The Indie Publisher Trying to Turn the Mueller Report into a Bestseller

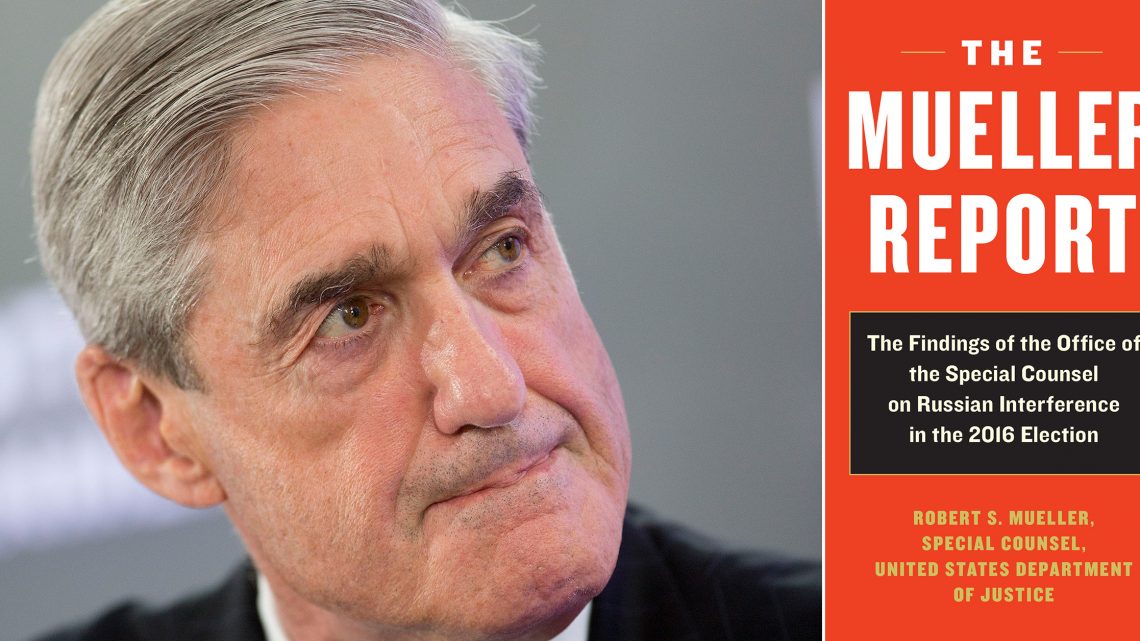

March 27, 2019Robert Mueller's recently wrapped investigation into Russian interference in the 2016 election may not have brought down the president, but at least it will produce a bestseller. So far Attorney General William Barr has only made public his own four-page summary of the Mueller report, infuriating Democrats who want the whole thing to be released—a debate some in the book world are watching very, very closely. Public appetite for a longer report has been growing for months, and perhaps thinking of the massive cultural impact and sales generated by Ken Starr's report on the Bill Clinton scandal in the 90s, multiple publishers have preemptively announced plans to publish the Mueller report.

"As far as prepublication buzz goes," David A. Graham wrote in the Atlantic this month, nothing "can match the expectations attached to the Mueller report."

The Washington Post and Scribner teamed up to publish the report—more specifically, an "e-book within two to three days of the report and the paperback in five to eight days"—all the way back in February. They'll be competing with Skyhorse, whose president and publisher, Tony Lyons, said over email that he plans to release a bound book within seven days of the report's release. (Skyhorse's version of the report will be paired with an introduction by famous lawyer and Trump defender Alan Dershowitz, while the Post's version will include an introduction and supplemental material from the paper's reporters.)

The most recent publishing house to announce it was putting out the report is the independent Melville House—which, having been founded only in 2001, already has a lengthy history of transforming such reports into book form. (Examples include Senate Intelligence Committee Report on Torture, The Climate Report, and Federal Reports on Police Killings.)

VICE called up Dennis Johnson, the co-founder of Melville House, to discuss the process of creating books from these sorts of documents, and why he's selling one with no introduction or additional context.

VICE: When did discussions about publishing Mueller's report begin?

Dennis Johnson: We had been talking about doing this at least a year ago. We got an ISBN, and we designed a cover, and all that. We have a track record of doing a lot of these government reports, and this, of course, would be the biggest one we've ever done. We had our eyes on it from the start. So we've been waiting, too, all this time. I think we're going to be waiting a little while longer, we'll see [laughs].

How quickly could you get the book out until the world, if—whenever—it does go public?

If, say, it dropped tomorrow, I think we could get it out in ten days.

Do you expect it sell well?

Oh, absolutely. We've done very well with these sorts of things, and if you look historically at some of the really big ones, like the 9/11 Commission Report or the Starr Report, those are books that sold in the millions, if you take in all the different editions. And that's kind of encouraging, too: There's good civic interest in these books.

