Police Are Feeding Celebrity Photos into Facial Recognition Software to Solve Crimes

May 16, 2019Police departments across the nation are generating leads and making arrests by feeding celebrity photos, CGI renderings, and manipulated images into facial recognition software.

Often unbeknownst to the public, law enforcement is identifying suspects based on “all manner of ‘probe photos,’ photos of unknown individuals submitted for search against a police or driver license database,” a study published on Thursday by the Georgetown Law Center on Privacy and Technology reported.

The new research comes on the heels of a landmark privacy vote on Tuesday in San Francisco, which is now the first US city to ban the use of facial recognition technology by police and government agencies. A recent groundswell of opposition has led to the passage of legislation that aims to protect marginalized communities from spy technology.

These systems “threaten to fundamentally change the nature of our public spaces,” said Clare Garvie, author of the study and senior associate at the Georgetown Law Center on Privacy and Technology.

“In the absence of rules requiring agencies to publish when, how, and why they’re using this technology, we really have no sense [of how often law enforcement is relying on it],” Garvie said.

The study provides several real-life examples of police using probe photos in facial recognition searches.

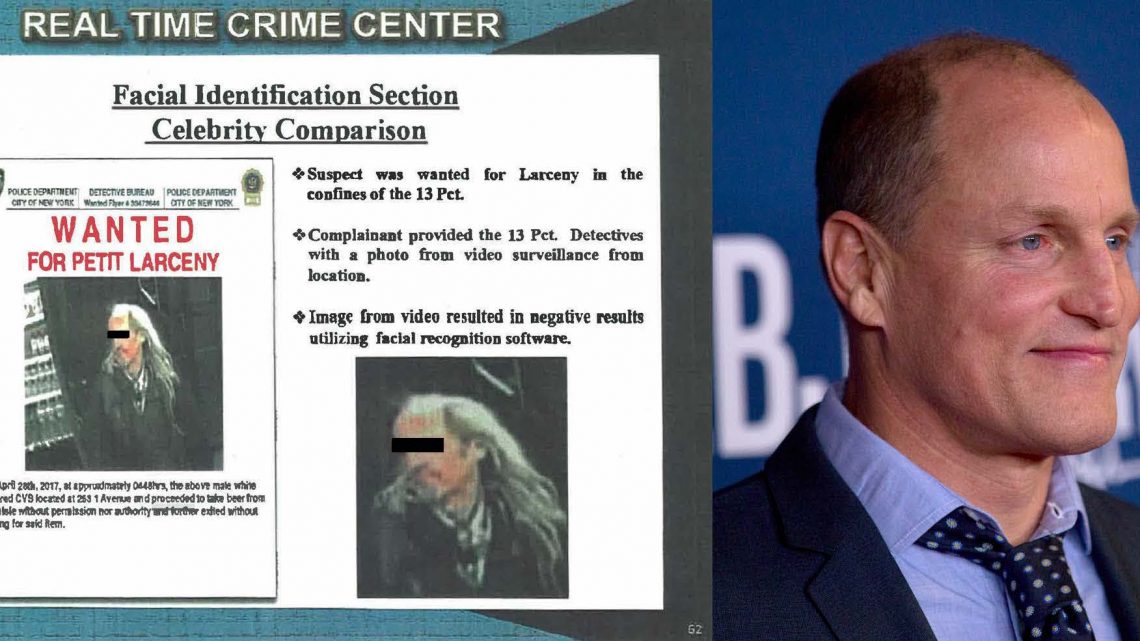

On April 28, 2017, a suspect was caught on camera allegedly stealing beer from a CVS in New York City. When the pixelated surveillance footage produced zero hits on the New York Police Department's (NYPD) facial recognition system, a detective swapped the image for one of actor Woody Harrelson, claiming the suspect resembled the movie star, in order to generate hits.

Harrelson’s photo returned a list of candidates, including a person who was identified by NYPD as the suspect and arrested for petit larceny.

