Billionaires Are Raging and the Minimum Wage Is on the Ballot

November 6, 2018It's never been a bad time to be a billionaire in America, but the .01 percent are having a particularly good year.

If you're part of that vaunted club, your tax bill this year will likely be smaller than usual thanks to Republicans in Congress passing a massive tax cut targeted to disproportionately benefit the rich. And even as Democrats seem poised to win the House in Tuesday's midterms, Donald Trump's presence in the oval office means billionaires are safe from serious taxation or scrutiny of any kind for the foreseeable future.

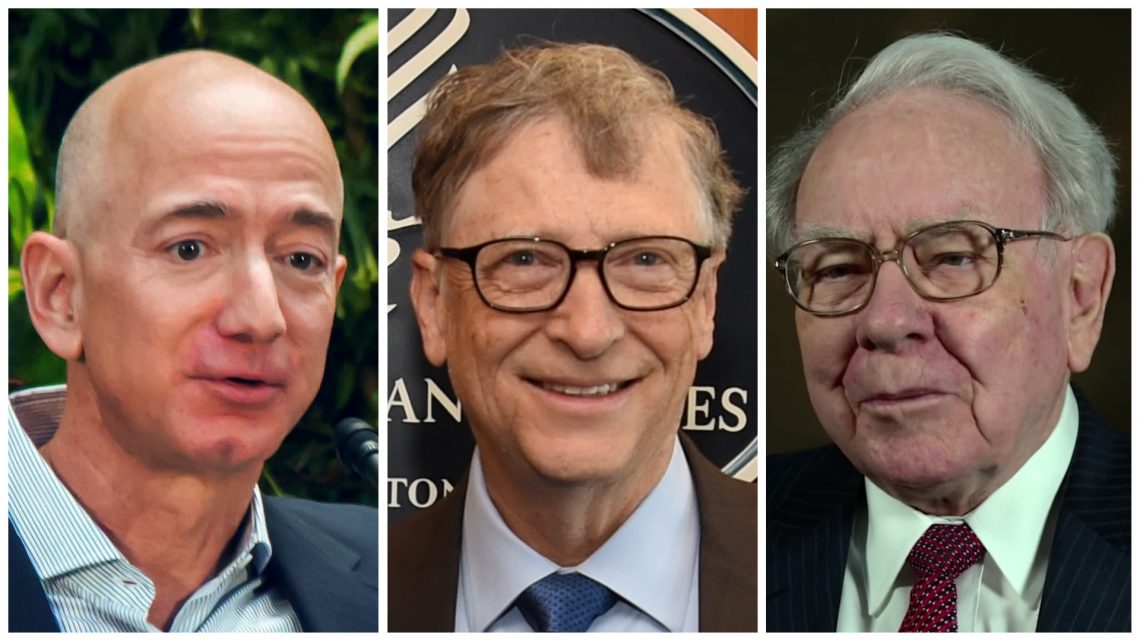

In fact, according to a report released last month by Swiss bank UBS, 2017 was the best year worldwide for billionaires ever, with their total wealth increasing by $1.4 trillion to nearly $9 trillion total. (Among other things, the report attributed the spike to China "minting 2 billionaires a week.") Another report released last week by the Institute for Policy Studies went further, showing how just three mega-rich families in the US—the Waltons of Walmart fame, the Kochs (the conservative mega-donors and energy mavens), and the Mars family (candy moguls)—have enjoyed a nearly 6,000 percent increase in wealth since 1982. According to that same report, three people—Jeff Bezos, Bill Gates, and Warren Buffett—owned as much wealth as the bottom half of Americans combined.

You don't need those specific statistics to know that inequality is in on the rise in America, but they underscore how bad the problem has gotten. The good news is that normal people are mad as hell about this, and they're doing something about it.

Voters in Missouri and Arkansas on Tuesday will vote on whether to (slowly) raise their states' minimum wages to $12 and $11, respectively, following the example set by states like New York and California and cities from Seattle to Chicago. The activists and advocates behind the two referendums—both in states Trump won handily in 2016—were confident in the final stretch of the campaign that even as the president doubled down on racism, working people were going to look out for themselves.

In other words, just because the national conversation has hinged on identity, hate, and terrorism of late—largely thanks to the messaging of Donald Trump and his Republican Party—doesn't mean there's no time left to go after entrenched oligarchy.

"There are people in Washington who are bragging about this economy, but I think these initiatives make clear that voters aren't satisfied," Jonathan Schleifer, executive director of the pro-minimum wage hike policy and advocacy group the Fairness Project, said on a conference call with reporters last week. "Real wages for working families haven't budged in decades."

David Cooper, senior analyst at the left-leaning Economic Policy Institute, echoed him. "The central challenge facing working families in America today is stagnant pay," he said on the same call.

That income inequality has exploded, with the rich taking home an ever-larger share of the economic pie and working and middle class people struggling just to get by, is an old story. But somehow the data points and brutal tales of deprivation continue to shock. Last week Third Way, a centrist policy shop that has traditionally pushed Democrats to embrace free markets, released its own analysis of major metropolitan areas and the economic conditions therein. It was not pretty:

Nationwide, just 38 percent of jobs pay enough to afford a middle or upper class life for a dual income-earning family with children; 32 percent of jobs pay a living-wage; and 30 percent pay what we call a “hardship” wage, which is less than what a single adult living on his or her own needs for basic necessities.

Trump has been crowing about a lengthy stretch of decent-to-robust job creation (partly) on his watch, and it is true that unemployment in October remained at a historic low. But many people are still struggling with student loans, credit card bills, auto loans, and other forms of debt—consumer debt is estimated to hit $4 trillion by the end of the year. Low wages, fueled in part by a federal minimum wage of $7.25 an hour, are harming people's chances of breaking out of that cycle.

"Costs keep going up, but my wages haven't kept pace," Azoria Morales, a 28-year-old single mom who works full-time in house-keeping in St. Louis for $8.50 an hour, said on the call with reporters last week. "It's not something I like to talk about, but I can hardly ever afford to pay my bills in full. I pay just enough to keep the lights on."

As Cooper, the policy analyst, argued, it didn't have to be this way. Republicans have largely been dead-set against raising the federal minimum wage since George W. Bush and Democrats agreed on the last increase back in 2007. (In 2014, Republicans in Congress scuttled an attempt by Barack Obama to increase it again.) In the years since, unions continued to lose strength in the face of withering attacks from the right, further reducing pressure on bosses to pay workers a fair wage.

But in Missouri, despite statewide support for Trump, voters this August rejected a measure passed by Republican lawmakers that would have let people opt out of paying union dues, sapping organized labor of its muscle. And US Senator Claire McCaskill, the moderate Democrat who's won two terms in the state even as its voters have drifted right, was looking like a decent bet to win another six years in Congress on Tuesday. Her voters are likely the same set—along with some of the ones backing her Republican opponent—who rejected the anti-union law and might like the idea of paying workers more.

The broader political environment in Arkansas, on the other hand, might not be as favorable to a pro-worker ballot measure. But voters there did raise the minimum wage four years ago, even as Republicans dominated statewide elections, and one local survey found support cracking 60 percent. Advocates of the bump knew they had basic logic on their side, if not partisan loyalty.

"Nobody working full time should have to live in poverty or need food stamps just to feed themselves," Amy Wilson, a school custodian in Russellville, Arkansas, said on the conference call. "I know we can do better than that."

Sign up for our newsletter to get the best of VICE delivered to your inbox daily.

Follow Matt Taylor on Twitter.