Harvard Professor Lawrence Lessig Sues New York Times for Describing What He Said

January 13, 2020Harvard law professor, free-culture proponent, and former presidential candidate Lawrence Lessig announced today that he is suing the New York Times for summarizing his opinions on whether and how institutions should take money from accused child rapist Jeffrey Epstein and other criminals in a September article titled “A Harvard Professor Doubles Down: If You Take Epstein’s Money, Do It in Secret. ”

On a new website devoted to the lawsuit, Lessig coined what may well hold as the most embarrassing phrase of the year: “Clickbait Defamation.” At Lessig’s newly launched clickbaitdefamation.org, one can find not only an essay about the lawsuit, but also a podcast about the lawsuit, a fully produced five-and-a-half minute video about the lawsuit (which I urge you to watch in full), and a fundraiser to get people to cover the legal fees stemming from the lawsuit. What you won’t find is a clear basis for the lawsuit.

In a 44-page complaint filed in Massachusetts District Court in Boston, Lessig, who told VICE in an email that he is represented by Howard Cooper of Todd Weld, claims the “clickbait” article has harmed his reputation and asks for a jury trial. The lawsuit says that the defendants—Lessig’s not just suing the New York Times but also reporter Nellie Bowles, business editor Ellen Pollack and executive editor Dean Baquet (identified as Daniel Paquet in the filing)—“published their headline and lede despite their both being the exact opposite of what Lessig had written and despite being told expressly by Lessig pre-publication that they were contrary to what he had written.”

The Times article, published September 13 , included an interview with Lessig based off a 3,500 word Medium essay he wrote in defense of his friend Joi Ito, the now-former head of the MIT Media Lab, who resigned after it was revealed that he not only twice visited Epstein’s Caribbean island (allegedly a hotspot where Epstein and his pals had sex with trafficked underage girls), but solicited and accepted donations from Epstein, then worked to cover it up. In the essay, Lessig wrote that in a perfect world no one would take money or funding from criminals and pedophiles, but that in practice, many universities and institutions do take money from shady and immoral sources. The critical part of Lessig’s Medium post came after he classified four types of donations—money types 1, 2, 3, and 4, in his taxonomy. Epstein’s donation, Lessig wrote, falls under type 3: “People who are criminals, but whose wealth does not derive from their crime.” Here, Lessig assumed for the sake of a hypothetical that Epstein amassed his wealth through legal avenues and then wrote, “IF you are going to take type 3 money, then you should only take it anonymously.” In an addendum he tacked on to the essay after it had garnered attention, Lessig wrote, “it was a mistake to take this money, even if anonymous.”

Do you work at the New York Times, or with Lawrence Lessig? Contact the writer at laura.wagner@vice.com or laura.wags@protonmail.com.

Elsewhere in the Medium essay, Lessig made his original point repeatedly and clearly. “I think that universities should not be the launderers of reputation,” he wrote. “I think that they should not accept blood money. Or more precisely, I believe that if they are going to accept blood money (type 4) or the money from people convicted of a crime (type 3), they should only ever accept that money anonymously.”

Not only is this almost identical in meaning to the New York Times headline—”If You Take Epstein’s Money, Do It in Secret”—but Lessig emphatically restated this exact belief in his interview with the Times. “If you’re going to take the money,” he told Bowles, “you damn well better make it anonymous.”

