Ring Told People to Snitch on Their Neighbors in Exchange for Free Stuff

August 9, 2019Ring, Amazon’s home security company, has encouraged people to form their own “Digital Neighborhood Watch” groups that report crime in exchange for free or discounted Ring products, according to an internal company slide presentation obtained by Motherboard.

The slide presentation—which is titled “Digital Neighborhood Watch” and was created in 2017, according to Ring—tells people that if they set up these groups, report all suspicious activity to police, and post endorsements of Ring products on social media, then they can get discount codes for Ring products and unspecified Ring “swag.”

A Ring spokesperson told Motherboard in an email that the program described in the slide presentation was rolled out in 2017, before Ring was acquired by Amazon. They said it was discontinued that same year.

“This particular idea was not rolled out widely and was discontinued in 2017,” Ring said. “We will continue to invent, iterate, and innovate on behalf of our neighbors while aligning with our three pillars of customer privacy, security, and user control.”

“Some of these ideas become official programs, and many others never make it past the testing phase,” Ring continued, adding that the company “is always exploring new ideas and initiatives.”

Ring did not specify how many people the company showed the slide presentation to, and under what circumstances. However, the presentation predates the existence of Neighbors—Ring’s “neighborhood watch” app, which launched in May 2018, shortly after Ring was acquired by Amazon.

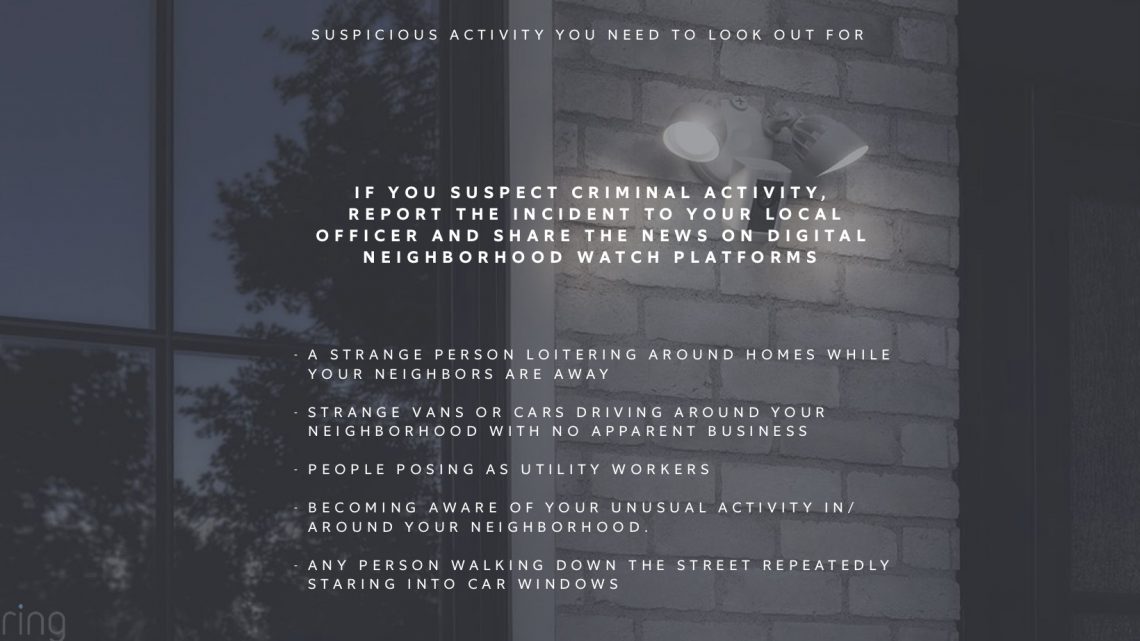

The slide presentation, provided to Motherboard by a source, but also stored publicly on Ring's website, demonstrates that the company has a broad definition of “suspicious activity,” and encourages all suspicious activity to escalate to calling the police. It also shows that Ring’s marketing strategy centrally includes building a network of surveillance facilitated by private residents choosing to surveil themselves and their neighbors.

All Digital Neighborhood Watches were assigned a “Neighborhood Manager” contact at Ring who answered questions as needed and helped groups invite local police officers to “enroll” in their watch.

According to the presentation, if a Digital Neighborhood Watch solved a crime with the help of a local police officer, watch members received a $50 discount off any Ring product. The presentation also encouraged people to report all "suspicious activity," including loitering, "strange vans and cars," "people posing as utility workers," and people walking down the street and looking into car windows.

