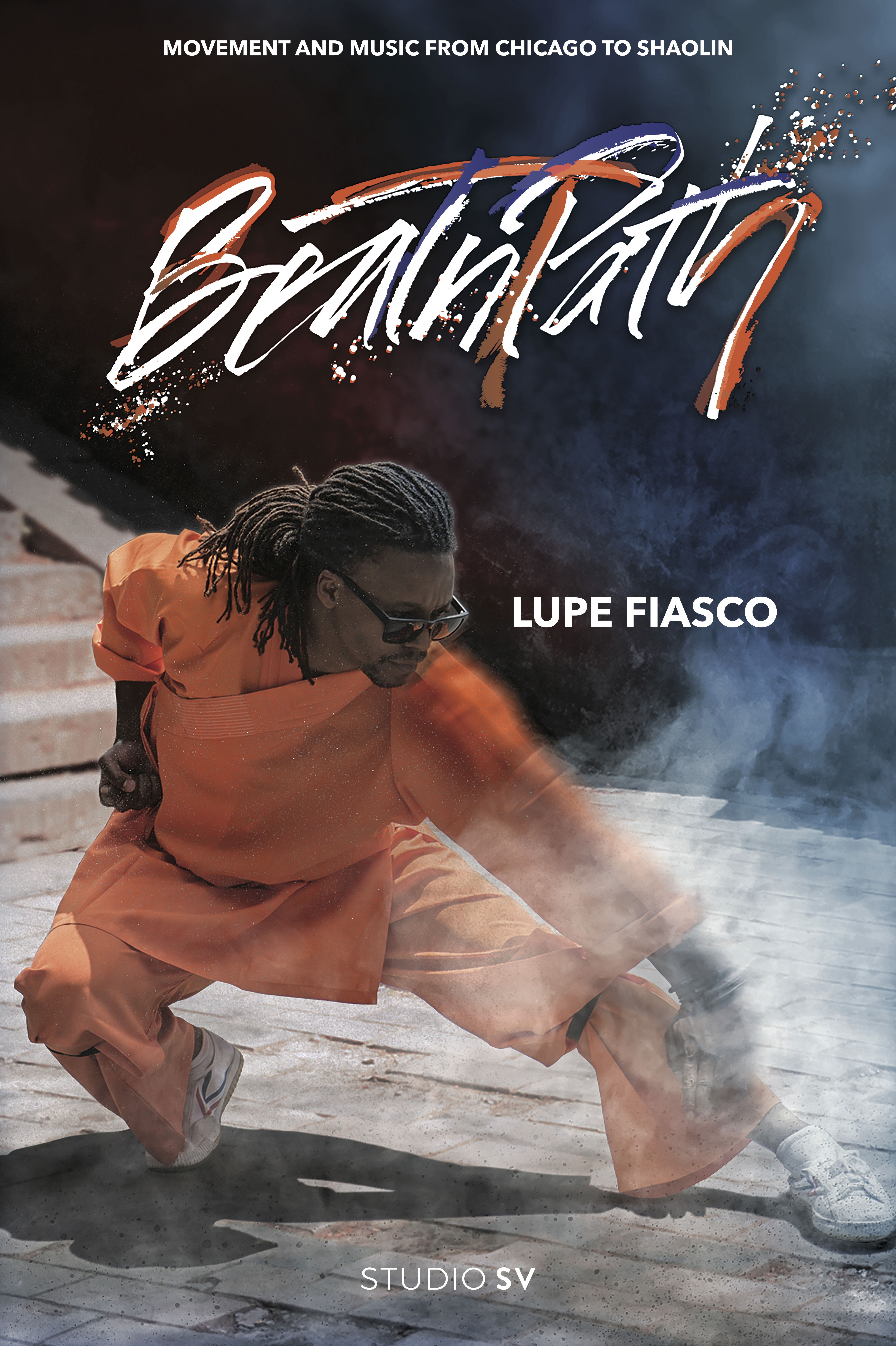

Lupe Fiasco’s New Documentary Series Explores His History in Martial Arts

July 2, 2019Across his long and prolific career, Lupe Fiasco has always found a way to defy labels. When he emerged in the hip-hop avant-garde in the mid-aughts, his approach was idiosyncratic. He sought to take ownership of his work and he was open about using interests other than rap as creative outlets—he blogged, skateboarded, and was outspoken about his love for anime. In a time before it felt normal to do so, he was open in his political views, embraced dramatic storytelling in the form of rap operas like The Cool, and of course, had a relentless dedication to wordplay and thought-provoking bars.

