What Happens When Your Dad Raises Your Whole Family to Be Criminals

October 9, 2018One Christmas when he was still a small child, Bobby Bogle’s father, Rooster, gave him a heavy metal wrench wrapped in a brown paper bag as a present. Confused, four-year-old Bobby didn’t know what to make of the gift—until he recalled his father telling what amounted to war stories about the time he served in Texas prisons for burglary. Bobby decided the wrench was a tool of the family trade, and snuck out early one morning to do a smash and grab at the local market. After he scurried home with a bunch of "hot"—stolen—Coca-Cola bottles in his hands, his father greeted him like he'd just hit a home run in a Little League game.

For the Bogles, crime really did run in the family.

For his new project, Pulitzer Prize-winning New York Times journalist Fox Butterfield had set out to find a family that was uniquely familiar with the criminal justice system. But he stumbled upon something more: A clan with six members currently in Oregon state prisons and a total of some 60 people who’d been in jail or prison or else been on probation or parole dating back to the 1920s. In the resulting book, In My Father's House: A New View of How Crime Runs in the Family, Butterfield tracked down various members of the Bogles in prison and out, persuading them to tell their stories while probing at the factors that contributed to their disproportionate run-ins with the law. VICE talked to him to find out what it all means in time of resurgent "law-and-order" politics.

VICE: Why focus on the role of family in crime given the abundance of research showing environmental factors like poverty are so central to this stuff?

Fox Butterfield: [What] really caught my interest were the studies that had been done around the United States and in London looking at how crime tends to run in families. We tend not to write about white crime in the US anymore—it's so heavily concentrated on blacks. I wanted to find a white family to try to take race out of the equation. Although these studies have existed for a number of years, nobody ever really did anything with the research. Nobody went to look and see why the family behaves in that fashion.

Why do you think studies on how family might factor in crime are not better known?

When I talked to some criminologists about it, their feeling was that a lot of American criminologists are almost afraid to focus on the family as a cause of crime because, until very recently, you would have been accused of being a racist if you suggested that there was a family connection or a biological or genetic connection to crime. A lot of the criminologists went looking in all these other directions. They went looking at bad neighborhoods, poverty, gangs, and drugs. The family was ignored even though these studies were out there. When I saw how extensive the studies were, I just jumped at the opportunity.

So was your aim with the book more criminology exposition or Bogle family history?

It's trying to be a blend of both. The intellectual foundation or background for the book are all the studies which have the statistics showing how crime runs in families. That's the framework for the book, but then the flesh and the blood for the book are the stories of the Bogles themselves. I hope that it's a successful way of blending the two things together.

Given the dangers of sort of dooming people by virtue of their origin, what real-world conclusions do you think are valuable about a family like the Bogles, besides the sheer number of them who broke the law?

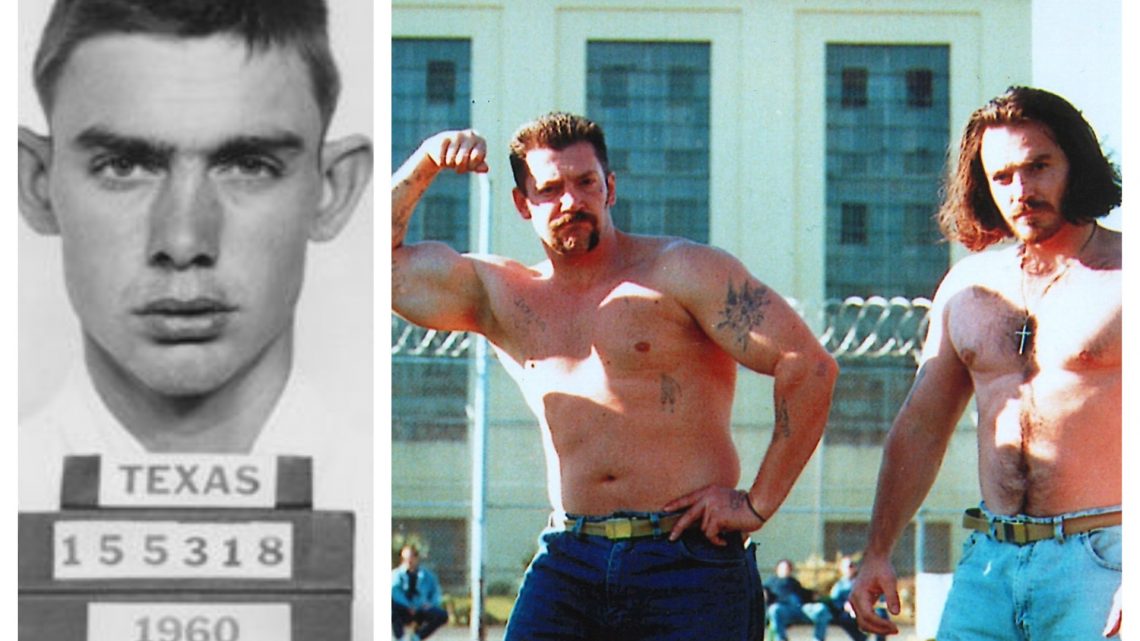

In talking to the members of the Bogle family, they all told me right from the get-go that when they were very young, their father and their mother and sometimes their aunts and uncles, older members of the family, would take them out and commit crimes with them. They were learning to commit crime as part of the family activity. It's what they did. Rooster Bogle would take his sons out once a week or so to visit a prison near Salem, Oregon where they lived, a great, big prison on the outskirts of the city, and point to the prison and say, "Look carefully, boys, because when you grow up, this is where you're going to live."