Got a tip about Ring’s work with homeowners associations and community groups? We'd love to hear from you. You can contact Caroline Haskins securely on Signal on +1 (785) 813-1084, or via email at caroline.haskins@vice.com.

Motherboard has reported extensively on Ring’s cozy relationship with law enforcement. The company has worked with police to organize package theft sting operations in at least five U.S. cities, convinced cities to pay up to $100,000 in taxpayer money for community discounts on Ring cameras, and partnered with at least 225 law enforcement agencies.

However, this slide presentation reveals that Ring actively recruited private citizens to simultaneously promote Ring products and serve as private informants to local police. This has allowed Ring to position itself as a private facilitator of surveillance and policing.

Chris Gilliard, a professor of English at Macomb Community College who studies digital redlining and discriminatory practices enabled by data mining, said that he thinks the slide presentation is “dystopic.”

“It speaks to the way that [Ring] will use any tactics at their disposal to sell more product and continue to build a web of surveillance over communities,” Gilliard said. “Although the [company] deploys the language of ‘sharing’ and ‘community’ in discussing how to build the ‘neighborhood watch,’ the first step is not to build community but to buy a Ring. This is the tell.”

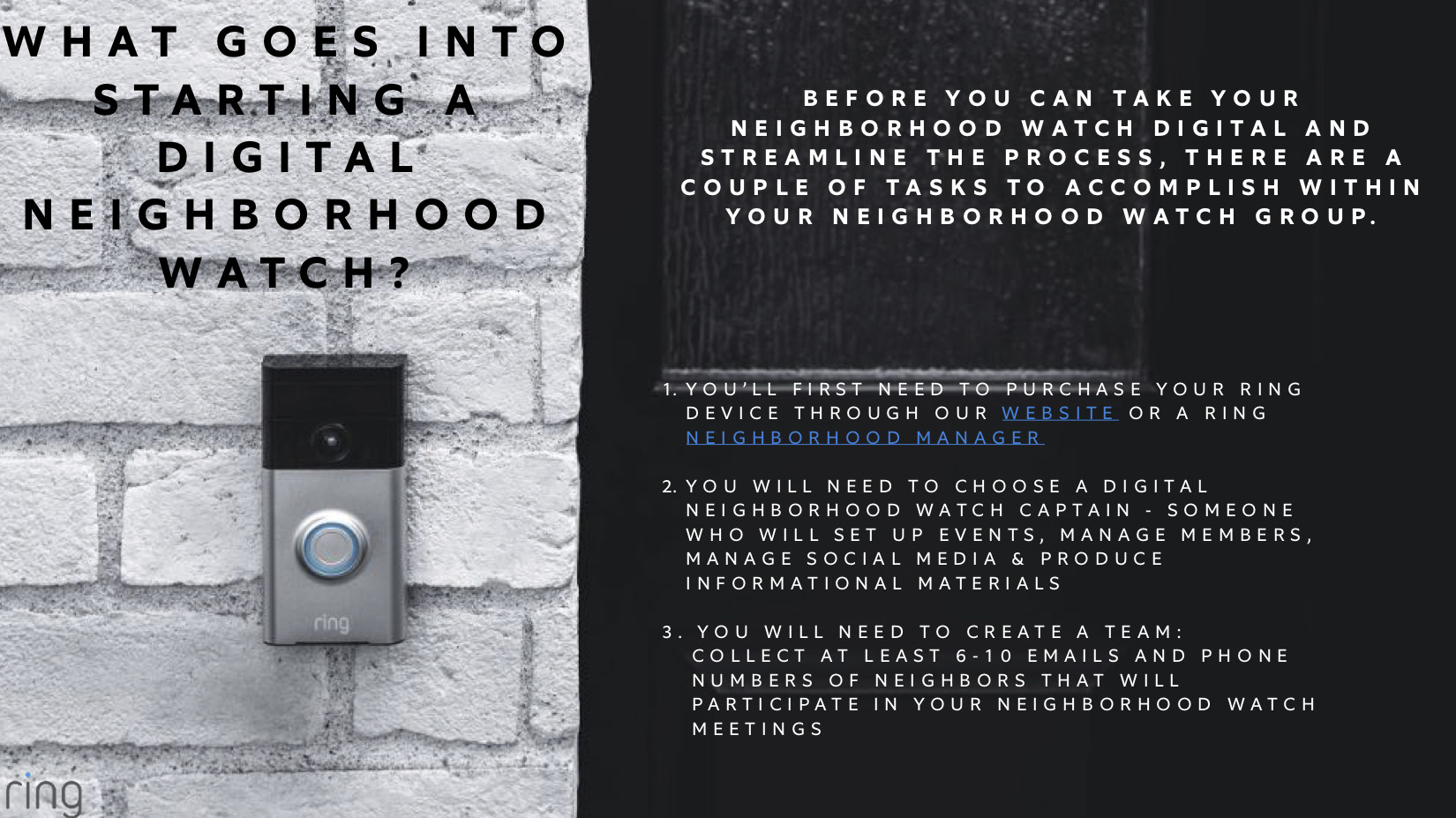

The slide presentation claims that there’s three initial steps to creating a Ring “Neighborhood Watch”:

Purchase a Ring product.

Choose a “Digital Neighborhood Watch Captain” responsible for setting up events, managing members and social media, and making informational materials.

Create a team of 6-10 people that will participate in Digital Neighborhood Watch meetings.

Delores Jones-Brown, a professor of criminal justice at John Jay College of Criminal Justice, said in an email that the presentation is “disturbing.” She also noted that the requirement to buy Ring products will affect the composition of any Digital Neighborhood Watch.

“It has a decidedly middle-class and conservative bent,” Jones-Brown said. “It presupposes people have the resources to purchase and maintain the Ring products and monitoring system and presupposes that there is enough collective efficacy in the neighborhood to organize and maintain a watch program.”

Then, according to the slide presentation, the Digital Neighborhood Watch was supposed to make a Facebook group, distribute promotional flyers to members, and get in touch with local police officers. From there, the Digital Neighborhood Watch is instructed to plan meetings and set internal goals. These goals are centered around the promotion of Ring products and working with police

Ring outlines a 4-month “milestone” progression that Digital Neighborhood Watches should follow:

- Month 1: Organize a Digital Neighborhood Watch event and post video from the event on social media. Ring claims that all attendees will receive promo codes for Ring device purchases.

- Month 2: “Convert 10 new users by downloading Ring app and receive free swag for all users.” The document doesn’t specify what this swag is.

- Month 3: “Solve a crime with the help of our local police officer and receive 50% off any product.”

- Month 4: “Blog about Ring app in a positive way on personal Facebook and/or promote Ring devices in Neighborhood Watch Facebook page.” People who did this received unspecified free swag upon providing a screenshot of the posts to Ring.

Gilliard said that these milestones treat policing “like a video game,” ignoring the fact that police scrutiny often puts people’s lives at risk—especially among people of color and other marginalized groups.

“It seems to incentivize reckless behavior,” Gilliard said. “This is dangerous and irresponsible and is going to result in tragedy.”

Jones-Brown added that Ring's definition of “suspicious” people and activity puts people of color at risk.

“It is troubling because of all of the recent incidents in which police have been called on people of color who are not engaged in crime but who appeared to white residents to be ‘out of place,’” Jones-Brown said.

The presentation later says that members of the Digital Neighborhood Watch should take a “proactive” approach to crime and report all “suspicious activity” to police. It says that people should “learn what is normal and not normal in your neighborhood.”

Motherboard has uploaded the full presentation to Document Cloud.

According to Ring’s Community Programs page, Ring does not only partner with public entities like police departments and law enforcement. The company also works with private organizations, including homeowners associations and community groups.

A “Community Partner Program Terms” page on Ring’s website states that the company provides discounts on Ring products to these groups.

“You will receive a promotional flyer from Ring that indicates the dollar amount of the promotional code,” the terms page says. “The offer begins and ends on the dates and times specified on the promotional flyer. The promotional flyer will also provide instructions on how to redeem the promotional code.”

Ring declined to disclose how many homeowners associations and community groups the company works with today.

Private community groups shown interest in using Ring products for surveillance in gated communities, according to a NextDoor post emailed to police, which was obtained by Motherboard.

“By offering these incentive programs Ring is essentially creating digital bounties,” Gilliard said to Motherboard. “After Trayvon Martin’s murder, I would hope that companies would be more responsible than to encourage citizens to act as vigilantes, but unfortunately that doesn’t appear to be the case.”

All of the documents that informed this article are now public and viewable on Document Cloud.