Human Rights Activist Allegedly Targeted With NSO Malware Says His Life Is ‘Hellish’

October 10, 2019Hackers likely working for a government targeted two Moroccan human rights activists with malware made by the controversial Israeli surveillance vendor NSO Group, according to a new report by Amnesty International.

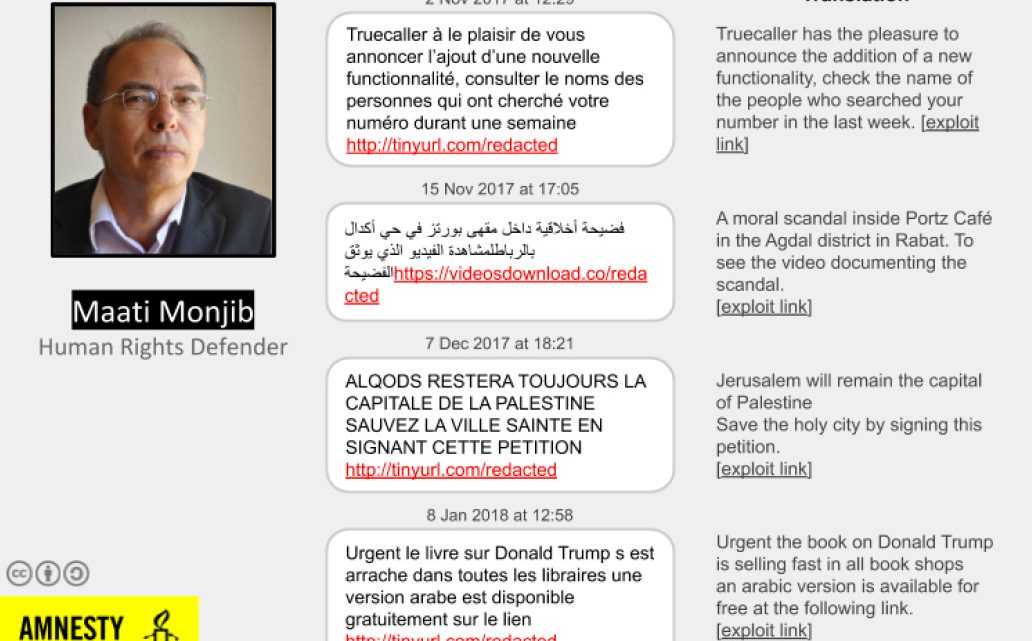

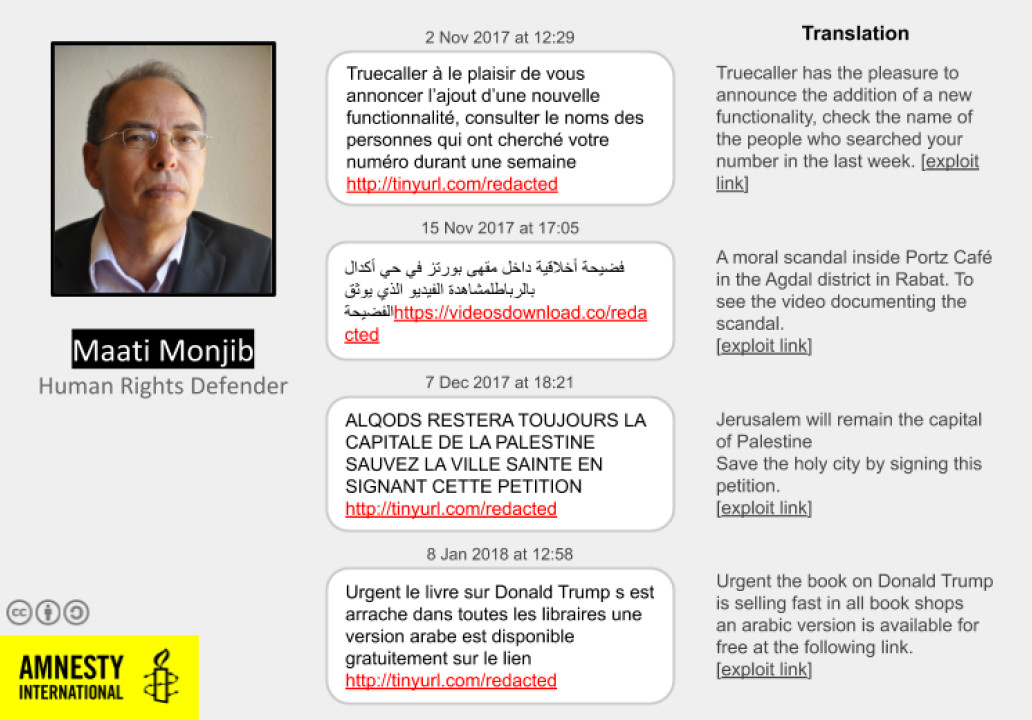

In the report, researchers from Amnesty detail a series of attacks against Maati Monjib, a historian and journalist, and Abdessadak El Bouchattaoui, a lawyer who represented a group of protesters in Morocco. Since 2017, the two men received a series of text messages containing links that pointed to infrastructure previously attributed to NSO Group by Amnesty as well as the digital rights organization Citizen Lab. The researchers said that the links, if clicked, were designed to silently install NSO’s Pegasus spyware on the targets’ phones.

Pegasus is a surveillance software made by NSO Group. In the last few years, security researchers have found evidence that countries such as Mexico, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates have used Pegasus to spy on journalists, human rights activists, and dissidents.

