That Was Then, This Is Too

October 4, 2018A New York Times editorial noted that the accuser “made clear that she had raised her complaint reluctantly” and “her demeanor impressed friend and foe of the nomination alike.”

Sen. Orrin Hatch said that she was impressive, but “the facts do not line up.” The Judiciary Committee chairman said there was no reason to postpone the confirmation vote.

Some version of all of these things occurred last week, in 2018, after Dr. Christine Blasey Ford testified about the assault she remembers experiencing as a teenager at the hands of Supreme Court nominee Brett Kavanaugh.

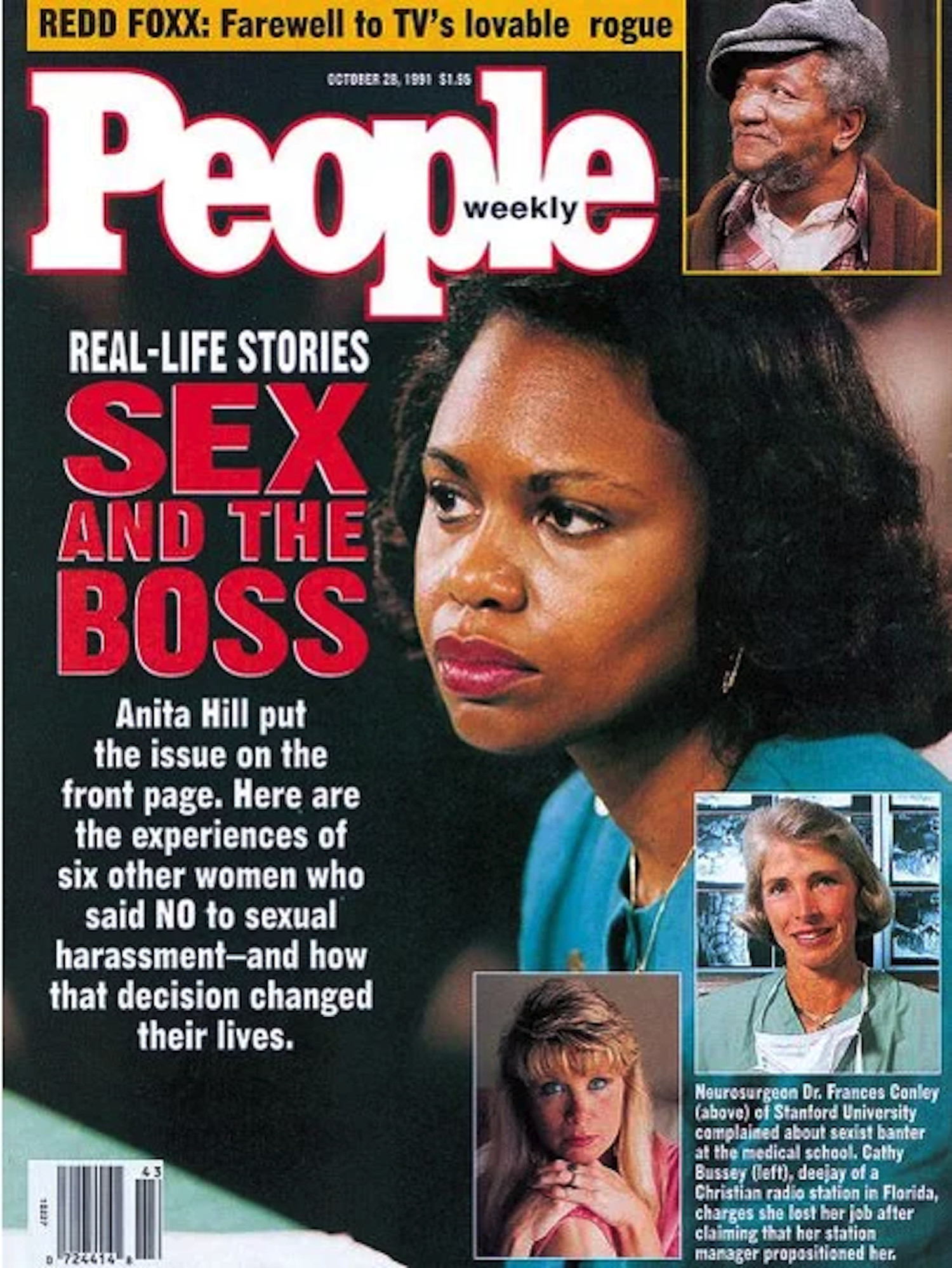

They also happened in the first week of October in 1991, when Anita Hill told the nation that she experienced sexual harassment while working for the Supreme Court nominee in question at that time, Clarence Thomas.

In the 1991 Times editorial, the paper’s board wrote about the explanations Hill provided for why she continued to work for Thomas after the behavior she described. “Senators who find her behavior discrediting have something to learn about the realities of sexual harassment,” they wrote.

It’s unclear if all, most, or some of those who discredited Hill based on that behavior gleaned much about the realities of sexual harassment, but 27 years later, many seem to have a lot to learn about the realities of sexual assault, and shame. Diving through the responses then and now provokes an unsettling feeling; regardless of whether you experienced the hearings first-hand, it’s fair to wonder whether anything has changed. Those who lived through both Hill and Blasey Ford’s testimonies in particularwould be forgiven for feeling that time is a flat circle.

A day after that Times editorial was published, the Tuscaloosa News declared that whether or not Clarence Thomas was confirmed to the Supreme Court, American women had already gained a victory.

When the public learned that despite Hill’s allegations, the Senate Judiciary committee was intent on proceeding with a vote without further investigation, women “flooded senators’ offices with telephone calls, they cranked up their fax machines, and women members of the House even staged an unheard-of revolt.”

“In a rare show of female power Tuesday, they convinced the U.S. Senate, with 98 of its 100 members men, to delay Thomas’s confirmation vote long enough to examine the charge that he sexually harassed a former assistant,” the report read.

