A Brief, 200-Year History of Humanity’s Love for Laughing Gas

March 8, 2019This article originally appeared on VICE Australia.

In 1799, at a party in a second-story drawing room in Bristol, England, a motley crew of poets, philosophers, scientists, and doctors sat around in their powdered wigs and pantaloons and sucked nitrous oxide from a bag. The esteemed English chemist Humphry Davy—just 20 at the time—owned the lab downstairs, and he organized these gatherings for the express purpose of letting his friends try this newly-discovered, mind-bending dissociative. “Laughing gas,” he called it.

Like many great origin stories of modern-day inventions, laughing gas—also known as nangs, whippets, and nitrous—was stumbled upon by happy accident. Humphry had joined the Pneumatic Institution at Bristol a year earlier, where under his boss, physician Thomas Beddoes, he attempted to isolate gases deemed remedial for tuberculosis sufferers. He and Beddoes isolated oxygen, and shortly thereafter managed to isolate its then-mysterious cousin: nitrous oxide. In the interest of science, young Humphry inhaled the colorless gas. And the rest, as they say, is history.

"He was just astonished to find this incredible wave of euphoria and energy," Mike Jay, a cultural historian who has written extensively about drugs and medicine over the years, told the ABC. "He started leaping around the laboratory, shouting and screaming and laughing… it was a total surprise."

That “surprise” discovery kick-started a turbulent chain of events which, over the months and years to come, would see Humphry diving headlong into mind-expanding research, becoming subsumed by a life-threatening nitrous oxide addiction, and ultimately emerging as one of the most influential scientists of early 19th century Britain.

First though, being the benevolent researcher that he was, he decided to share his new favorite substance with friends, colleagues, and acquaintances at multiple “laughing gas parties” he hosted above his lab. An array of guests—among them the English Romantic poets Samuel Taylor Coleridge and Robert Southey—would show up to the parties, pass a green silk bag around, and huff nitrous from it until they were veritably high.

"It must have been quite like a performance," says Mike, who claims that attendees would shout: "’Give me more, give me more; this is the most pleasurable thing I've ever experienced’” while "[others] were running up and down the stairs and all around the house, saying odd things that they'd forget later."

These parties weren’t strictly for the sake of debauchery, though. Humphry described them as “experiments,” and asked his friends to record their psychedelic experiences as a way to inform his research on the gas. At the turn of the 19th century, he collated their observations on the mind-altering effects of nitrous and published them in a book. The laboriously-titled Researches, Chemical and Philosophical; chiefly concerning Nitrous Oxide, or dephlogisticated nitrous air, and its Respiration was the culmination of Humphry’s research into nitrous oxide: a preeminent scientific document that laid out the gas’ synthesis, its effects on animals and animal tissue, and, most notably, its effect on the human mind. Here are some highlights:

“Oh Tom! such a gas has Davy discovered! Oh Tom! I have had some. It made me laugh & tingle in every toe and finger tip. Davy has actually invented a new pleasure for which language has no name. Oh Tom! I am going for more this evening—it makes one so strong & so happy! So gloriously happy! & without any after debility but instead of it increased strength & activity of mind & body—oh excellent air bag. Tom I am sure the air in heaven must be this wonder working gas of delight.” —Robert Southey

“I felt a highly pleasurable sensation of warmth over my whole frame, resembling that which I remember once to have experienced after returning from a walk in the snow into a warm room. The only motion which I felt inclined to make, was that of laughing at those who were looking at me.”—Samuel Taylor Coleridge

“I feel like the sound of a harp” —an unnamed clinical patient

Humphry’s inquiries into the effects of nitrous historically extended beyond these soirees to various forms of self-experimentation as well. He inhaled progressively larger quantities of the gas, and with increasing frequency, to see what happened when he became more and more dissociated. Then he documented his findings.

“Generally when I breathed from six to seven quarts, muscular motions were produced to a certain extent,” he noted. “Sometimes I manifested my pleasure by stamping or laughing only, at other times by dancing round the room and vociferating.”

