Whitey Bulger’s Real Life Was Crazier Than the Movies

October 30, 2018It only took 89 years for someone to get to Whitey Bulger.

The notorious Boston gangster defined by a decades-long identity crisis—he was an FBI informant and also one of the most notorious and feared crime lords in American history—was murdered Tuesday at a high-security prison in West Virginia. For reasons that were initially unclear (let the speculation begin), he had been transferred from a facility in Florida to the US Penitentiary at Hazelton. Within hours of arriving, he was dead.

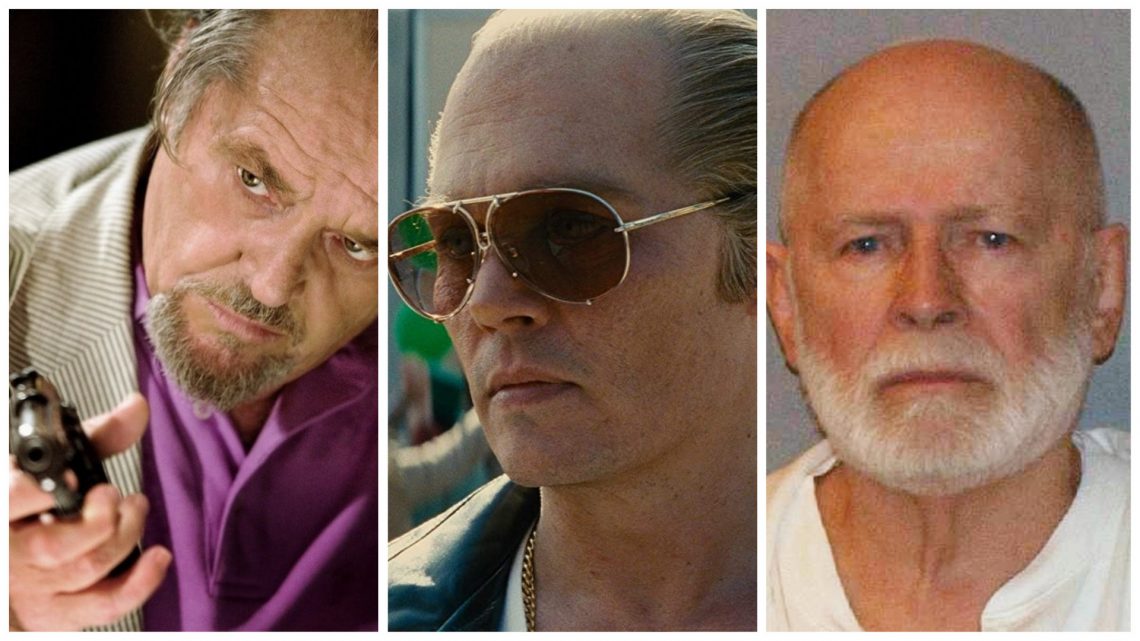

James Joseph Bulger Jr.'s killing brought to an end one of the more sordid chapters in his city's history. His tale was one of rags to brutally acquired riches: An Irish American born in South Boston in 1929, Bulger took to the post-Depression streets early, in his teens earning a reputation as a fist-fighting thief stereotypical of his hometown. He had an intense, parochial loyalty to his native turf that would eventually lead to the higher rungs of the American gangster ladder. (His stature in Boston's cultural imagination of fetishized masculinity is outshone perhaps solely by Ralph Waldo Emerson, the Kennedys, or, less gloriously, Mark Wahlberg.) Decades later, he was portrayed by Johnny Depp in the biographical crime drama Black Mass after Jack Nicholson famously played a version of somebody very much like him in The Departed, his near psychotic bouts of unhinged brutishness maybe just slightly fictionalized.

The only thing more legendary than the severity of Bulger's violence was the man's quickness to resort to it, and his ability to rationalize—and sometimes bury it—beneath his "good deeds." He was often described as a Robin Hood figure who literally handed out turkeys to his neighbors on Thanksgiving and helped old ladies across the street. But he was also known to extort drug dealers; in the 1980s, he trafficked weapons to the IRA. He was called ''evil" by some of his former partners, and according to the New York Times, he may have been moved from the Florida prison to the one in which he was killed after threatening a staff member.

Bulger was a ready-made caricature of this nation's prototypical gangbanger—a bookie, a loanshark, a protect-the-business-by-any-means-necessary kind of guy—and he had an origin story seemingly prewritten for a true wise guy, or at least for a Martin Scorcese flick. Bulger developed his ruthlessness young. According to his Times obituary, "tales of his exploits were learned from childhood there: how he shot men between the eyes, stabbed rivals in the heart with ice picks, strangled women who might betray him and buried victims in secret graveyards after yanking their teeth to thwart identification." His family raised him in a Catholic household; his father worked as a longshoreman; and he was the second of six children. (Adding to his lore, his brother, William, was once president of the University of Massachusetts and eventually served for 18 years as president of the Massachusetts Senate. The latter famously refused to turn on his criminal kin.)

Bulger's reputation would have caused fictional gangsters to blush, his tour of criminal hotspots the stuff of deranged fantasy. In the 50s, Bulger robbed banks along the East Coast and in Indiana and spent around ten years in jail for it. (Some of them in Atlanta, where he claimed he was a guinea pig for Ken Kesey–esque CIA drug experiments, and a few in Alcatraz.) Throughout the 70s, Bulger firmly solidified himself as an old-school mobster with manic flair. After his spree jacking cash from tellers, Bulger and an associate, Stephen Flemmi, became leaders of the Winter Hill Gang, a staple of the Boston-area Irish mob. But as the Times reported, this was around the same time—at the behest of his childhood friend turned FBI agent, John Connolly—that the duo became informants against the Mafia's Patriarca family.

It was a somewhat confusing and treacherous web that, in short, permitted Bulger a degree of immunity while he went around committing or ordering heinous hits. (He was said to have had many people shot in the head.) When, in 1994, Connolly learned that Bulger would soon be indicted on federal racketeering charges, he tipped his longtime pal off. (Connolly himself would later be put behind bars for second-degree murder, after helping Bulger in arranging the killing of a gambling executive in Miami who they feared might flip.) Bulger fled—and was on the lam for 16-plus years, topping the FBI's Most Wanted List along with Osama bin Laden.

In 2011, police caught up, arresting Bulger, along with his girlfriend, Catherine Greig, without incident in Santa Monica, California. Then, in 2013, in a highly publicized trial in which the families of his victims watched in terrified satisfaction, his former protégé, Kevin Weeks, testified against him, and a silent Bulger was found guilty of 11 of the 19 murders he was charged with (along with a host of money laundering, racketeering, and other charges) and handed a life sentence. The whole escapade was, naturally, turned into a documentary. He was denied any possibility of parole.

As details emerged about Bulger's killing, it seemed likely just a matter of time before the scene hit the big screen. Such a gruesome and fantastical demise couldn't be made up.

Sign up for our newsletter to get the best of VICE delivered to your inbox daily.

Follow Alex Norcia on Twitter.