Let George H.W. Bush and the WASP Establishment Die

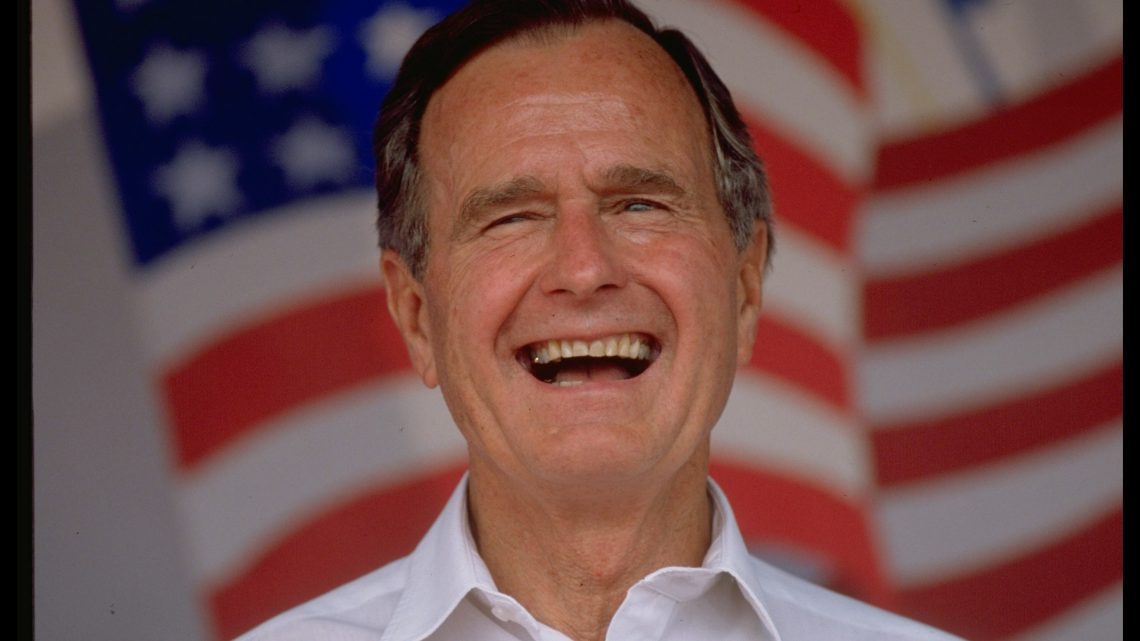

December 5, 2018When ex-President George H.W. Bush died over the weekend, it marked the symbolic, if bitterly contested, end of an era when national leaders were widely regarded as worthy of respect. Many of the tributes spoke of him as an "honorable" man who embodied "a 'kinder' and 'gentler' strain of Republicanism" than the one on offer today, as the New York Times wrote, echoing Bush's own rhetoric. If he was not your sort of hero personally, you might at least have seen in him qualities worth celebrating, from his service as a Navy pilot in World War II to his restrained foreign policy as president to his commitment to working with Democrats.

In many respects he was the best of the "establishment," a nebulous, shifting universe of highly educated, mostly white, mostly Christian, mostly straight male elites who have ruled the United States—in elected office and in other positions of power—for most of its history. In a New York Times column shooting around the internet at high velocity, conservative Ross Douthat expresses the most nostalgic possible vision of what Bush the elder represented: "a ruling class that was widely (not universally, but more widely than today) deemed legitimate, and that inspired various kinds of trust (intergenerational, institutional) conspicuously absent in our society today."

The column generated instant outrage when it dropped Wednesday morning because it's headlined "Why We Miss the WASPS" and because Douthat refers to the establishment by that old acronym. But Douthat also focuses on the stereotypical virtues of the WASP elite: "noblesse oblige and personal austerity and piety," along with "a spirit that trained the most privileged children for service, not just success" and a "cosmopolitanism" that allowed some elites to understand "the non-American world better than some of today’s shallow multiculturalists." What Douthat is arguing for isn't the continued domination of white Protestants; he wants a diverse ruling class that retains the "more pious and aristocratic spirit" that gave us figures like Bush. It's not the worst vision of America, but it's incomplete and ultimately unimaginative.

