I Got High to See if I Could Legally Drive Under Canada’s New Impaired Driving Laws

February 27, 2019This article originally appeared on VICE Canada.

When the Canadian government announced its new legal limits for how much THC can be in a driver’s system, my first thought was, what the hell does any of this mean?

I’ve been consuming cannabis for a long time, and I feel like I know when I am and am not good to drive. Beyond that, I’ve been covering the weed beat for years. But I had no clue what two nanograms of THC per milliliter of blood—the legal limit—meant in practical terms, nor could I tell you how much weed I would have to consume to reach that limit. I’ve heard from many Canadians who feel the same way.

So, I decided to make myself a guinea pig and test out the government’s new impairment laws in an attempt to gain some clarity.

But first, let’s get into the nitty gritty of those regulations.

When the federal government legalized weed last October, it also passed a swath of rules around impaired driving caused by both alcohol and cannabis.

The weed impairment laws have created a series of new crimes specifically based on how much THC is in a person’s system when they are driving, also known as per se limits. One of the most important things to remember is there is no definitive evidence linking these THC levels to impairment. The government chose these numbers arbitrarily, and it has admitted as much.

These are the new offenses:

- Having between two and five ng of THC per ml of blood within two hours of driving would be punishable by $1,000 fine.

- Having five or more ng per ml of blood within two hours of driving could be considered a summary or indictable offense, punishable by a fine of $1,000 on the lower end to a maximum of ten years in jail for repeat offenders.

- Having booze and THC in your system (50 mg or more of alcohol per 100 ml of blood plus 2.5 ng or more of THC per ml of blood) would also be a hybrid offense (indictable or summary) and would again be punishable by a fine of $1,000 on the lower end to a maximum of ten years in jail for repeat offenders.

In addition, provinces have implemented their own punishments for weed-impaired driving, which include automatic drivers’ license suspensions and vehicle impoundments if a person fails a roadside test.

A roadside test could mean a standardized field sobriety test—a set of three tasks a driver must complete—or an oral fluid test, which tests saliva to determine if a person has recently consumed cannabis. The government-approved testing device, Draeger DrugTest 5000, can detect THC in a person’s oral fluid for four to six hours. It is set to fail a person who has 25 ng of THC or more per ml of oral fluid.

The device does not say how much THC is in a person’s system and failing it does not indicate impairment. But a fail can trigger provincial penalties, regardless of whether or not a person has more THC in their body than the legal limit under the criminal code.

In order to be charged criminally, a driver who fails one of the roadside tests would need to be taken for a blood test or for an evaluation by a drug recognition expert—an officer specially trained to detect drug-impaired drivers. Failing the DRE evaluation would result in a blood or urine sample being taken.

Various experts and studies have claimed you should wait anywhere from two to 12 hours after consuming cannabis to drive. But many regular and even occasional cannabis users will tell you the effects don’t last nearly that long.

Beyond that, while most people have a rough idea of how many glasses of beer or wine they can drink while still being OK to drive, the government’s legal THC limits are meaningless to the average person. THC can be detectable via blood in a person’s system for a month, and it is stored in a person’s fat cells, meaning it can linger long after a person stops being high. A person’s fat content, metabolism, and the potency of the drug are all factors that could determine how long THC is detectable.

With all this in mind, I decided to conduct an experiment.

I use cannabis both recreationally (to relax) and medicinally, for chronic insomnia. Most nights I’ll smoke the equivalent of half a joint, or take a few drops of THC oil. I consider myself to have a fairly high tolerance. Within an hour or two of smoking a joint—depending on potency—I would feel completely fine to drive. But I wondered if that feeling would match up with the THC limits imposed by the new laws.

Bear in mind: This test is based on me, and the results have no bearing on how anyone else would fare, because our bodies all react to cannabis differently.

The experiment

9:40 AM: Sober driving simulator

Because I couldn’t actually drive a car, I had a company called DriveWise bring their driving simulator to our office. DriveWise provides driver training in Ontario and I figured this would be the closest I could get to actual driving. However, when I tried the simulator out sober, to give a baseline, I immediately crashed into a cop car and later an ambulance. I chalked this up to not being used to the simulator—I found it disorienting.

10:15 AM: Baseline blood test

Before I got high, I wanted to do a sober blood test. I was curious to see if the baseline would pick up any THC since I consume weed pretty frequently and had vaped the night before, but it turned out my baseline had no THC.