That “unheard-of revolt” played out in a way that would shock young women today. There’s an iconic photo of Barbara Boxer leading her some of her House colleagues up the steps of the building, but little discussion of what happened when they arrived at the room where the all-male Senate Democrats were strategizing in the upper chamber. The men wouldn’t even let the women enter the room, the literal manifestation of a boys’ club.

At the time, Rep. Patricia Schroeder (D-Colo.), one of the seven women who tried to storm the room, told reporters, “America’s women want to see the Senate doing something for them, rather than to them.”

Republicans have lashed out at Dianne Feinstein for not sharing the letter from Blasey Ford sooner. Feinstein insists that she was respecting Blasey Ford’s request for confidentiality. Back in 1991, Joe Biden—whose office received Hill’s allegations—said the same: Hill had asked that her name be kept secret, so how could they investigate her harassment charges?

Republicans are wringing their hands, warning that if attempting sexual assault as a teenager (and in college, and possibly later) is a dealbreaker for those interested in government work, we won’t have anyone willing to take on such jobs. Back in 1991, Thomas’s most vigorous supporter, Sen. John Danforth, a Republican from Missouri, warned that hearing Hill’s complaints in public “would invite a host of false charges against the nominee,” the Tuscaloosa News reported.

(In fact, other women did come forward with allegations and testimony to corroborate Hill’s account, but the Democrats struck a deal with their Republican colleagues and did not allow any of them to testify.)

Meanwhile, the women outside the Senate chambers were worried about what Hill was about to endure. “She will be forever branded,” one woman told a reporter. “Nobody does that lightly.”

Before the public outcry invoked by Hill’s position brought women in droves to the Senate chamber, Republicans had been assured of a majority in favor of confirming Thomas, which is why they resisted a delay—much like their circumstances with Kavanaugh, before Blasey Ford’s testimony brought women out even more than they already had been, their bodily autonomy threatened by his assumed politics.

