EXCLUSIVE: A U.S. Marine Used the Neo-Nazi Site Iron March to Recruit for a ‘Racial Holy War’

November 8, 2019At least three members of the U.S. military were registered users on the influential neo-Nazi forum Iron March, according to an analysis of an anonymous data dump from the site this week. And one of them, a Marine, was apparently using Iron March to try to recruit people for a fascist paramilitary group he wanted to launch in the U.S.

VICE News and social analysis agency Storyful verified the identities of three of the posters, but dozens more on the forum claimed to have military experience.

Antifascist activists published files on Wednesday containing the screen names, emails, IP addresses, posts, and direct messages from hundreds of people who were active on Iron March between 2011 and 2017. Storyful and VICE News verified the identities of three men through tracing their emails, linked social media accounts, and social posts. Two are active in the Marines; one left the Army in 2017. They all used the Iron March to discuss their neo-fascist ideologies.

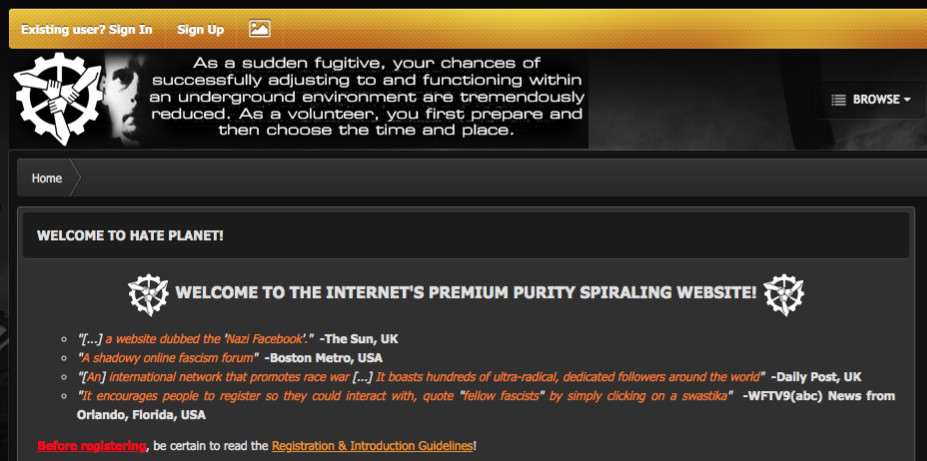

The site, which was active between 2011 and 2017, was affiliated with some of the most dangerous and hard-line neo-fascist groups in the world.

Atomwaffen Division, a notorious neo-Nazi group linked to numerous murders in the U.S., was formed by people who connected on Iron March. The co-founder of banned British neo-Nazi terror group National Action was an Iron March site admin. The forum is also linked to neo-fascist groups internationally, including Ukraine’s Azov Battalion, Greece’s Golden Dawn, and Italy’s CasaPound.

“Everyone likes to talk the talk but in reality won’t die for their blood and soil.”

The use of Iron March by servicemembers is just the latest troubling example of extremism in the ranks, and once again calls into question the thoroughness of its background checks and policies around radicalization.

One of the three servicemembers joined the Marines in 2018 and is currently in the 2nd Marine Division. In the space of about two years before he enlisted, he posted more than 170 times in Iron March. He also attempted to recruit people from the site to the unnamed fascist paramilitary group he was hoping to start in the northeast.

“Not too many people around here are militants,” he wrote under the screen name “Niezgoda.” “Everyone likes to talk the talk but in reality won’t die for their blood and soil.” (“Blood and soil” is a neo-Nazi slogan.)

He also bragged that his record was “clean as a whistle.”

“I’m friends with the police. Most of my revenue goes into equipment for myself and my group,” he wrote. “I’m not the type of person to show up at rallies or brawls…. But in the instance where we have a RaHoWa [“Racial Holy War”] or some shit, I’m going to be a n----r’s worst nightmare.”

Lt. Col. Lyle Gilbert, who handles communications for the 2nd Marine Division, confirmed that the man is active duty.

“We were unaware of these alleged activities,” said Gilbert. “We will fully investigate this matter, and should these alleged activities be substantiated as a result of that investigation, the subject Marine will be held fully accountable for his actions.”

The second servicemember, an Alabama-based rifleman in the Marine Corps, joined Iron March in January 2017. Four days later, he asked Brandon Russell, a founder of Atomwaffen who was imprisoned for stockpiling explosives, about the neo-Nazi group’s chapters in the South.

In exchanges on the forum, Russell insisted that the rifleman read “Siege,” the manifesto of the notorious U.S. neo-Nazi James Mason, which explicitly calls for white supremacists to carry out acts of terrorism and was widely championed within the Iron March community. Describing it as “required reading,” Russell suggested they meet face-to-face. The man later posted that he was reading the book.

That Marine rifleman, who posted under the username “ImperialGrunt,” also interacted with the fellow Marine who sought to create a paramilitary group on Iron March. When the latter asked others on the board if they had found “anybody else with our views” in the forces, the rifleman replied that he had. “In my unit, there’s another guy who could’v[e] easily been a grand wizard [in] the local Klan.”