Which is to say, he's hard to pin down. His projects have taken a lot of forms in the last decade, and he's showed off a lot of different passions. So it's not surprising that this week he's emerged with something totally new. On Monday, he premiered Beat N' Path, a docu-series he produced with Hong Kong media maven Bonnie Chan-Woo about his travels across China to learn about different forms of martial arts. In an interview, Lupe explained that martial arts have always been a part of his life.

Lupe's father was a military veteran and engineer who was fascinated by martial arts, and raised him with a deep appreciation of the history, spirituality, technical skill, and beauty of martial arts. Hip-hop has had its share of martial arts fans over the years, but this background uniquely positions Lupe to host the show. We sat down with him last week in VICE's Brooklyn office to learn more about the series and the unique role that martial arts have played in his life.

NOISEY: You're a Grammy award-winning musician, a Street Fighter champion, a semiotician, an Aspen Institute fellow and a businessman. How did we miss the fact you've been doing kung fu since you were three?

Lupe Fiasco: Well, in some ways, you've only got so many chips. You can't show all your chips, there's certain things that are not relevant. The story is, my family business is the martial arts. My father had martial arts schools in Chicago for 40 years. He started doing martial arts when he was in his early teens. He could have been world judo champion if he didn't hurt his shoulder... or as his sensei said, "if he had trained a bit more." He had an array of students from all over the world, and he had 8 black belts.

So martial arts was our life. Martial arts and army surplus stores, because he was a military veteran. I could count to 10 in Japanese before I could count to 10 in English; that's how close our training was to us. We had sensei and students training in the backyard, weapons all over the house. The first gifts my father gave me as a child was a djembe drum and a samurai sword. I got my first black belt, I think I was 11 or something like that.

So you were one of those kids.

It was so massive to me, but not a whisper of it when I turned 17 and I wanted to be a rapper. It was Wu-Tang Clan, Jay-Z and Nas, Chino XL and Canibus, and here we go. It wasn't relevant to that space to rap. Some people kind of laugh at it, right? It's weird just in the Black space. It's weird just being a Black person that does martial arts in the Black community... kids would pick on you and you'd just beat the brakes off 'em... but that was just what it was, right? People didn't understand it. Some people still feel, even to this day... when I first did the footage of me doing the samurai sword on my Instagram, people were like, "What the what?" People say "You Black. You not supposed to be doing that. Why you trying to be Japanese? Why you trying to be Chinese?" The first language I heard was Japanese, as related to martial arts. It has been with me since the inception, literally, since I was born. And I still do it to this day. It powers a lot of my discipline, my thoughts, the way I look at things, the way I examine, the way I absorb. It all comes from the martial arts.

So I'm guessing you listened to a lot of Wu-Tang growing up. What did it feel like to you, when you first started experiencing hip hop that brought these two parts of your life that seemed separate together?

I wasn't super blown away, because we knew all those movies they pull samples from! I know Super Ninjas, or Kid With the Golden Arms. That seemed pretty cool, it was more conceptual references than anything else. But back then we didn't know that Wu-Tang did kung fu for real! We know now that RZA did Shaolin kung fu, and still does Shaolin kung fu. But back then, we didn't know. For us, it was like backpack rap that had a flair to it. I mean, we knew Wu-Tang from the wudang sword and all that stuff. But when you listen to the content of the music, they're not always talking about doing kung fu. It was dope though, to see, but it wasn't as crazy as it may seem, because we were legitimately doing martial arts.

What would you listen to while you were training?

My father, in the classes, he would play hip-hop. He played a bunch of Public Enemy, a bunch of N.W.A. He would play music that fit the mood of what we were training. It would be Ravi Shankar one day, and then some random King Sunny Ade the next day. I listened to Dead Prez, not for martial arts, but for Black radical militancy in music. Stic-Man is definitely a martial artist though.

Who else in the hip-hop world is an undercover martial artist?

