‘Hotline Miami’ Showed the Futility of Ultra-Violence as Critique

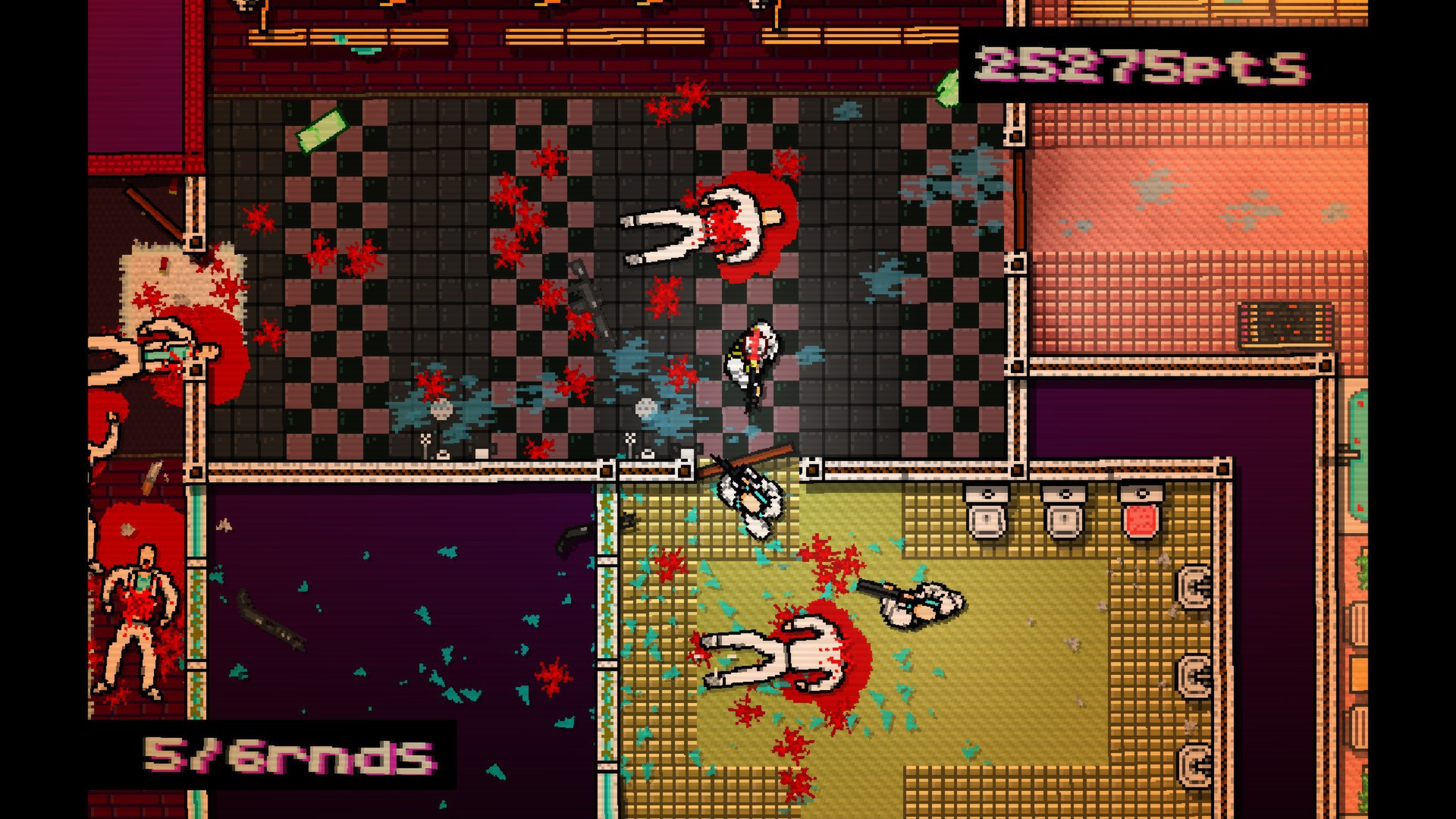

August 2, 2019It’s hot as hell outside, too hot to pay attention to anything for more than a few minutes at a time, and that’s the perfect context for Hotline Miami. Replaying just last week, I found myself abstracting murders out to a math problem. Rotate here, shoot off screen, hide behind this door, throw that shotgun, grab that knife, empty that magazine, avoid that window, fire through that window. It all flows out into abstraction, sublimated under the power of game design that makes us start working in patterns and stop recognizing what those patterns are doing.

And, strangely, there’s no discomfort. There's supposed to be. There used to be.

When it came out in 2012, Hotline Miami sold itself on two things: blood and difficulty. It was built around the basic principle that you and your enemies both died in a single hit, which fueled a game loop of quick death, reconfiguration, and then eventual success. Eurogamer even coined a new term for it: top down fuck-em-up. It might be telling that the term remains rarely useful in the lexicon of games, but the phrase renders something in the raw. You’re fucking things up. You’re separating blood from bone and splattering the world in front of you as you control the mask-wearing Jacket as he murders various people at the request of anonymous callers on his home phone.

Reviewers honed in on the gore across the board. The IGN review claimed that the killing was so common that it turned into inanity. Chris Plante at Polygon wrote that the game made him feel like “an empowered homicidal maniac.” The PC Gamer review found the game’s honesty, that this character is just killing, to be refreshing in a world of games that constantly justify their violence through revenge plots and the like. Critics even actively worked through how the game felt when they were riding the line between the joy of gameplay and the strange feeling of digital mass murder.

