The Southern Poverty Law Center Is Unionizing After a Year of Scandals

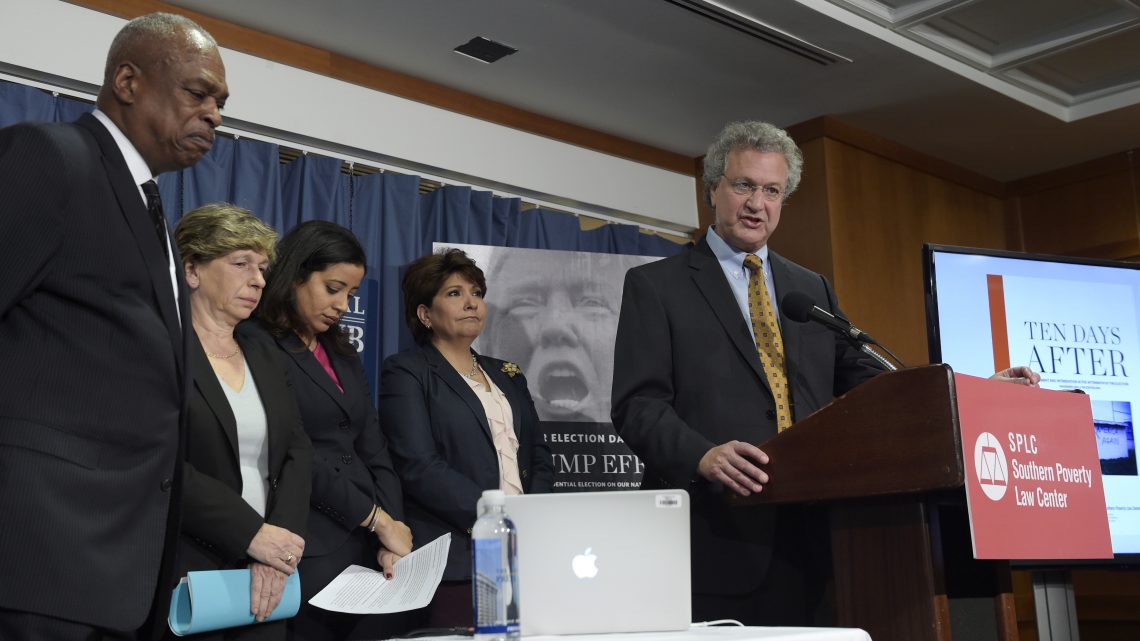

November 8, 2019On Thursday, workers at the Southern Poverty Law Center announced that they had formed a union. "Our mission," the union's organizing committee told VICE in an email, "is disrupting white supremacy, pursuing equity, building solidarity and uniting workers at SPLC." The announcement comes after a tumultuous year for the nonprofit, in which both the co-founder and the president were forced out amid allegations of misconduct.

Founded in 1971 and based in Montgomery, Alabama, the SPLC has grown into one of the oldest and most influential liberal institutions in the country, bringing a number of landmark civil rights cases and pursuing deep investigative work into white supremacy and the far right. It's perhaps best known for its famous list of "hate groups," which has drawn controversy and lawsuits from right-wing organizations like the Center for Immigration Studies and the Proud Boys, which objected to their inclusion on the list. The nonprofit has also been subject to criticism from the left over the years, not only for its fundraising practices but for the limits of its political vision. The SPLC Union, which is organizing with the Washington-Baltimore News Guild, a local of the Communications Workers of America, is seeking voluntary recognition from the liberal nonprofit.

Going public just days after the 40th anniversary of the Greensboro Massacre, in which Klansmen and Nazis killed five communist labor organizers at a North Carolina public housing complex, the SPLC Union is invoking the legacy of anti-racist workplace organizing in the deeply anti-labor South.

"Without unions we would not have weekends, paid time off, healthcare, safety requirements and a number of other workers' rights that we often take for granted," the organizing committee wrote to VICE. "We believe in the power of collective bargaining and hope to lay a foundation that will ensure equal rights, respect and dignity for all workers—particularly in the Deep South where a surplus of right to work laws and a shortage of collective bargaining power put workers at risk of discrimination every day. We hope that our decision to unionize will help rekindle the flame of labor organizing across the Deep South."

