culture. The KCCBA is now trying to get the city government to pay more attention to their needs.

“We say this as the association a lot, but are they leaving us out to die?” said Lee, of Faust. “Does Korea want to get rid of all the clubs? Do they really find no value in this culture? Or is it because we don’t have a voice yet to reach the government?”

For others, reinvention and self-reliance is a part of what made Itaewon such a resilient place all these years. “I feel like Itaewon has this grit to it and it’s got this scrappy nature that it’ll figure it out,” said Lee, the owner of Plant. “Like, I’m not hoping or even optimistic that it will go back to what it used to be, I think that Itaewon is kind of in the past now and we just have to kind of create something new now.”