10:30-10:45 AM: Vape weed

After that, I headed outside to vape for about 15 minutes. I wanted the experiment to reflect my real life usage, so I wasn’t planning on getting baked out of my mind, but obviously I wanted to feel the effects of the weed. I smoked an indica that contains 20 percent THC, which is on the higher end of the spectrum. My vape chamber’s capacity is about a third of a gram. When I finished, I felt baked, ranking myself at about a six out of ten. Mostly, I just felt a bit looser and more relaxed. In that moment, I wouldn’t have driven.

11:15 AM: Blood test and driving simulator

About an half hour after consuming cannabis, I took another blood test. Then I tried the driving simulator again. I didn’t crash this time, but I was overly slow and I passed by a school bus flashing its lights. But the simulator isn’t a scientific means of measuring cannabis impairment—and you can potentially improve each time just by getting more used to it.

11:45 AM: Standardized field sobriety test

About an hour after vaping, I had a former cop and drug recognition expert Steve Maxwell perform a standardized field sobriety test on me. My high had already depleted considerably. Maxwell said if an officer stopped me in a roadblock and noticed something like the smell of weed or dilated pupils, the standardized field sobriety test could be used “to elevate the suspicion to reasonable and probable grounds for arrest.”

The test consists of three tasks. For each task, Maxwell evaluated me based on a set of “clues” that would indicate impairment. If I exhibited too many clues, that would be grounds for arrest. (Refusing to take the test is grounds for a criminal charge.)

Test 1: Horizontal gaze nystagmus test. Maxwell held up a pen in front of me and moved it around, requesting that I follow the top of it with my eyes, but without moving my head.

Impairment clues: I exhibited two of a possible six clues, according to Maxwell—a “lack of smooth pursuit” meaning my eyes were getting ahead of the pen instead of following it smoothly with my eyes. One clue per eye. Maxwell said that’s normally not an effect of cannabis.

Test 2: Walk and turn test. Maxwell asked me to take nine heel-to-toe steps along a line of tape on the floor. After the ninth step, I had to use one foot to turn around and then take another nine steps back. I was also told to keep my head down and my arms at my side and count aloud during the test. Once I started, I wasn’t allowed to stop.

Impairment clues: Maxwell said I showed two of a possible eight clues—the minimum number of clues for a fail. I used my arms for balance and I stopped walking for more than a couple of seconds after my ninth step. (For the record, I stopped because I was trying to figure out how to maneuver around without lifting my front foot.)

Test 3: One-leg stand. I had to stand straight with one foot raised about six inches off the ground (I choose to raise my right leg) and count aloud by one thousands, staring at the raised foot. My arms had to remain at my side.

Impairment clues: I exhibited two of a possible four clues—I used my arms for balance and I put my foot down.

While I wasn’t completely sober during those tests, I’m still quite confident I would’ve been able to drive. And I wasn’t convinced I would have performed all that much better on these tests dead sober because I find balancing challenging. I also wondered how people with physical challenges or disabilities would fare.

12:15 PM: Blood test

90 minutes post consumption.

