The List of 2,000 Journalists the Video Game Lobby Doxed Is the Last Thing It Had to Offer

August 5, 2019The flagging fortunes of E3 (the Electronic Entertainment Expo) have been an annual conversation topic in games media for the past few years, with causes being variously identified as a changing media landscape, shifting priorities among platform holders, and the rise of massive video game fan conventions. Until this weekend, it had never occurred to me that the real culprit connecting all these issues could be the Entertainment Software Association (ESA), the increasingly antiquated trade organization that runs E3.

But fuck-ups can be clarifying. This weekend, when word got out that the ESA had posted on the E3 website a plain-text Excel spreadsheet with the names, addresses, and phone numbers of journalists who registered for E3 last year, I wasn’t actually surprised. I was initially shocked at the idea that the organization that administers E3 could be so reckless with anyone’s personal data, but my next thought was that of course the ESA would do this. It’s an organization built for around the politics of the 1990s, and E3 still feels like it is still designed for the media and retail markets of the the same era. In the face of all those changes, the ESA has reacted like an organization whose foremost priority is to keep the gravy train running. The completely careless and unnecessary distribution of a list of media members’ personal information was a pure expression of the ESA’s indifferent and extractive stewardship of E3.

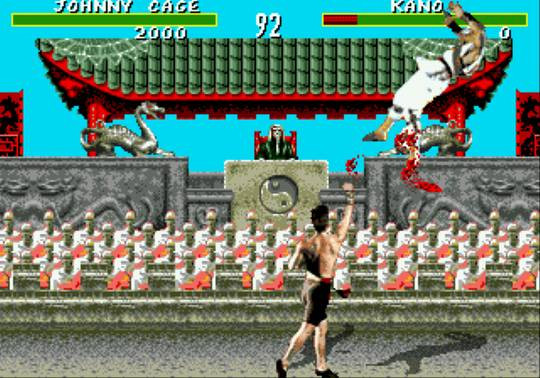

The ESA is first and foremost a lobbying and advocacy organization. But crucially, its roots lie in the issues and controversies of the 1990s, when video games first emerged as a major economic and cultural force and was immediately greeted by hostile and frequently ignorant US politicians who were convinced they represented a new and novel threat to the morals of children. For the next decade and more, the ESA existed to forestall legislative threats both to its freedom of expression and to the industry’s bottom line. And also to operate E3, arguably gaming’s most notable trade show for much of its existence. This bizarre mix of missions never really made sense, but the industry stumbled into it as it broke free of the Consumer Electronics Show and so the arrangement has been inherited by tradition rather than reason.

Politically, the ESA became the collective face of the industry’s fight against the moral panic of the 1990s, when violence in video games became an easy, low-stakes issue for politicians to demonstrate a commitment to “values” without alienating any meaningful voting bloc. But as games emerged as an increasingly powerful cultural economic force, the issue lost much of its potency. The ESA successfully created a self-regulation system in the Entertainment Software Rating Board (ESRB), and the novelty of games wore-off. The high-water mark of the ESA’s political activity was probably its work around Brown v. Entertainment Merchants Association in 2011, a Supreme Court case which affirmed that video games enjoyed First Amendment protection, and put to rest the fear that a hostile Congress might one day impose some form of regulatory censorship on the games industry.

We still see, even to this awful day following an awful weekend of mass shootings, conservative politicians casting about for these familiar straw-men to excuse their own complicity with the cost of doing firearms business in America. Both the GOP and Trump returned to scapegoating video games alongside mental illness in the wake of the shootings in El Paso and Dayton. It’s just clearer now that this is just a socially acceptable way to say “I’d fill a mass grave with shooting victims rather than risk having pro-gun voters turn-out to defeat me.” This is the kind of familiar battle that the ESA got good at fighting, but of course the stakes are lower each time. The “blame video games” tactic is an obvious smokescreen, and no longer a good-faith policy proposal.

But “us-against-them” nature of the sides have never been as clear cut for the ESA outside of those issues. If the ESA’s lobbying against reactionary politicians had largely succeeded in making people forget that it was fundamentally an organization designed to represent publishers rather than developers or players, the ESA and particularly its long-serving (and now former) president Michael Gallagher found ways of making clear the group’s allegiances and, in the end, its cynicism.

The ESA’s stance on piracy was as hard-line as the notorious recording industry’s lobby group, the RIAA. It suggested economic sanctions for piracy and gray-market game sales, and it advocated for aggressive enforcement and punishment for pirates themselves. The ESA advocated for the invasive and far-reaching Stop Online Piracy Act, which imagined significantly restructuring the United States’ jurisdiction over key parts of the internet to protect intellectual property the behest of mostly corporate rights-holders. The ESA eventually dropped its support for the bill, when its defeat was already assured.

Since then, the ESA has largely been without a signature issue. When we spoke to then-president Gallagher last year about working conditions and unionization, he suggested that these were problems the labor market could and probably would solve via competition. His successor distanced the ESA from the issue entirely and suggested it’s something individual companies will have to sort out for themselves. Now the ESA’s most notable priorities appear to be fighting the pathologization of gaming, and making the world safe for companies who want to sell loot boxes.

These are not the kind of black-and-white issues that raise much of a rallying cry, either among industry professionals or among players. There are business and design trends in video games whose ethics are much more debatable than, say, craven politicians blaming games for violence.