The NYPD also fed an image of a New York Knicks player (whose name was redacted in police documents provided to the Georgetown Law Center on Privacy and Technology) into its facial recognition system in order to find a Brooklyn man wanted for assault.

These are just two cases of police trying to brute force leads from facial recognition technology using dubious images.

NYPD records show that it made 2,878 arrests stemming from facial recognition searches in five years. Florida law enforcement agencies run roughly 8,000 of these searches per month, according to documents from the Pinellas County Sheriff’s Office.

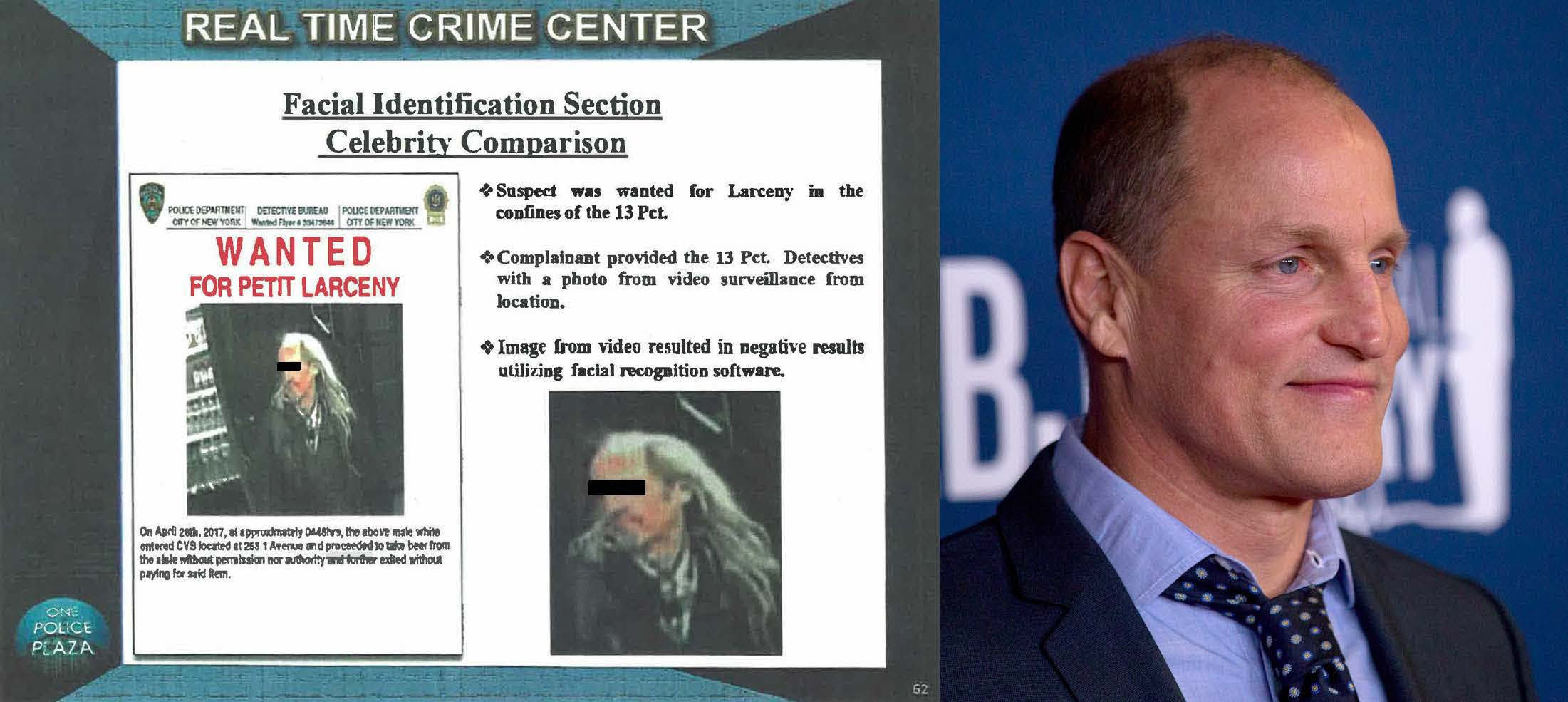

Departments are also using poorly-drawn probe images in facial recognition searches, such as a forensic sketch that was fed into Amazon’s facial recognition software, Rekognition, by police in Washington County, Oregon.