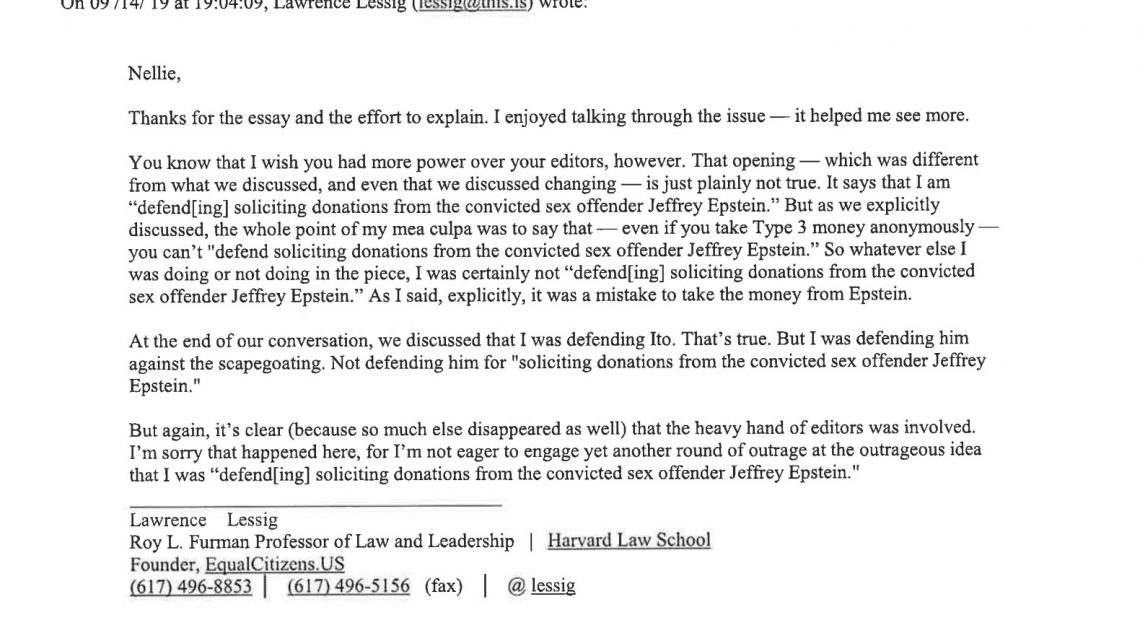

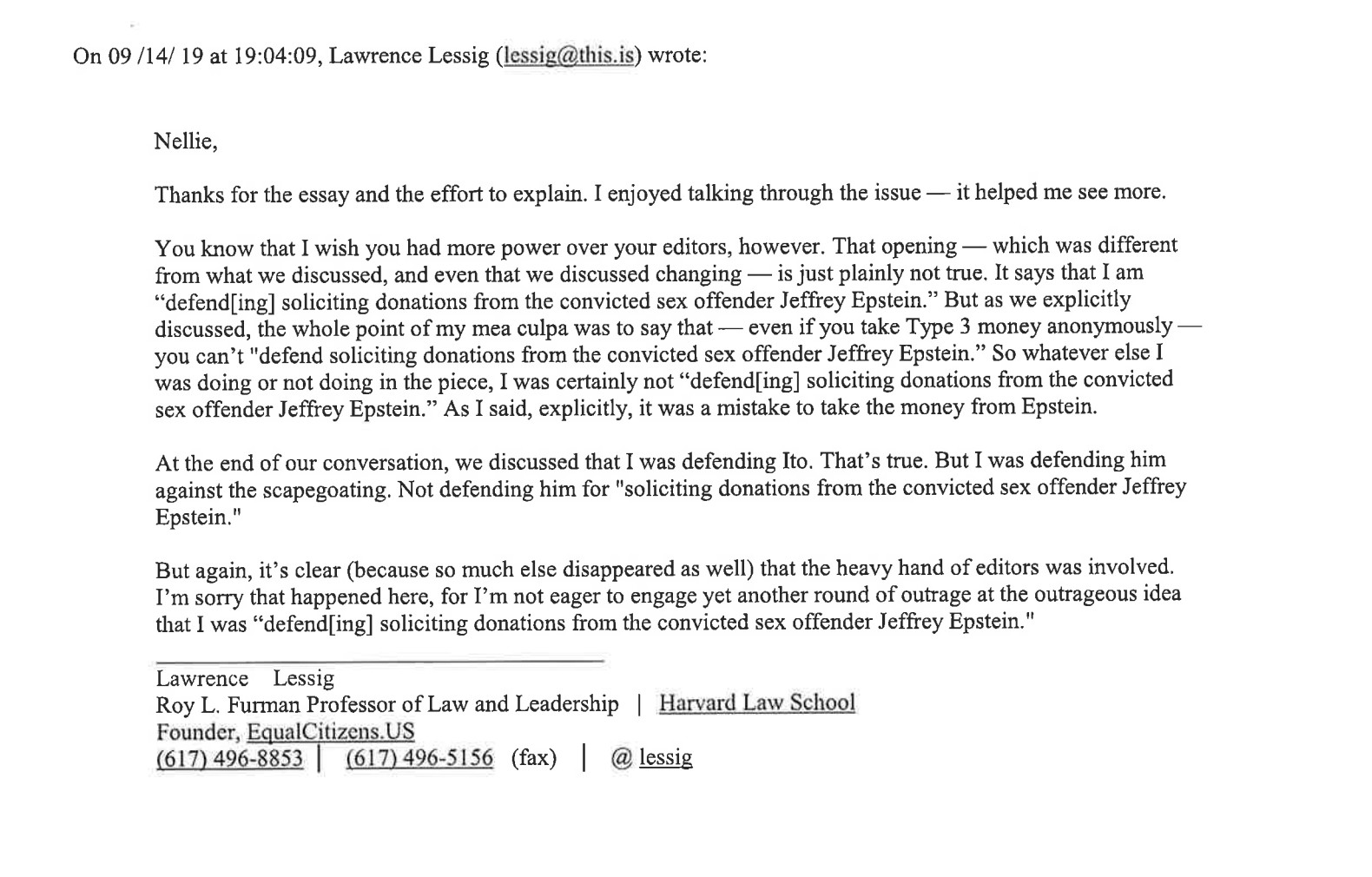

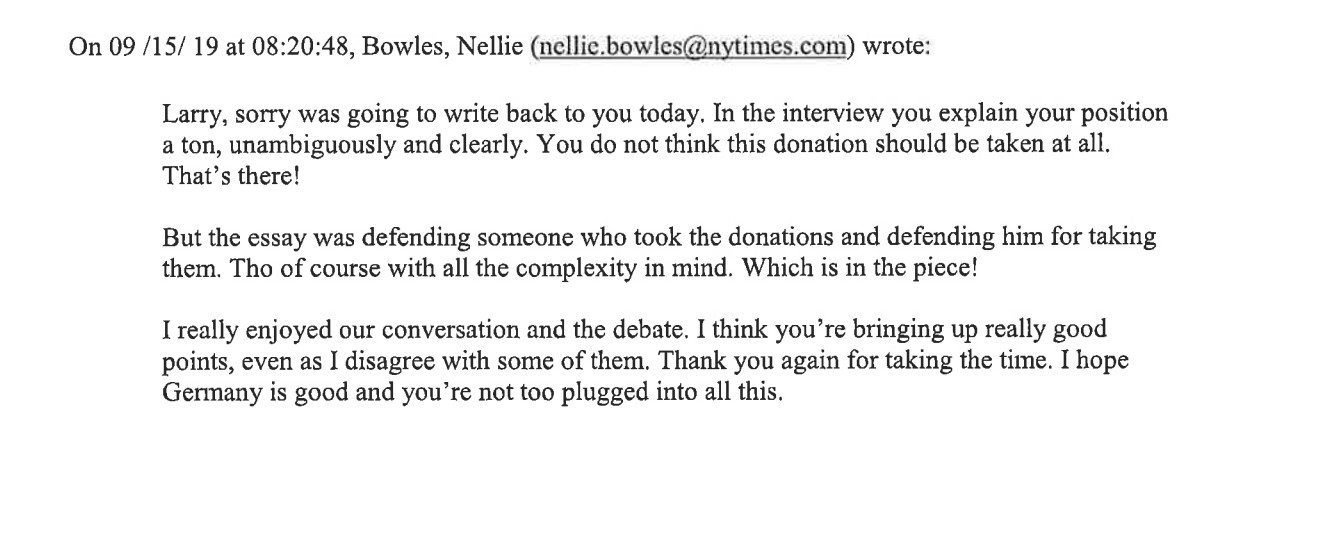