Then there is the fact that the ESA did its best to be friendly with the Trump administration and to soft-pedal criticisms around blatantly discriminatory measures like the Muslim ban. In 2017 it also loudly applauded the Republican tax cuts, beloved of and immediately relevant to corporate boards and c-suite executives though probably not quite so large a deal to anyone outside those narrow groups. As Patrick Klepek pointed out in the conclusion of his own piece covering this history, and explaining the line the ESA was trying to walk with the Trump administration: “In the end, it’s about money.”

I think that’s almost right. I think for the ESA it’s been about easy money. Which brings us to what happened this last week with E3.

For all the lobbying and public-facing advocacy work the ESA does, much of its money has historically come from E3. In a piece for Variety about the organization’s internal strife in the wake of Gallagher’s departure last year, Brian Crecente cited a 2016 tax filing that put E3 at 48 percent of the organization’s annual budget.

But E3 is an asset of rapidly diminishing value. Built to service the needs of retailers, a newstand’s worth of enthusiast magazines, and perhaps to get a modicum of attention from mainstream news and entertainment outlets. E3 is a trade show set-up to serve a pre-broadband world. In an era where game trailers can be disseminated around the world within minutes, and gameplay video can be streamed live by just about anyone, the “hands-on” and “first look” experiences that E3 offered are inestimably diminished.

The ESA seemed to realize this when it opened E3’s doors to the public, but it’s not a show for the public. It’s not fun in the way that PAX, or Eurogamer Expo are fun. Those conventions (now both operated by ReedPop) are first and foremost places where people can hang out and always find something to go, see, or do. E3 has long lines for underwhelming demos. In 2018, a “Gamer Pass” to the whole show cost $250, which gives you an idea of the value the ESA places on a product it has never bothered to develop.

Opening the show to the public does not seem to have secured the show’s future. Sony pulled out of 2019’s E3, following EA and Activision out the door.

Part of E3’s dilemma is that it’s no longer necessary for companies to talk to the press to reach their fans, when they can just go the fans themselves (or to pay-to-play influencers who do an impression of fans). If the marketing opportunity that E3 represented is no longer such an amazing marketing opportunity, then what is it that the ESA can sell people?

The answer is a spreadsheet that the ESA posted publicly to its website. On it are the names, outlets, addresses, and phone numbers of thousands of journalists who had their credentials approved to attend E3. Fortunately, and almost certainly because I procrastinated over registering, I am not on that list. Many, many of my colleagues are.

The publication of such a document would be irresponsible in any industry. In games, five years after GamerGate basically shredded conventions of privacy and distance for games journalists and particularly women in games criticism, it’s something worse than that. But I found myself wondering, as I tried and fortunately failed to find my own name within the file, what this was for, and why it had been published.

You always know when you give a convention your personal info that a lot of it is going to end up in someone else’s hands, such as public relations people whose literal job is to connect with media. It’s just that most PR reps who see such lists are smart enough not to make use of anything more invasive than email. In other words, a lot of private information of mine does end up in strangers’ hands, but I trust those strangers to be professional and responsible. That might be naive, but it’s what lets me put it out of mind long enough to sign up for a press pass.

The E3 list was something else. It was just the raw export of every scrap of information journalists gave when they registered. There was no redaction and, most unbelievably, it was just posted on public webpage for anyone to download. But in a way, it also made explicit how the ESA perceives the value of the media that attend its show. It revealed that increasingly, what the ESA is selling is not the media coverage around E3, but the direct access to media. So they made up a list of people that someone might someday want to cold-call, or send a weird tchotchke to out of the blue, complete with the place you can send it.

E3 and the ESA share a common heritage: there was a moment in time when games were just big enough to require their own political activity and their own trade show, but were not yet big enough for most of their major companies to mount those efforts by themselves. The ESA and its show typify a time when games were a subculture that had clear collective interests and the illusion of shared identity.

The ESA is still not set up to imagine or engage with the world since the 1990s and early 2000s. Politically, the most significant issues in and around the industry are ones that the ESA, with its foremost allegiance to publishers, cannot credibly get involved in. The “gamers versus the world” narrative of the 90s that made the ESA a household name among games media and their audience curdled into 2014’s GamerGate, when that shared identity was weaponized to awaken the latent reactionary movement among young men who play video games. The ESA (like a lot of important institutions in games) largely ducked the controversy, apparently only condemning GamerGate when the Washington Posts’ Hayley Tsukayama directly asked for a statement.

The ESA is an organization that’s been overtaken by just about every economic and political reality that taken shape since 2000. It remains an organization built to take dues money from members to win fights with political lightweights over issues that relatively few people care about, and to put on a massive annual trade show for magazine editors and writers from around the world, and purchasing agents from countless brick-and-mortar retailers. That world is gone, and the ESA has had over a decade to react to it. They have repeatedly failed to do so, which has brought us to this last, dismal coda to 2019’s underwhelming E3.

The ESA has behaved like organization bent on extracting the last bits of scrap value from its listing flagship, found a few last corners to cut, and ended up doxxing a huge portion of its attendees, many of whom have spent the last five years pointing out the massive privacy and safety concerns that game journalists now face. That is disastrous news for the future of the ESA or E3, but then again, it’s an organization that only really lives in the past.