This was by design. Co-developer Jonatan Söderström contextualized that violence before the game’s release as something that was supposed to create discomfort in the player. “I feel that in a way it's a little bit irresponsible to portray [the violence] as something stylish, cool, or funny when it's really not,” he told The Verge. “So we tried our best to make it look discomforting.”

This was in line with broader trends. The violent games of the 1990s like Doom or Mortal Kombat were playing to teens who were after a little blood and gore. The violence debates of the 1990s, including the ones that made it to Congress, functionally mirrored previous concerns about music from the decade before. It was a gut check for the industry, and after coming out unscathed there was a doubling-down on the thrill of naughty stuff through the end of the millennium. The exploding enemies of Quake came along and took over while the cultural rebellion flair Marilyn Manson and South Park dominated music and television. In the time since, all of these have become defanged, rote presences in our culture, a kind of standby production that is as predictable as it is boring. They were shocking, and then they weren’t.

The mid-2000s saw the rise of the Grand Theft Auto franchise and “edgy” content. Chain wallet aesthetics and skateboard punks ran the world. Burly men with chainsaw guns and cold-hearted operators did bad things, and the audience wasn’t supposed to have complicated feelings about them.

Violence changed registers in the early 2010s. What violence did in games shifted slightly. It was not about the gross, smiling, chunky shock of an aesthetic basically borrowed from Pulp Fiction or the splatter right out Aliens. When violence was center stage, it was there to communicate grittiness. Call of Duty Black Ops features a scene where the player tortures a man by putting glass in his mouth and then punching him over and over again. This is meant to communicate seriousness, depravity, and a grim political realism of doing what has to be done to win the fight. It should make a player feel bad. In 2010 I did feel bad, and in 2019 I feel bad watching it.

That’s the discomfort that Söderström is trying to produce in Hotline Miami. The game turns this subtext into explicit subtext via a conversation with a spectral rooster that makes it clear that Jacket’s acceptance of anonymous calls and jobs that ask him to kill indiscriminately are unforgivable. He asks if we like hurting other people, and this is supposed to unnerve the player. But who is made uncomfortable? Under what conditions? Game critic Liz Ryerson wrote about the violence of Hotline Miami at release and made it clear that what pushes a player’s buttons when it comes to the violence in the game is not that it exists but that it can become absorbed into a competitive structure. It is possible to get so into the zone that you stop thinking about the images in front of you and focus exclusively on the inputs.

Yet “Do you like hurting other people?” became a meme that is just as ironically flexed as everything else on this cursed earth. And any given thread about the topic is going to wax and wane between taking the sentiment about violence seriously and treating the whole thing like a crass joke that one of the game’s NPCs might make.

I remember feeling the same weird things that all of the reviewers and critics had back at release. I know what it felt like to feel strange when it came to what this game “made” me do. The critical move and the preachy criticism of Spec Ops: The Line in 2012 asked players to look in the mirror and investigate why they were playing these games that were marketed to them and that they paid money for. Players were asked to do things and then fingers were waggled when they did them.

In the early 2010s, violence could become a shorthand for seriousness. Recent Tomb Raider titles have used impaling, crushing, and an overall destruction of Lara Croft’s body to signal that their world is grim and dangerous. Resident Evil VII doubled down on what horror does best by giving us an antagonist who can be sliced and chainsawed infinitely, showing us that even the most extreme violence in this game will never be enough. God of War hinged its entire plot around critical moments of shocking violence in which characters, turning what was essentially a pulp beat ‘em up series into a game about fatherhood simply by honing in on how violence is done and who performs it. The original gameplay trailer for The Last of Us from E3 in 2012 is the perfect example of the violence-as-seriousness paradigm: we know the game is doing something real because it cuts to a title card after shotgunning someone in the head.

I have the feeling that we’re on the verge of another shift. The last substantial The Last of Us Part II trailer has all the hallmarks of the serious violence games from the past decade: someone’s arm is smashed with a hammer and there are brutal executions. But it also seemed that the general reaction mostly mirrored IGN’s response: Why? What is this extreme violence being used for? While IGN’s video really doubles down the past decade of violence-as-seriousness rhetoric, I largely agree that the trailer demonstrates the exact limits of what violence can do for us right now in games.

If The Last of Us Part II’s upcoming violent journey through the post-apocalypse is going to feel like a flashback from the last ten years, perhaps that means games are due for another shift in how they portray and discuss violence. But what form will violence take once games transcend how we think of it now? Will it become more limited in scope or scale? What is the limit point of cruelty? Whose head must be smashed to turn the head of a player, or hell, a critic in our time?

Players and critics are attuned to these constant shifts in the game world, but attention never seems to make its way to violence unless we’re defending our right to it or suggesting that it has gone beyond that pale. I hold out for thinking seriously about violence, whether it is the context of Mafia III’s hyperviolent encounters or Fallout 76’s astoundingly cynical nukes or the personal, catastrophic precision of the Hitman games. And what I think we should take from the Hotline Miami moment is that violence does, in fact, change registers.

It’s tempting to say that Hotline Miami was either unnecessary or that it ran interference while other violent games went on their merry way. It’s also tempting to say that it made us weary of finger-wagging and provided a green light for on-screen eviscerations if only because they allow us to escape the moralizing. What's perhaps most notable about the game's treatment of violence is that all of this is true, but it's all dependent on the context into which you place the game.

The regime of violence that Hotline Miami was released into might have been important, and therefore Hotline Miami felt important. Playing it today, at a time when "seriousness" communicated through violence has run its course, and in 2019 Hotline feels both passe and like an emblem of a forgotten regime. Its critique has been mooted, yet a critique of violence remains as necessary as ever. What will emerge to take its place?