Low-quality and filtered photos pulled from social media are also valid, police guidance documents show, according to the study.

The German facial recognition company Cognitec encourages customers to “identify individuals in crime scene photos, video stills and sketches.”

When artistic renderings don’t work, some companies market software tools that generate composite images. Vigilant Solutions—which has allowed more than 9,200 Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents to access its automated license plate reader database for tracking US residents—lets police create “a proxy image from a sketch artist or artist rendering.” The gist of this technique is to enhance suspect images so that facial recognition algorithms can better match them to people.

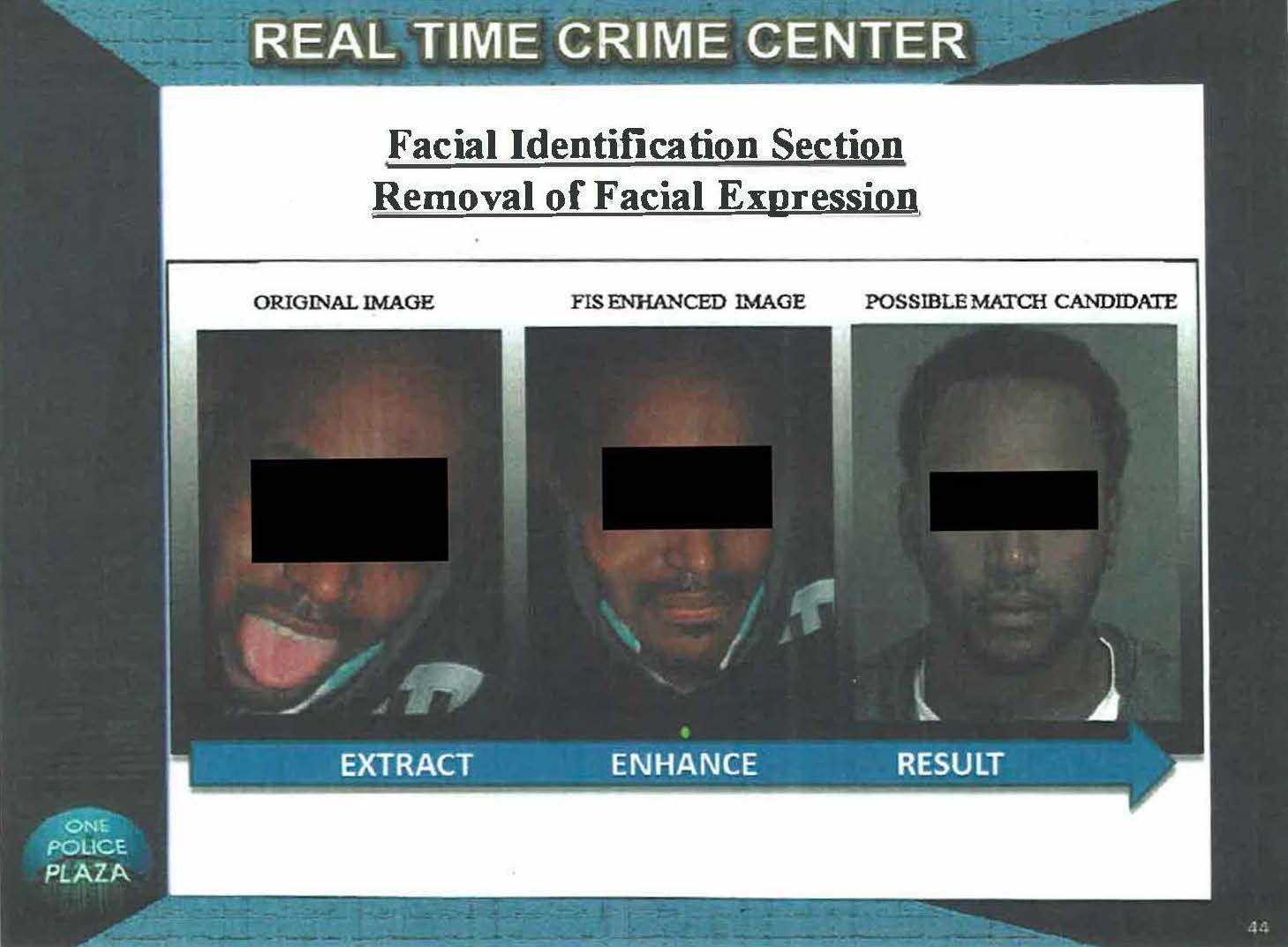

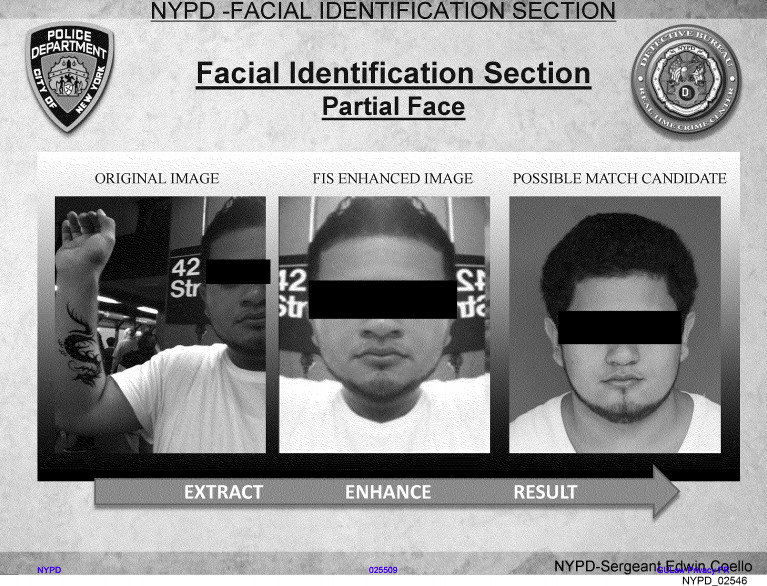

Some editing is commonplace, the study notes, but computer-generating an image can “often amount to fabricating completely new identity points not present in the original photo,” it adds. The digital alterations that police can make appear extensive.

According to a presentation by the NYPD’s Facial Identification Section (FIS), detectives may: replace an open mouth with a closed one; add a pair of open eyes sourced from a Google image search; clone areas of the face; and combine “two face photographs of different people whom detectives think look similar to generate a single image to be searched.”

NYPD and other agencies have also used 3D modeling software to fill in missing facial data, according to the study. This means that a photo showing 60 percent of a suspect’s face could be given a 95 percent confidence rating—a lenience not applied to evidence such as partial fingerprints.

“As far as we know, a court has never weighed in on whether facial recognition produces reliable results,” Garvie said. The reason for this is largely that law enforcement agencies and prosecutors aren’t handing over information about these searches to the defense to be challenged, she said.

“Given the degree to which law enforcement relies on the results of facial recognition searches to make arrests, this in my opinion is a violation of due process,” Garvie added.

Civil rights advocates have objected to the use of facial recognition systems by police given the technology’s lack of accuracy and racial bias.

Several police departments in the US, including those in New York and Los Angeles, have committed to purchasing real-time facial recognition technology, and experts are especially concerned about its potential use if applied to body cameras.

“Facial surveillance makes mistakes,” Garvie said. “On body cameras that may lead to an officer drawing their weapon and using deadly force under the mistaken belief that a person is a suspect or threat to public safety because an algorithm told them it was a match. That’s too risky of an application to ever consider.”