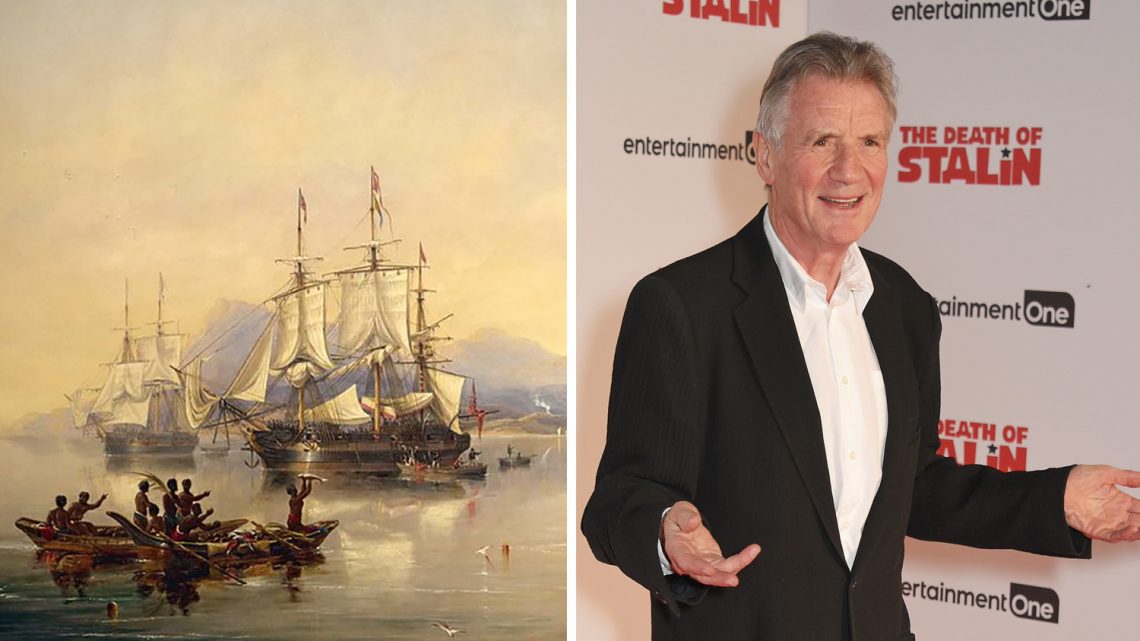

Monty Python’s Michael Palin Explains Why He’s Obsessed with a Mysterious Boat

November 19, 2018“I kind of get recognized as ‘the traveler,’” Michael Palin says as he discusses the origins of his new book, Erebus. It’s a recognition that’s well earned. The former member of Monty Python has hosted nine travel documentaries so far (ten if you include the segment he did in Great Railway Journeys of the World) and published an accompanying book for each adventure, traveling to the South Pole, the Sahara, and North Korea.

His latest adventure is a little less straightforward.

In 1845, the HMS Erebus, accompanied by the HMS Terror, sailed into the Arctic on an expedition to discover the Northwest Passage—and seemed to vanish into thin air, making it one of the biggest disasters in British naval history. Erebus serves as a sort of biography, covering the ship’s entire lifespan, beginning with its construction as a bomb vessel, giving a voice to Palin’s fascination with the topic.

I sat down with Palin to talk about the ship, the importance of addressing a historical event while taking a modern perspective into account, and his interest in disasters and mysteries.

This interview has been edited and condensed.

You started in comedy—I think the pivot to travel documentarian is not something that people would necessarily expect. How did you get started doing travel documentaries?

Michael Palin: I always liked the idea of travel and finding out about places so different and new and unusual. I grew up in the north of England. We didn’t go anywhere, so when I got the opportunity, I would try and travel. I did a documentary about a train journey right through England; the BBC saw that, and they came up with the idea of Around the World in 80 Days, which was the first big travel series I did. I learned a lot on that trip. I learned how best to relate to people, and what I was really interested in was how people live, and meeting people on the street rather than talking to lots of politicians or leaders of industry and all that. It worked, and then the BBC said, “Yeah, okay, anything else you want to do?” And so the geographer in me came out. I said, “I’d love to go to the North Pole and the South Pole,” and that’s where the second one came out, Pole to Pole. It’s all kind of melded together in some way. There are connections—a love of travel, a curiosity about the world—which is really at the heart of Erebus. That’s why I related to the journey, because they’d been such extraordinary places, utterly remote places, and then-unknown places. Nobody knew what they were going to find. That was an extension of what I was hoping I was doing when I was traveling.

How did you decide on the scope of what your book would encompass?