What happens if it's not all made public?

You don't really have a plan, other than to have a team ready. We've done it before, with the torture report, so we know the production issues. You put the printers on alert, the shipper, the warehouses. You have it ready to go. As I said, we've done quite a few of these books, from the torture report to Ferguson and the federal report on the police shooting to the Supreme Court on marriage equality—we just did the climate report in January. We have not only a team ready to go on this, but one that's very excited. They feel this has real meaning. It reminds you why you're in the business of books. You just have to sort of wing it, and use your publishing instincts. And fly by the seat of your pants.

The possible issues are: One, that they don't release it at all; two, that they release it, but it's redacted; and, three, they release it in segments—and so on and so on. It can also be, like, 5,000 pages long. So all the numbers so far, from the three publishers who have said they were going to publish the book, we're all putting up our best guesses.

For us, the trickiest thing would be if they release it and it has a lot of redactions. Because redactions are very hard to replicate properly in a well-made book. And the torture report is a good example of that: When they released the torture report on a Friday afternoon, during the Christmas season, nobody saw it coming, and it was heavily redacted. It was released by the government as a PDF that was barely readable, and it was so badly made it was nearly impossible to do a search on it. So we had to completely remake that document. You can copy out text easily enough, but for a redaction remark, there's no typesetting a redaction. We had to figure out how to recreate that.

How did you?

Well, there's no typeface that has a black square like that. We actually had teams of people literally working around the clock, and we were all sitting there with rulers, measuring character spaces from the original—because if you look at redactions, often enough you can figure out what might have been redacted by the length of the redaction. So we wanted to measure that by character spaces, and that was only doable by hand. That's obviously a slow process.

How long did that project take you, then?

That, from start to finish, was three weeks.

And that wasn't even preemptive, right? Like you literally had no real idea the torture report was coming out?

Nobody knew when it was going to be released, and it was at a terrible time of the year. It's busy time of the year. Stores are filled with books. None of the big houses wanted to do it, and none of us saw it coming—but we made the decision, immediately, to do it. There was a lot of coverage of that, too. We had reporters embedded with us and stuff. It was quite an ordeal. In many ways, we've already had this experience.

The other thing is, it's important for us to make a good book. What we found out with the torture report was that we had to really make it an easy-to-read and searchable digital book, in addition to a print book. You get a certain expanded readership with a print book, which the government will basically only do if you send them a lot of money, like a manuscript of it; otherwise, it's just this thing online that nobody would really read.

When I was a kid, in the 60s and 70s, my parents had the Pentagon Papers in our library, just because they thought it was an important book—so that's, in a sense, why you want a print book. But we also wanted to do a digital book, so that people could really read and use that document. And later on, we heard from all kinds of academics, the ACLU, Amnesty International, who thanked us for making it searchable. It was much easier for them to coordinate and do research. It's important to make these sorts of things right—and there will be a lot of knockoffs.

You're publishing this without any sort of introduction to frame it, unlike Scribner and the Washington Post, as well as Skyhorse. Why?

As the attorney general, William Barr, just showed, it's a mistake to give these things any kind of an apparatus, or a summary, or an introduction. You are digesting it for people, and you're giving it a certain bias when you do that. And we have never done that. We have always believed that the documents should speak for themselves—that the readers should be given the respect that they have the intelligence to comprehend this document, and develop their own thinking about the document. We really feel that we're just doing a public service, and trying to get it out there, and to let people make their own assumptions.

All of the criticism that you're seeing of AG Barr's report now kind of shows you how these things can go wrong. You need the real document. From a publisher's viewpoint, I find it kind of curious, too—because now you've got an edition that's branded by Jeff Bezos's Washington Post, or you've got another one that's branded by Alan Dershowitz, who's a Trump supporter, and why would I get that if I'm not a Trump supporter?

I don't think those are necessarily good publishing decisions. They're certainly not good civic-minded decisions.

So the main differentiation, for you, is that it's a public good, and you're not so much in direct competition with these other publishers?

Absolutely. I think we are publishing the book the best way it can be published—and I'll say that in extent to the format as well. We're very excited to be doing this as a classic American-formatted mass-market paperback.

It's your first one in that formar, yeah?

Yes. This kind of speaks to my personal background: The paperback—part of the reason it developed was to get the book out to a wider audience, in particular children. Making them more affordable to young people, and getting the classics out there. That's what a paperback always represented to me.

If you wanted to disseminate it to as many people as possible, this all seems to me the right way to do it.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Sign up for our newsletter to get the best of VICE delivered to your inbox daily.

Follow Alex Norcia on Twitter.