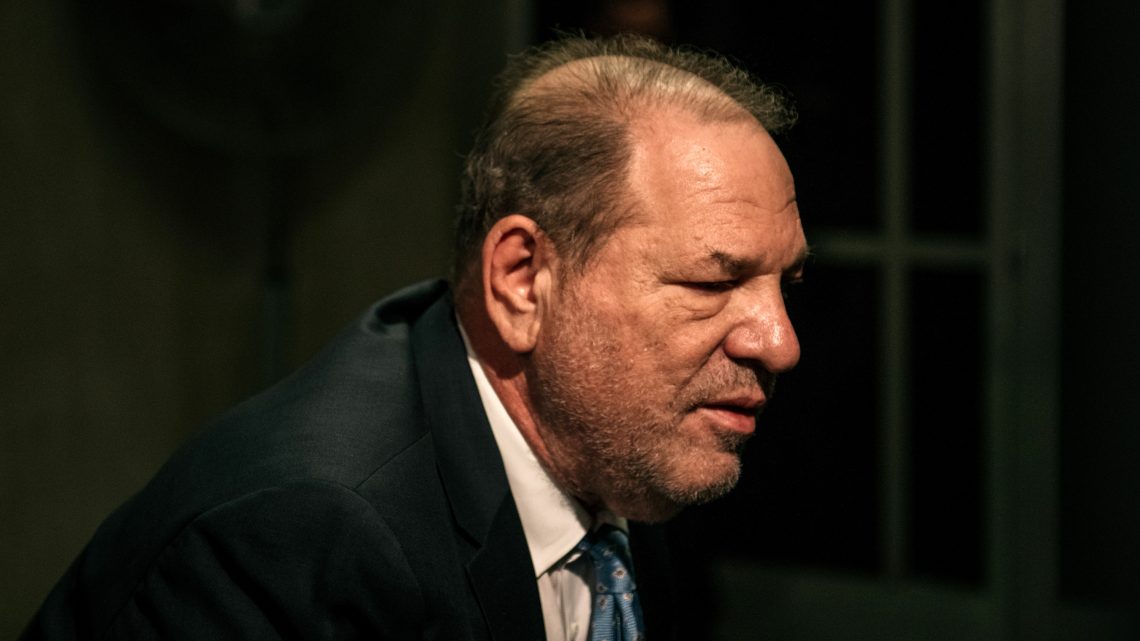

Weinstein’s Guilty Verdict Is a Victory for ‘Imperfect’ Victims

February 24, 2020After six weeks of trial and four days of deliberation, a jury on Monday found Harvey Weinstein guilty of sexually assaulting a woman and raping another. While most news coverage so far has highlighted that Weinstein was acquitted of the most serious charges, the third-degree rape charge is a milestone decision for sexual assault survivors who don’t fit the suffocating mold of the perfect victim.

In New York, third-degree rape applies to anyone who either can’t (through intoxication, or physical or intellectual disability) or didn’t give consent; it’s a distinctly different charge from first-degree rape, which involves very young minors and/or “forcible compulsion,” usually involving a weapon. According to her testimony, she wasn’t intoxicated or otherwise disabled, meaning the jury understood and agreed that she didn’t willfully give consent, despite other instances of consensual sex, a rarity in sexual assault trials.

Weinstein faced five potential charges in New York, and received guilty verdicts for two of them: criminal sexual assault in the first degree for forcibly performing oral sex on Miriam Haley, and rape in the third degree for allegations from Jessica Mann, whose credibility was repeatedly attacked throughout her three-day testimony. The charges he was not convicted of included two counts of predatory sexual assault, which could’ve landed him in prison for life, and a charge of rape in the first degree.

Even though we know, from lived experience and from psychiatric literature, that there’s no one way that survivors of assault behave, a criminal law expert in Brooklyn told VICE that it’s rare to get any degree of rape conviction in cases where the survivor doesn’t behave like we expect survivors to behave. And Mann didn’t. The defense focused on Mann’s on-and-off five year relationship with Weinstein, one in which she often thanked him for things like invitations to Hollywood parties, solving a parking ticket, and helping her get a job as a celebrity hairstylist. Weinstein’s defense team drew particular attention to an email she sent him in April 2013, one month after he raped her: “I appreciate all you do for me.”

Weinstein’s attorneys used all of this as evidence to support an unoriginal argument that a survivor of assault would never act kindly to her attacker. The result was a particularly brutal, three-day testimony, in which Mann openly sobbed on the stand, and could, at one point, reportedly be heard screaming from a back room.

Many survivors probably recognize their own behavior in Mann’s. It’s not uncommon for people who’ve been raped to continue having consensual sex with their attackers. “This looks like weakness, but it’s an attempt to gain control,” journalist Jia Tolentino wrote in an October 2017 story in the New Yorker on Weinstein’s accusers. The reasons why someone might return to an attacker are deeply personal and singular, and don’t necessarily need scientific and legal prodding, but belief.

In a news conference on Monday, Manhattan District Attorney Cyrus Vance said these verdicts mark a “new landscape for survivors of sexual assault in America.”

This New York jury’s belief in Mann, a realistically imperfect victim, is not only a remarkable sign that the momentum of the Me Too movement is causing necessary reform, but one that signifies hope for all equally complex survivors going forward.

Sign up for our newsletter to get the best of VICE delivered to your inbox daily.

Follow Hannah Smothers on Twitter.