Before long he was huffing it outside of laboratory conditions—sitting alone in the dark and breathing in huge amounts of the gas—and eventually developed an addiction. Everywhere he went he dreamed of getting high, confessing that “the desire to breathe the gas is awakened in me by the sight of a person breathing, or even by that of an airbag or air-holder.”

At one point, for one of his self-described “experiments,” Humphry skulled a bottle of wine in eight minutes flat and inhaled so much gas that he passed out for two hours. Another journal entry notes that “Between May and July, I habitually breathed the gas, occasionally three or four times a day for a week together.” Yet even during these periods of heavy bingeing, Humphry observed that “the effects appeared undiminished by habit, and were hardly ever exactly similar. Sometimes I had the feeling of intense intoxication, attended with but little pleasure. At other times, sublime emotions connected with vivid ideas.”

Toward the end of 1799 Humphry went so far as to construct an “air-tight breathing box” in which he could sit for hours on end, inhaling as much nitrous as he could before losing consciousness and having even more intense, “sublime,” and “vivid” experiences. He almost died in this chamber on more than one occasion.

It was through this turbulent, double-pronged lifestyle of debauched partying and self-experimentation, however, that Humphry ultimately came to realize what would become laughing gas’ most commonly exploited benefit. He had reportedly used it as a way to treat his hangover, to some success, but it was when he inhaled the gas to relieve the pain of a toothache that he discovered the medicinal benefits of nitrous.

“It may probably be used with advantage during surgical operations in which no great effusion of blood takes place,” he observed, taking heed for the first time of the gas’ anesthetic effect.

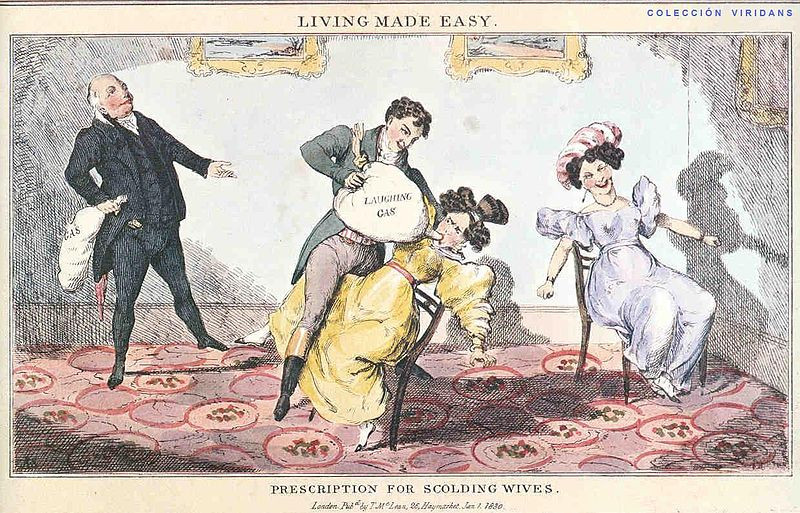

This would go on to become one of his more notable achievements. But the 19th century nang parties that he pioneered along the way were also embraced by the world beyond his lab, as word of nitrous’ euphoric effects spread to London and eventually the United States. People gathered at traveling fairs and carnivals to get high, or watch others get high, in tents with nitrous oxide; the gas being “administered only to gentlemen of the first respectability” and “The object [being] to make the entertainment in every respect a genteel affair."

Humphry’s party-hard lifestyle ultimately seemed to take its toll on his health, and he suffered several strokes before dying in a hotel room at the tender age of 50. But his legacy of laughing gas parties would outlive him for centuries to come. These days, detractors of nangs probably assume that the medicinal gas has been co-opted for nefarious purposes. But history shows that people were huffing nitrous to get high long before they were using it for pain relief.

It was through the tireless, wanton hedonism of Humphry’s laughing gas parties that the drug’s potential as a general anesthetic was finally established—meaning that every doctor, dentist, or patient who’s ever used nitrous as a medicinal substance owes a tip of the hat to the party liaisons of the past. Getting oneself to a place where you “feel like the sound of a harp” was, and always will be, nitrous oxide’s original function.

Sign up for our newsletter to get the best of VICE delivered to your inbox daily.