Responding to another user, he said: “Lots of guys in the military become red pilled. Seeing first hand how little the government actually takes care of its fighting force, much less its citizens is more than enough for many. And if that's not enough, killing some sand n----rs does the rest.”

That rifleman — who was last active on the platform in July 2017, four months before it was taken offline — also gave advice on military training, and spoke of his own martial abilities, claiming to have “pretty decent training in marksmanship, urban and conventional fighting, weapons.” He also discussed his plans for after he left the Marines, writing that he’d considered becoming a private military contractor, possibly in Syria: “[B]ut all you’d be doing is helping Muslims fight Muslims.” In another post, he wrote that “at some point” he intended to run for public office.

The Marines confirmed that the rifleman is a Selected Marine Corps Reserve Marine, and said that they were investigating the circumstances surrounding him. “Bigotry and racial extremism run contrary to our core values,” said Maj. Roger Hollenbeck in an email to VICE News. “The Marine Corps will take the appropriate disciplinary actions if warranted.”

The third soldier identified as an Iron March poster wrote about a dozen messages on the site in 2012. According to his social media accounts, the man served in the U.S. Army as an air defense artilleryman from 2009 to 2017.

In one discussion on the board, the artilleryman outlined his background and political views in response to questions posed by the co-founder of the British neo-Nazi group National Action, who was also an Iron March admin. In 2016, National Action was proscribed as a terrorist organization, and became the first far-right group to be banned in Britain since World War II.

READ: The obscure neo-Nazi platform linked to a wave of terror.

The artilleryman wrote that he didn’t identify as a Nazi but rather a fascist. “I view myself as a variation of 1920's Italian Fascism. I view it as a template, to be modified to work within the context of 2010's USA.” The Army did not respond to a request for comment by deadline.

The three men’s ideologies and public association with self-described Nazis demonstrate, once again, that the military is failing to keep extremists out of its ranks.

In September, a soldier stationed in Kansas was arrested for allegedly sharing bomb-making materials online and planning to blow up the headquarters of a national news network. Earlier this year, the Huffington Post exposed seven members of the U.S. military as part of the white nationalist organization Identity Evropa. In February, a member of the U.S. Coast Guard was arrested and accused of stockpiling weapons and plotting a “race war, with the goal of establishing a white homeland.”

“In my unit, there’s another guy who could’v[e] easily been a grand wizard [in] the local Klan.”

There’s also documented overlap between Atomwaffen and the U.S. military. Last year, ProPublica identified three active-duty military members, and three veterans, who were involved with Atomwaffen. One of them, Vasilios Pistolis, a Marine, bragged online that he’d “cracked three skulls open” during the violent Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville, Virginia, in August 2017. After ProPublica’s report, Rep. Keith Ellison (D-Minn.) wrote a letter to former Defense Secretary Jim Mattis asking for information about what the Pentagon is doing to screen recruits for extremist ties.

This is not a new problem — and the Department of Defense has tried to address it many times over the years.

All military recruits are required to undergo psychological and health tests and fill out a lengthy questionnaire that asks whether they’ve ever been a member of an organization “dedicated to terrorism,” one that advocates for violence, or commits violence with the goal of discouraging others from exercising their constitutional rights. But the form relies heavily on recruits’ self-reporting.

Capt. Joseph Butterfield, the communications officer at Marine Corps headquarters said they have a “multi-layered policy-based approach to screening new and potential Marines for aberrant thinking and behavior.” Prospective recruits undergo several one-on-one interviews with officers at different levels of command. Their tattoos are “screened for content to ensure it is not indicative of a gang or extremist affiliation.” Finally, recruits and candidates are observed by a team of drill instructors, Butterfield said.

The first explicit safeguards against extremism in the ranks came in 1988 when then-Secretary of Defense Caspar Weinberger ordered military personnel to cease participation in white supremacist organizations.

Seven years later, three neo-Nazi skinheads who were also U.S. soldiers were accused of committing two racially motivated murders, prompting an investigation by a Pentagon-led task force. The task force concluded that there were “indications of extremist and racist attitudes among soldiers.”

In response to the findings, the military decided to expand its policy against extremism to give more discretion to commanders to report their underlings’ ideological beliefs. In 2000, the Department of the Army released specific instructions telling military personnel how they should comply with the anti-extremism policy.

“The Marine Corps is clear on this: There is no place for racial hatred or extremism in the Marine Corps,” said Capt. Butterfield. “Those who can't value the contributions of others, regardless of background, are destructive to our culture, our warfighting ability, and have no place in our ranks.”

Cover: Rehearsals of American Army troops (1st Infantry Division, 173rd Infantry Brigade Combat team, 7th Army Training center, 10th Combat Aviation Brigade, US Air Forces Europe, US Naval Forces Europe, US Marine Forces Europe) took place at the Satory military base in Versailles, France, on July 9, 2017. Photo de Nicolas Messyasz (Sipa via AP Images)