There's a ton of genuine legit martial artists in the hip-hop space. So Swave Sevah, a battle rapper here in New York, he's a beast. He's a black belt, I think he does Shotokan karate. You see FKA Twigs, she's doing Chinese longsword, like wu-shu sword. Legit, too. Not even like, "I'll play with this for a video," she's legitimately doing it. Stic-Man does martial arts, I don't know to what extent. RZA does Shaolin kung fu. Denzel Curry does martial arts! For real... I think he does kickboxing and kung fu.

Damn, that's quite a list. So can we make a series where we have battle rappers battle and then rap...

And then fight each other? Like chessboxing?

There's enough of them now!

Well, here's the difference. There are ranges of why people get into the martial arts. There are folks who are in it purely for competition and for sport, people who are in it for the history, people who are in it for the well-being and health aspect of it. There are people who are into it purely for play. There are people who are in it for self-defense, or combat. Killing things, not competition. And then there are people who are into it for the historical tradition side of it... and there are people who are in it for the spiritual aspect. A lot of kung fu in the martial arts comes from Zen Buddhism. There are these different energies and you can mix! There's people who are in it for the spirit and the combat, like samurais. Spirit combat—kill you, then pray type situation. Pray about killing you. Pray that I don't have to kill you. Kill you and then have to pray about it. And then there's just pure MMA—don't care about the history or the uniforms, don't know how to tie a belt, just here to compete.

So everything can't be funneled into, "you know martial arts, so let's fight" because you have some people who don't know how to fight, because they never went into it to fight. They may be able to take out the layman, you know, do something sexy to you. But for the most part, people get into it for a range of reasons. You see it in the show, we do tai chi which isn't a fighting art. You stand like this, and punch like this because it helps your liver. That's the story... you stand like this because it helps you balance. So it's like yoga. It's like, "you know yoga? Let's fight!" It's like... c'mon man.

That's a fair point. How did this China trip come about? How are you taking viewers on this journey?

Beat N' Path came about because I was fascinated by China. I had been there maybe once or twice, superficially on the outskirts, mostly entertaining English speaking ex-pats. So I wanted to be there and fully understand the culture. So I just started to go, unannounced, and pop up. Ride the subway, meet the people and challenge some of the misconceptions and adjust some of the biases that came from the West. Expecting kung fu fights to just break out in the streets, or expecting every Chinese restaurant to be amazing. It's like, this isn't Chinese food, it's just food. But the language barrier hits you. You can't rap your way out of this, you can't freestyle, you can't speak Mandarin or Cantonese, so it's a wrap.

I wanted something deeper, a business in China. A mutual friend introduced me to Hong Kong marketing and media executive Bonnie Chan-Woo, who was interested in branching off into developing content around cross-cultural formats. It kind of started as, how can we do a music show with some kung fu in it, but then it turned into a kung fu show with a little music in it. That's where the Beat N' Path comes from. It's me going to different parts of China. Beijing, Dengfeng, where Shaolin Temple actually is, and learning from different masters and the art of different forms of kung fu. We even branched out into bian lian, which is Sichuan face-change opera, which has a lot of kung fu movement in it. Tai chi, pachi, wu shu, Muslim Chinese wu shu. Shaolin kung fu. Learning with masters in their element, in their training halls that are 600 years old. Seeing where Shaolin monks actually stomped—there are holes in the floor from where they stomped for thousands of years.

I see anthropological study across your body of work. Do you feel that art should constantly be exposing people to new ways of thinking and new ways of being?

That should be life. That shouldn't just be art. Life is the goal, that's the header. Everything else should fall from that. That should just be one of the directions of life: you should be interested in pursuing and understanding and opening yourself up to other things. It shouldn't be the responsibility put upon art and artists to do that. I think you should have it in you... regardless. You should want to go out and see the world and be impressed and see things and be challenged and chase your goals. Don't get captured in your own culture for whatever personal, political, or social reasons.

For me, this is normal. This isn't an attempt to be like, "Hey, I need to get back into rap and I'm going to come through this with this weird piece of technology." This is literally me. I was genuinely being astonished, being in these places, feeling these feelings for real. I almost didn't want the cameras to be there in certain instances, to be honest, because it feels so special and it feels so real.

Imran Hafiz is a VICE contributor and Publisher of VIRTUE Intelligence. He doesn’t know kung fu...yet.