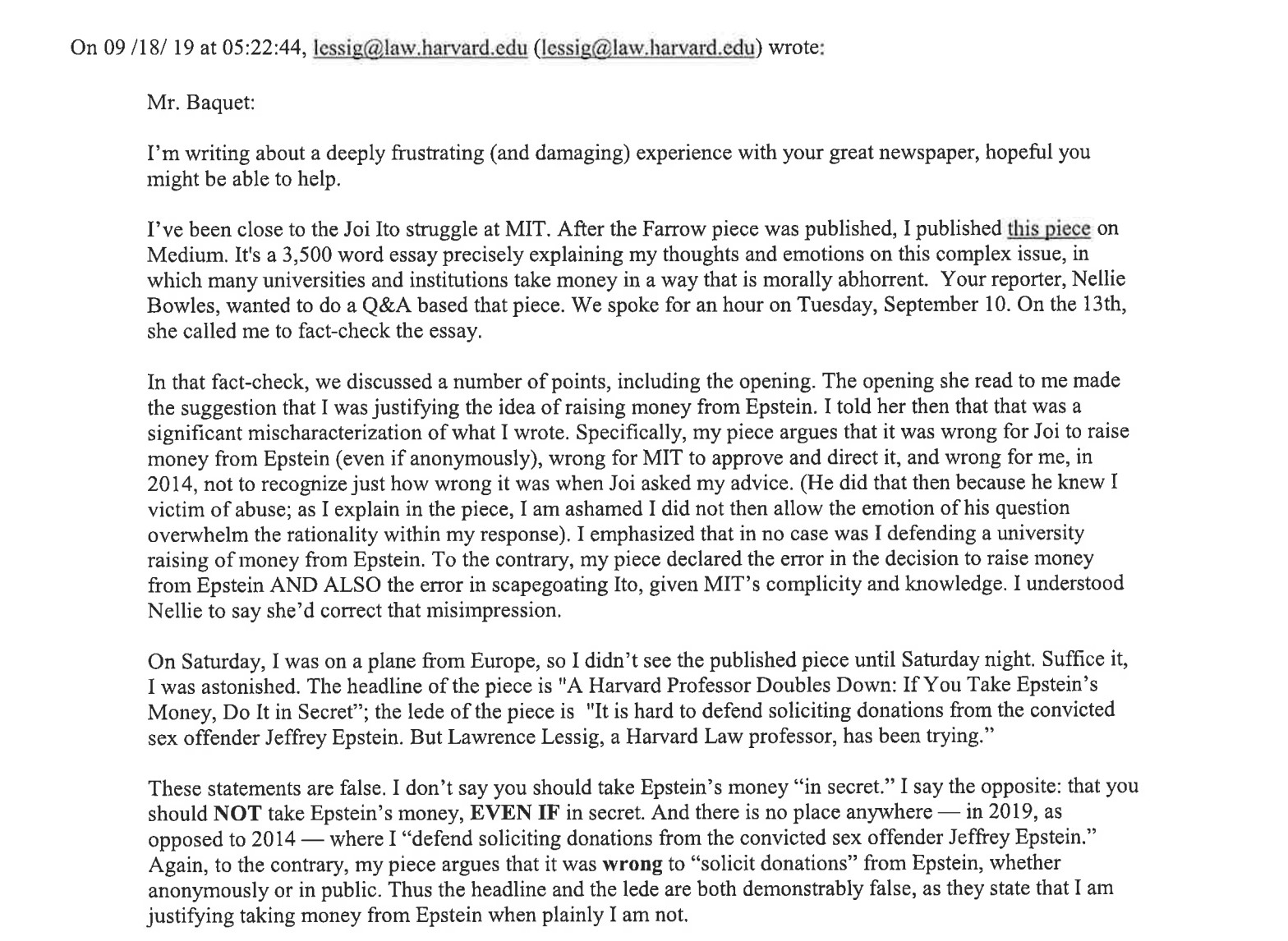

The crux of Lessig’s defamation lawsuit argument is difficult to parse. His exchanges with various people at the Times, which are included in the lawsuit, do not bring much clarity. Here’s the exchange with Nellie Bowles:

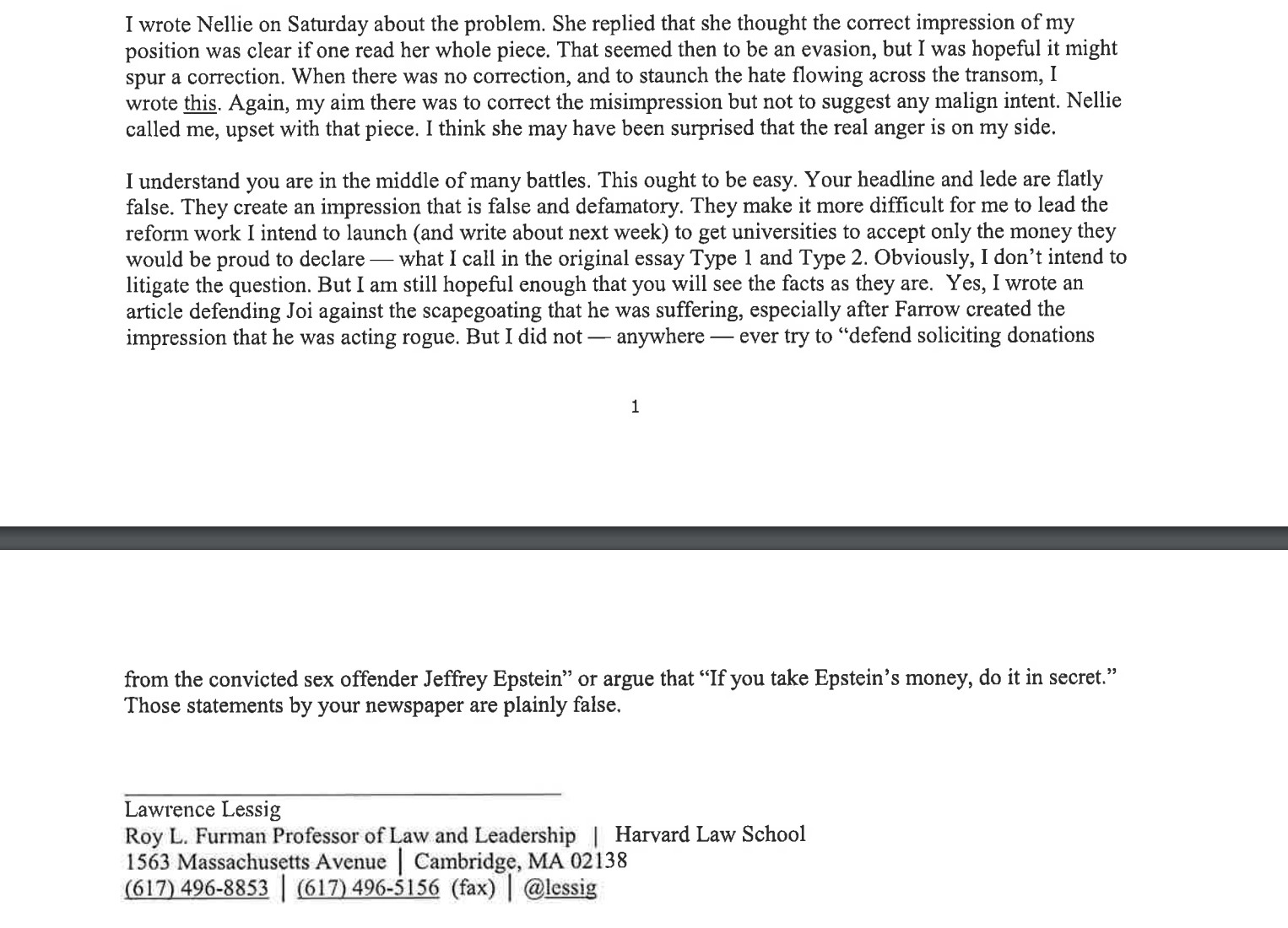

This is what Lessig wrote to Baquet:

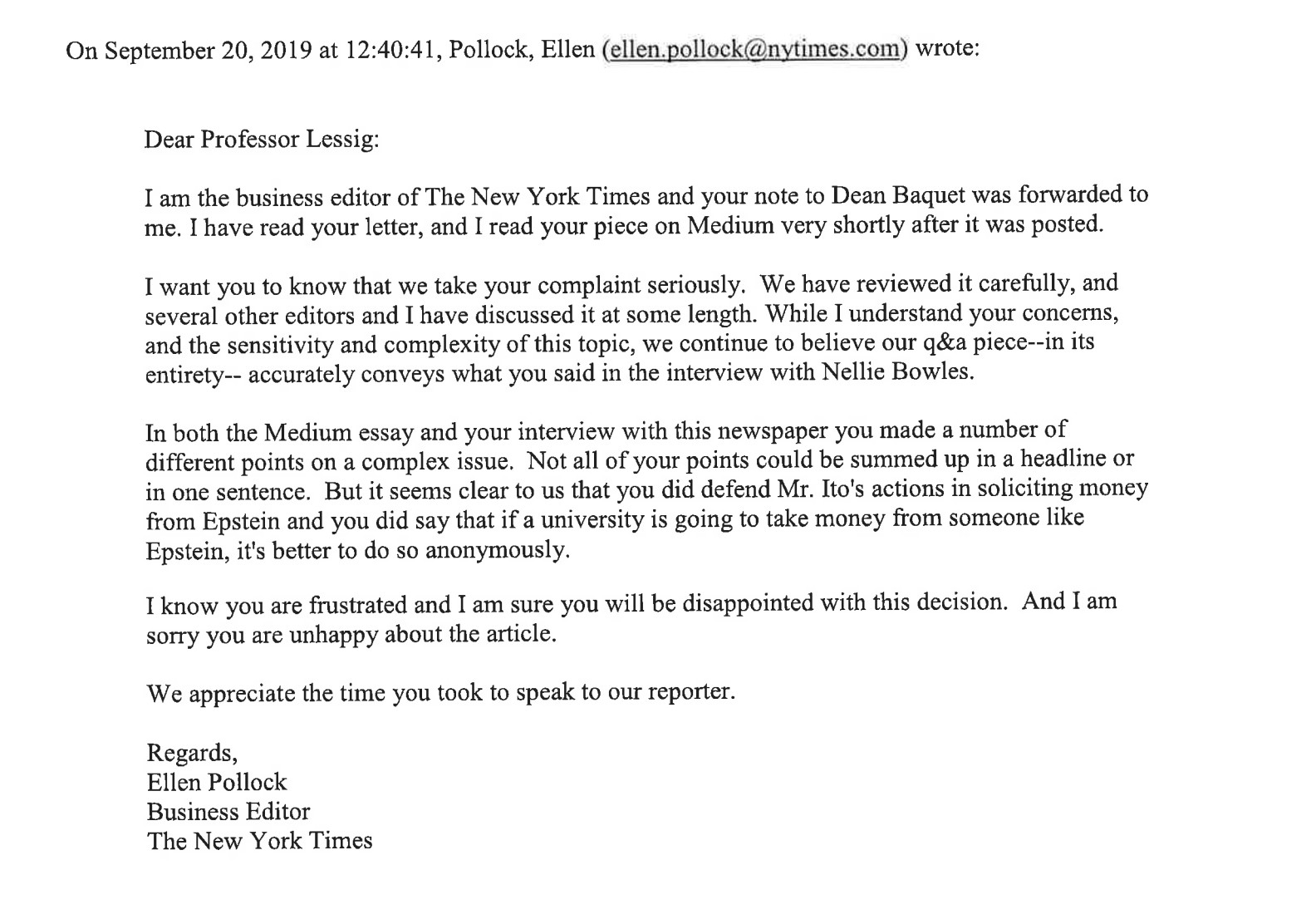

Notably, Lessig wrote, “Obviously, I don't intend to litigate the question." (When asked today what changed his mind, he answered VICE thusly: “Their reply! And the ongoing burden I experience of people either calling me out in person or on social media based on the false impression created by the story.”) Baquet forwarded the email to Pollock, who responded:

Lessig told VICE that the burden wrought by the article “has been persistent and pervasive.” He produced this tweet from Sunday, which has one retweet and one like, as a recent example. Lessig, however, isn’t just suing simply because he thinks he was defamed by the New York Times. The lawsuit takes a grander view. Lessig sees himself as fighting against clickbait’s corrosive effect on journalism.

On his website, Lessig writes:

Unchecked, clickbait corrupts journalism. I have brought this case to challenge that corruption. The incentives to use clickbait are real. The return from clickbait is substantial. So long as the headlines and ledes are true, there is no harm. When they are false — and when, upon notice, that falsity is not corrected — there should be consequences enough to create the incentive to do better the next time.

The term “clickbait,” itself a tautology, has long been understood to mean “anything someone doesn’t like” and is deployed in largely the same vein as “fake news.” Lessig’s lawsuit is arguing for a precedent that would allow people to sue journalists if they don’t like the framing of a story.

VICE asked Lessig for some other examples of clickbait journalism; he declined to provide any, citing an unwillingness to “get in the middle of things.”

In a statement to VICE, a spokeswoman for the New York Times said:

"When Professor Lessig contacted The Times to complain about the story, senior editors reviewed his complaint and were satisfied that the story accurately reflected his statements. We plan to defend against the claim vigorously."