They didn't take that as a warning. They took that as a dare, and they figured that was what they were supposed to do.

They came to look on being criminal as something honorable for their family. Criminologists like to call that the social-learning theory. It’s a process of imitation. Looking a little bit deeper, I saw what criminologists refer to as social control, which means they didn’t have a lot of strong attachments. They didn't have any social bonds. They didn't have attachments to teachers and weren't in the Boy Scouts. They didn't play on a Little League team. They didn't go to church or Sunday School or anything like that. They didn't belong to any other social groups and lacked other role models for activity except for their family. Their only bonds were to members of their own family, who were already becoming criminals.

How did you steer clear of dangerous conclusions about genetics and crime?

I began to get interested in the role that genetics might play in this because, since the decoding of the human genome, it's now possible for criminologists to start talking about the possible role of genetics in crime. That was really impossible to do until quite recently, because if you suggested that biology or genes had some role in crime, you would have been labeled a racist or a Nazi. But there are now criminologists who are actually working on this and discovering some genes that, in combination with a family environment like the Bogles', can predispose you towards certain type of behavior.

Of course, the interesting one is the gene which can make people more impulsive, which doesn't necessarily make them criminal, but it's often a precursor to criminal activity. I explored that, but I'm not a geneticist. I'm not a scientist, so I can't take that very far. There is interesting work that is starting to be done now on the role of genetics, but the people who are doing the work are very careful to say that there's no such thing as a crime gene. There are thousands of these genes and it's the combination of certain genes with a family environment like that of the Bogles—you need to have them both, the environment and the gene.

Don't you worry your ideas about crime running in the family might be viewed or interpreted in a troublesome way in this moment of Donald Trump-style anti-crime politics?

Well, I've given up trying to predict what Trump could do. I'm hoping the book is able to stand on its own and doesn't get caught in a debate between the right and the left or the Trump and the anti-Trump people. I'm not trying to suggest that certain families are cursed by their innate inheritance and will never be able to change, because I see that some people do change. But I think we could have a much more efficient criminal justice system if we were more aware of how crime does run in families. We could try to work with the people when they're members of those families while they're young. The earlier you can get people to change their behavior, the easier is it. After a while, it kind of gets baked in.

I was in prison and know a bit about what people might call the convict or criminal mentality. But how do you think that mentality survived in a family-unit like the Bogles' over multiple generations?

That kind of mentality that you're talking about got set in their family. They were keeping some of those things, those traditions and that mental outlook. They took pride in [that mentality]. Rooster gave these little tattoos to his kids. They're really dots on the left cheek, right under the left eye of each of his children. He told them that it was a gypsy mark, but actually it was a mark convicts had used in federal state prisons back in the 50s and 60s. I don't think it's carried on, but at that time it was quite widespread.

It seems like it wasn't just a matter of survival, but almost pride—and actively rejecting the values of society.

Somehow it becomes a part of the family identity. It's what they believe in. The Bogles were also very clannish. They hang out with themselves, they didn't have a lot of other friends and they didn't allow their kids to play with other kids from other families. They just played with their own relatives, and that was another factor in their story. They didn't want other people to know what their lives were like, and so they all let the kids grow up where the family knew what their parents or their aunts and uncles, and grandfathers and grandmothers were like and they didn't know much about other folks. So being cut off from the rest of society was a factor.

With some distance from the subject, do you think this story is more about poverty or lack of opportunity, or this unique worldview that was handed down? Is that an impossible choice?

I've wrestled with that one. The Bogles are a disadvantaged white family. They don't have the problem that African Americans face of having dark skin and having people prejudiced against them. But they have this way of seeing the world where they think what they do best is commit crimes, and they get honor by committing crimes. For them, it's a cultural thing.

Not to belabor the point, but how do you avoid stigmatizing people with work like this, or pushing the idea that they're doomed by their blood or something?

I point to several people who were able to break free of this. Tammie Bogle is a deeply religious person. Even though many of her brothers and a couple of her own kids got in trouble and ended up in prison, her strength and her relationship with religion has helped guide her along a very good path. Ashley Bogle, although she was surrounded by people who were committing crimes, decided early on that she didn't want that. That wasn't for her and she focused on her studies at school. I don't believe people are preordained to go this route. They're making choices along the way. I wouldn't say that everybody in the family's going to turn out as a criminal. There are paths out of it.

Learn more about Butterfield's book, which drops October 10, here.