The first thing I read about Erebus was about her first journey to the Antarctic, and that struck me as a most extraordinary, epic adventure. These men went south over a period of four years and saw things no one had seen before; they confirmed that the Antarctic was a continent, which no one had known before. I knew a little bit more about the lost expedition, but as I read more about it, I realized that these two journeys were very interesting dramatically. One was a serious attempt to use peacetime Navy for scientific discovery. The second was a little bit of national glory. “We now have the men, we have the ships, we have the knowledge, boom. We’re going to go through the Northwest Passage, where no one has been before.” As soon as the Northwest Passage was being discussed, there were people saying, “You can’t do this, you shouldn’t be doing it. You haven’t got the right ships, it’s not the right time of year.” Of course, it went spectacularly wrong. I always envisioned it as telling a story. I wanted to make sure it’s as dramatic to a reader as it was to me in my imagination. What was at stake, what the people went through, what they actually endured, what they saw—all that should be melded into a narrative. That’s why I decided to make it a story of a ship rather than being about individuals. It was the Erebus, the ship itself, that carried it through. The men didn’t survive. The ship did.

A big part of the book is your own journey following in the expedition’s footsteps. How did that all come together?

When I was thinking of how to write the book and what I could put into it that would be my own voice rather than just reciting lots of facts, I thought, “One thing is that I can travel to some of these places that were important for the expedition.” I thought that was important, because I would get not only some idea of what they were up against, what they saw, but also I would be traveling, myself, in their footsteps, as it were. What I really wanted to do was to get to the wreck site, put on the scuba outfit, go down there, and fondle the ship. That didn’t work out, for very obvious reasons, but I did go up to the Northwest Passage. I wanted to get as close to where they’d been as possible.

Have you spoken to the researchers about maybe diving in the future?

Yes, I have! I met a guy who’s been in many expeditions up there, and he said there’s an expedition next year and he could put my name forward. I think, diving, you probably wouldn’t be allowed to do, because I’m clumsy, and I’d probably put my foot through a light or some piece of history. They only have a short time they can actually do the exploration. This year, they had one and a half days that were ice-free. How frustrating is that? What can you find in a day and a half? You’ve got to wait until next summer and hope you have a good season. It’s still very difficult up there.

Something I was struck by was that you work in a lot of more modern concerns; you talk about imperialism and colonialism and the effect they had on the places these men went. Was giving that context something you always had in mind?

It just came about from reading the accounts and finding that these were men of science, products of the Enlightenment, and yet they still shot everything on sight—birds, and all that sort of thing—and trying to square that with the world now. I realized that part of the whole underlying spirit of the expedition was to civilize the uncivilized world. They didn't want anywhere in the world to be uncivilized. It had that tragic and awful manifestation, where the aboriginals, for example, in Van Diemen’s Land, were just hunted out. They were considered savages. And why did they take livestock on board the ship? They wanted to stop at islands and take the sheep and the cattle off so that they could multiply, and people could go and live on the island. That would be another wild island that had been civilized by the expedition. That’s why I think they were looking for the unknown. They didn’t like somewhere to be a blank on the map.

There’s been such a sustained interest despite the fact that everything happened such a long time ago. Do you have any theories as to why this event has had such longevity in the cultural fascination?

I think it’s partly because of the scale of the tragedy. It wasn’t just a few people getting lost in the ice, it was two very well-equipped ships and their entire crews. They just disappeared. It’s a bit like the mystery of whether the two climbers, Mallory and Irvine, got to the top of Everest in 1924. One of them was discovered near the summit. What happened to the other one? Did they get to the top? Were they the first people there? Mysteries like that can fascinate people.

How was the experience of writing Erebus in relation to your other books?

To write a book like this and sustain it, you’ve got to have self-belief, and that, I’ve found difficult. You come to think, “I’m writing this as my own particular fascination, who on earth is going to be interested?” People expect something different from me as a traveler or comedian. There’s not much of that in this book. I thought, “If I really think it’s interesting and exciting, then I’ve got to keep going.” I never actually at any point had writer’s block and said, “I don’t know where this is going.”

I take it you don’t have any immediate plans for a follow-up book in this historical vein?

I don’t. I’ve always had a bit of a butterfly mind. Things come up out of the blue and interest me. Films, artists, comedy—it just depends on what comes along. I think this will stand alone. I don’t think I’m going to do a series of naval stories. But who knows? Everything I do, I do it for an audience. That’s why you write. So you’ve got to find out what the audience like about it, or what they don’t like about it, and that gives you a clue as to what to do next. At the moment, I’m just deeply involved in telling people about it, that’s taking up plenty of time. But sometimes, when you’re traveling, that’s when the ideas come.

Sign up for our newsletter to get the best of VICE delivered to your inbox daily.

Follow Karen Han on Twitter.