For Amnesty, these attacks are yet another example of how governments are using sophisticated surveillance technology to harass and intimidate dissidents and human rights activists.

“Subjecting peaceful critics and activists who speak out about Morocco’s human rights records to harassment or intimidation through invasive digital surveillance is an appalling violation of their rights to privacy and freedom of expression,” Danna Ingleton, Deputy Director of Amnesty Tech, said in a press release.

Monjib told Motherboard that in the last few years, “physical surveillance and then electronic surveillance have transformed my life to a hellish one.”

“They want me to feel insecure, they succeed in that but only from time to time. But I’m under pressure in every minute of my life. I won’t surrender,” he said in an online chat. “They are powerful, I want to show them I’m determined.”

Have a tip about a hack or a security incident? You can contact Lorenzo Franceschi-Bicchierai securely on Signal at +1 917 257 1382, OTR chat at lorenzofb@jabber.ccc.de, or email lorenzofb@vice.com

A spokesperson for NSO Group said that the company investigates “reports of alleged misuse of our products.”

“While there are significant legal and contractual constraints concerning our ability to comment on whether a particular government agency has licensed our products, we are taking these allegations seriously and will investigate this matter in keeping with our policy,” the spokesperson said in an email. “Our products are developed to help the intelligence and law enforcement community save lives. They are not tools to surveil dissidents or human rights activists.”

NSO Group is one of a handful of companies that sell spyware and hacking tools to governments all over the world. The company says it only sells to law enforcement and intelligence agencies. Morocco’s mission to the United Nations, its Consulate in New York, and its Embassy in Washington, D.C., did not respond to a request for comment via email.

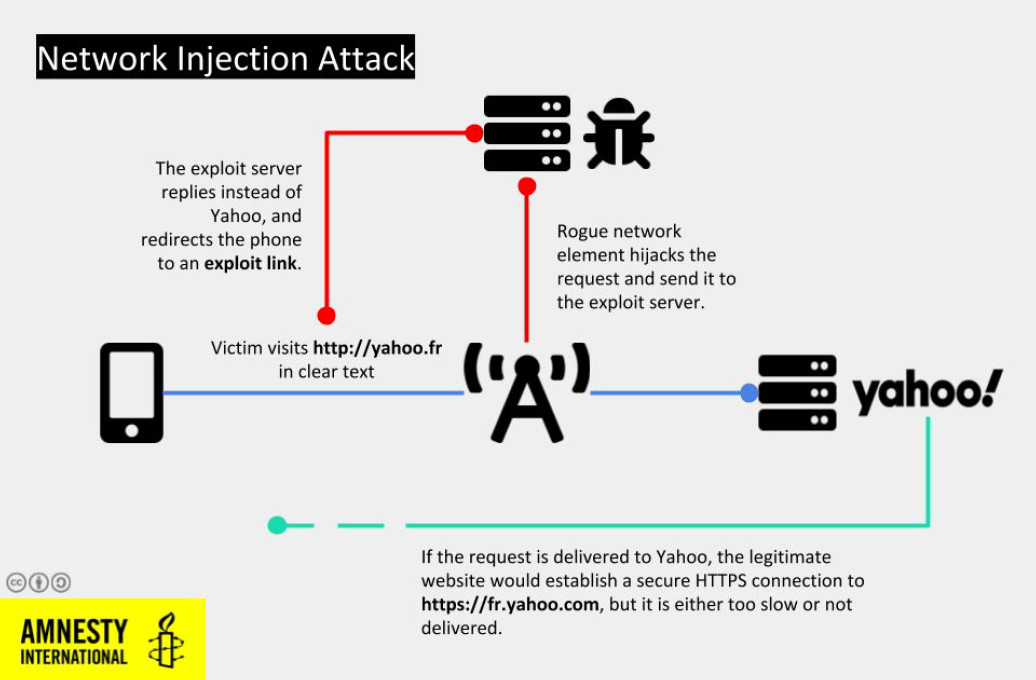

Amnesty researchers also found evidence of a more unusual and stealthy type of hack, known as “man-in-the-middle,” or network injection attack. In this type of attack, hackers who have control over internet infrastructure manipulate and intercept web traffic to redirect visits to legitimate websites to malicious ones, infecting the targets with malware.

Earlier this year, Monjib attempted to visit the French version of Yahoo’s website typing Yahoo.fr on his iPhone’s Safari browser. Instead of being directed to the official site, the browser sent him to a different site that was likely set up to install malware on his phone, according to Amnesty researchers, who believe that at least in one occasion Monjib’s phone was successfully hacked. Amnesty researchers were able to spot evidence of this by inspecting Monjib’s browsing history.

Amnesty is not certain that these man-in-the-middle attacks were also performed with NSO Group’s technology, but some circumstantial evidence points in that direction. First, the network injection attacks came following the malicious SMS attacks. Second, NSO allegedly offers this kind of capability to customers, according to a product brochure that was leaked as part of the Hacking Team breach.

“It is important to document what types of offensive capabilities are being used against civil society, in order to properly strategize with at-risk individuals what can be done to protect themselves,” Claudio Guarnieri, one of the Amnesty security researchers who investigated these attacks, told Motherboard. “This type of attack is hard to identify and prevent, and human rights defenders from Morocco and their support networks should be informed of what they might be up against.”

Subscribe to our new cybersecurity podcast, CYBER.