Frequently, union drives at nonprofits are met with laments from the bosses and management that, while they are sympathetic to workers' concerns, the money simply isn't available to address them. According to the Washington Post, the SPLC's endowment grew to more than $470 million in 2018 as yearly contributions more than doubled after the 2016 election to $132 million. "One of the biggest challenges facing the Center is that it is an old-guard institution that has seen an enormous increase in funding and rapid expansion of staffing following the election of Donald Trump," Nick Martin, a freelance journalist and a former investigative reporter at SPLC, told VICE. "With so much new blood in the building, management there is having to face the fact that it can't keep doing things the way it always has. It can't ignore sexual harassment, gender and race disparities, and low morale. Many of the changes that you've seen this year... are because of workers agitating in informal ways. [Unionizing] will help formalize some of those things and give workers a bigger say in the direction of this important institution."

In March, SPLC fired its co-founder, Morris Dees, amid allegations that he had touched multiple women inappropriately and made sexualized, racialized comments about women of color. (Dees has denied any wrongdoing.) Just before news broke that Dees had been fired, the Los Angeles Times reported, about two dozen employees sent a letter to management and the board of directors expressing their concern that "allegations of mistreatment, sexual harassment, gender discrimination, and racism threaten the moral authority of this organization and our integrity along with it." Shortly after Dees, Richard Cohen, the nonprofit's president, announced that he was resigning. "Whatever problems exist at the SPLC happened on my watch, so I take responsibility for them," he wrote in an email to employees. The organization's long-time legal director, Rhonda Brownstein, resigned the same day.

According to the union's organizing committee, focusing on the conduct of any particular individual, no matter how egregious, would be misguided. "A change in leadership in the Spring opened the door for much-needed transformation within SPLC. A super majority of Center staff agree that having union representation is one way for us to make sure employees are meaningfully engaged in determining what the future looks like at SPLC," the committee told VICE. "This is not about Morris Dees, Richard Cohen or any other one person. We want to make sure the SPLC embodies the principles of justice, equity and diversity in the work we do in our community as well as within our own workplace. We believe collective bargaining will help us uphold those values."

In the aftermath of Dees and Cohen's departures, as the New York Times and the Washington Post published investigations detailing the allegations, a number of former staffers reflected on their experiences at the organization, often focusing on the contradictions between SPLC's public commitment to racial justice and the segregation of its own workers. As Bob Moser, a journalist formerly employed at the Center, wrote for the New Yorker, "Nothing was more uncomfortable than the racial dynamic that quickly became apparent: a fair number of what was then about a hundred employees were African-American, but almost all of them were administrative and support staff—'the help,' one of my black colleagues said pointedly. The 'professional staff'—the lawyers, researchers, educators, public-relations officers, and fund-raisers—were almost exclusively white."

The union will include all such workers. Per the organizing committee, the proposed bargaining unit "includes but is not limited all employees working in administration/finance, communications, creative, Civil Rights Memorial Center, development, digital, donor services, information technology, Intelligence Project, legal, marketing and Teaching Tolerance." HR and managerial employees, as well as guards and supervisors, will be excluded.

In response to VICE's request for comment, the SPLC provided a copy of an email sent to staff by Lecia Brooks, whose title is chief workplace transformation officer. In the email, Brooks wrote that she and Karen Baynes-Dunning, SPLC's interim president and CEO, had "briefed the Board about the petition, and in that conversation, we reaffirmed our values as a new leadership team: diversity, equity, inclusion, justice and as much transparency as permitted by law. Those values will drive this process as they drive our work every day."

"Karen reminded the senior team that we have a long history of partnering with unions in our legal work. This history informs our commitment to supporting all employees’ right to organize, and we welcome an open election process here at SPLC," Brooks wrote.

"We hope leadership will respect the wishes of its dedicated employees and voluntarily recognize our desire to have union representation so that we may have a deep and lasting impact on the Center," the committee told VICE. "However, we are prepared to see our union organizing drive through to the end by winning an election, if necessary."