If there was ever a place to debate elitism and privilege and power, it'd be the Times op-ed section. And the fundamental questions Douthat raises are good ones: When we talk about the people who rule the country (a separate, if overlapping, category from the people the country elects), what features do we want them to have? What makes an elite class virtuous? But when contemplating these questions, we should also grapple with the failures of the WASPs, and why the establishment collapsed in the first place.

In Douthat's telling, the WASPs simply gave up their grip on power, and that was probably a bad thing: "Along with the establishment failure in Vietnam, which hastened the collapse of the old elite’s authority, there was also a loss of religious faith and cultural confidence, and a belief among the last generation of true WASPs that the emerging secular meritocracy would be morally and intellectually superior to their own style of elite." The problem is that glides rather glibly over all the ways this ruling class failed, again and again, until there was no reason for anyone—including its own members—to have faith in it. If the virtues of duty and service Douthat cites seemed a bit corny or cobwebbed, it's because it's difficult to fathom that anyone seeking power in America believes in them anymore.

The Watergate scandal, a signature postwar sign that powerful people weren't especially competent or moral, was arguably handled by the establishment about as well as could be expected. Bush, who was chairman of the Republican National Committee at the time, defended Richard Nixon until deep into the saga, though he eventually urged the president to resign. But even if the post-Watergate era featured a host of campaign finance and pro-transparency reforms, elites didn't stop trying to hide unethical behavior. More than a decade later, the Reagan administration sold arms to the Iranian regime (in violation of an explicit Congressional ban) and funneled the profits to right-wing guerrillas in Nicaragua. The Iran-Contra scandal, as it was known, led to a years-long investigation that only ended when Bush, in arguably one of his worst moments, pardoned six officials caught up in it just before he left the White House. (The question of how closely Bush himself was involved in the affair may never be answered.)

The Reagan era provided Americans with more reasons to regard the ruling class with suspicion. Thanks in part to the anti-labor policies of Republicans, real wages were stagnant, and have mostly remained so since. The country's WASP leadership often ignored problems facing people who didn't look or act like them, as the Bush administration did when it continued Ronald Reagan's legacy of not reacting quickly or strongly enough to the AIDS epidemic. The war on drugs, endorsed by leaders of both parties, sent people of color to prison en masse—Bush accelerated it, calling for “more jails, more prisons, more courts, and more prosecutors.” And neither party came out of the 90s looking especially virtuous—Bill Clinton lied about his affair with Monica Lewinsky, and House Speaker Newt Gingrich, his chief antagonist, was carrying on an affair while going after Clinton with puritan indignation.

The nadir of elite rule came under George W. Bush. If the younger Bush inherited any of his father's blue-blooded virtues, that didn't stop him from presiding over a disastrous war (backed by intellectuals from both parties), botching the response to Hurricane Katrina, and sitting there and watching as the economy imploded at the end of his term. The obstructionism and partisanship—in particular from the Republican side—that marked the Obama era didn't do much to reinvigorate people's faith in the country's leaders, either.

Maybe the elites involved in these scandals and failures of leadership had that sense of duty so highly praised by Douthat. Maybe too few of them did, and that was the problem. But it seems obvious in retrospect that as the WASPy establishment transitioned into a different, less old-world sort of power structure, it continued to ignore the concerns of many Americans, and many of its members were only interested in enriching themselves and retaining power. There's no evidence Americans would have been more trusting of their upper-class cousins had those elites hewn more closely to WASP values—the problem was that so many elites turned out to be corrupt, incompetent, or both.

As Donald Trump has demonstrated, anti-elitism alone won't fix America. Trump, despite his nod to old-world values with his odd fixation on Ivy League credentials, has merely replaced the establishment with a bunch of his family members and cronies, with predictable results. What the country needs is a new crop of leaders with a new set of values. This means a sense of public service and obligation rooted not in class privilege but in civic patriotism. This means a desire to root out corruption that is genuine enough to cut across party lines. This means a willingness to challenge authority as well as assume authority and make hard choices.

The fundamental point of Douthat's column is that there is such a thing as an American ruling class, and it "should acknowledge itself for what it really is, and act accordingly." He's correct about that—some people will always have more power than others to shape the future. But replicating a WASP value system that burnt itself out on a cocktail of foolish wars, corrupt dealings, and economic inequality is taking us in exactly the wrong direction. George H.W. Bush is dead. So is the world he came from. Let them die.

Sign up for our newsletter to get the best of VICE delivered to your inbox daily.

Follow Harry Cheadle on Twitter.