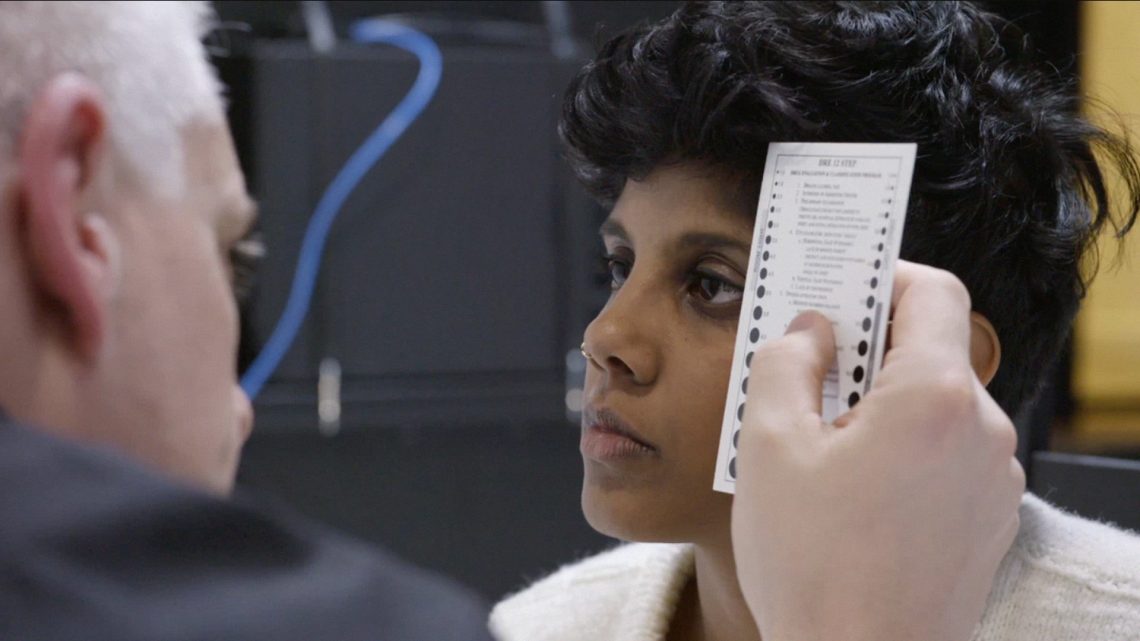

12:35 PM: Comprehensive drug recognition expert test

Maxwell said my performance warranted an arrest at which point I would either have my blood taken or go through a comprehensive evaluation with a drug recognition expert.

My extensive DRE evaluation was about an hour and 45 minutes after I’d finished vaping, and almost an hour after the roadside standardized field sobriety tests. Maxwell said that time lapse would be typical in the real world, as it would take time to get a driver into a police station.

The DRE evaluation involved an interview (I said I hadn’t used any drugs), the three tasks I’d already performed, and a few extra elements such as taking my vital signs and pulse, checking my muscles, looking at my arms for track marks, and examining my pupils in a dark room.

Maxwell determined that I was not impaired.

While I still exhibited a couple of impairment clues—trembling eyelids, putting my foot down once—I was mostly normal.

“I can’t form the opinion that you’re impaired by cannabis right now,” he told me, noting some of the steps aren’t scientifically validated but are more for giving an idea of if somebody is impaired or not.

“You have some clinical signs that you’ve been using cannabis, that’s fine,” he added. “But you’re not exhibiting impairment.”

Maxwell said he believes DRE evaluations are “the best thing that we have right now” to determine if a person is impaired. “At the airport if they want to know if you’re carrying weapons, they put you through the scanner and the machine tells them. Well, we don’t have that for impairment.” His finding was in line with how I felt—no longer high, and fine to drive.

1:15 PM: Final blood test

For the sake of the experiment, I also took another blood test at the conclusion of the DRE evaluation. This took place about two and a half hours after I finished vaping.

Blood test results

So, how did I fare on my blood tests? Well, I never even got close to the legal limit of THC.

The results showed that 30 minutes after vaping, I had 0.5 ng of THC per ml of blood level, which is four times below the legal limit of 2 ng per ml of blood, even though I felt too high to drive. And that was my peak. By the time I took my final blood test, about two and a half hours after vaping, I was back down to .06 ng of THC per ml of blood.

However, the fact that I failed the roadside test means in Ontario I would potentially face a three-day license suspension (which can’t be appealed) and $250 penalty. Those penalties increase upon subsequent offenses.

VICE recently reported on a Halifax woman who has multiple sclerosis and uses cannabis medically. She failed the oral fluid test, after being stopped in a roadblock, having smoked half a joint six hours earlier. But a drug recognition officer later determined she was not impaired. Regardless, her car was impounded and her driver’s license was revoked for a week. If the same thing happens again, she will lose her license for 15 days, and then 30 days in a subsequent case. In Quebec, a driver immediately loses their license for 90 days if any THC is detected in their system.

Again, these results are based on my experience and my body—they aren’t applicable to other people. It’s totally possible that a medical cannabis patient—someone with a much higher tolerance—would have failed the blood tests even if they weren’t high, due to the amount of THC in their system.

Phillip Ajiboro, founder of Windsor-basd Cognizance Labs, is currently recruiting volunteers for clinical trials that will use breath to test the link between consumption and impairment.

Ajiboro, who helped set up my personal mini-trial, said there are limited studies on the link between cannabis consumption and cognition and impairment on a pragmatic level.

“Cannabis users need to know how the various products will affect them,” he said. That information because particularly important with the government’s strict new impairment laws. The laws have kicked in before the public is familiar with factors like THC potency, strains, or edibles versus dried flower versus other types of weed.

“We drastically need more community-based clinical trials that study the impact of different cannabis products, strains, and consumption methods,” Ajiboro said. “Ignorance is not bliss.”

Sign up for our newsletter to get the best of VICE delivered to your inbox daily.

Follow Manisha Krishnan on Twitter.