In 1991, the protests postponed the vote and forced the Senate to listen to Hill’s testimony on live television, in front of all of their voters. Last week, Sen. Jeff Flake was confronted by two women who stood in the doorway of the elevator he was in and pleaded with him to take their experiences of sexual assault seriously, and not vote to confirm as he said he would. As in 1991, the presence of women showing up as concerned citizens changed the game: The FBI would now investigate the accusations against Kavanaugh.

We know what happened on television in 1991: Hill was subjected to humiliating questions from a panel of white men. Biden suppressed witnesses who could have supported her testimony; Thomas was confirmed by a narrow margin.

But the YouTube clips of the hearing don’t convey what it felt like then; what it was like to witness and live through this incredibly public reckoning.

One man who worked as a lawyer on the Hill while the Clarence Thomas hearings were ongoing says that the people he remembers most are the ones who were his age: the aides of the Senators in the spotlight, though perhaps that’s because he himself was a young person at the time. (Citing concerns over professional ramifications, he asked not to be identified, but agreed to share his memories of that time.) “Nobody who was an aide wanted to be there,” he said. “Unlike this debacle, the Anita Hill thing caught everybody by surprise. No one had any idea this was coming.”

He remembers watching the aides sitting behind their Senator bosses on national television. “While the old guys were making asses of themselves, you saw us cringing and thinking, ‘My god, I’m on national TV.’ No one wants to be on national TV while they’re doing this.” The senators, at least, were used to being in the spotlight. “Unlike the senators, the aides are never on national TV.”

He said the HBO film about the hearing—Confirmation—“gets the politics right,” but gives an inaccurate portrait of that time in one crucial way. “I looked at the aides there and I thought, ‘There are a lot more women than I remember on the Hill.’”

There still aren’t an equal number, of course, but back then there were so few, nobody seemed to bat an eye when Joe Biden explicitly said, while gently questioning Thomas, that he would treat his male staffers different than his female ones. “That was the culture there,” the lawyer told me. It was understood that you “say different things to men than women.”

One experience that has stuck with him was what happened after a political figure rudely dismissed some of his work. Erwin Griswold—the dean of Harvard Law School who famously asked each female student why they were taking the place of a man—confronted the politician and told him, “The young man is right,” the lawyer says.

“I got my apology in the men’s room while we were both taking a piss,” the lawyer shared, before explaining he wondered where Griswold would have apologized to him if circumstances had been different. “I kept thinking to myself, ‘What if I was female?”

More than 20 million households were glued to their televisions when Hill testified. (The only televised congressional event with more viewers was Oliver North’s Iran-Contra testimony in 1987, which drew about twice as many.)

Lisa Palac was in her late 20s when Hill’s testimony aired. She’s now a therapist in Los Angeles who specializes in sexual issues and drug trials; she describes herself at the time of the Thomas confirmation hearings as “a young, radical feminist.”

“It was the first time that anyone had ever come forward in that way with these reports of sexual harassment at, I felt, such a corporate level,” she said. “I thought, ‘Wow, this is really going to change the world and things are really going to be different.”

Palac still remembers the incredulity she felt watching Hill’s testimony, thinking, “I can’t believe the way they’re treating this woman, I can’t believe the way they’re talking to her, I can’t believe they’re treating this like this a trial.” She thought they couldn’t possibly confirm this man to the Supreme Court. She thought he couldn’t possibly use his race to fend off accusations from a black woman.

Like many women at the time, Palac recognized the experiences Hill described. She’d experienced men talk to her that way, treat her that way, sexualize her in that way, even in contexts that were wholly unsexual. Until she watched Hill testify, she had “sort of chalked [those experiences] up to—that’s just part of being a woman, that’s just what happens when you’re female.”

“Are we seriously here again? Nothing seems to have changed.”

I was struck by Palac’s experience because it seemed to so acutely mirror my own, and those of other women my age with whom I’ve spoken, during the Ford testimony. Some of us found ourselves suddenly, uncontrollably sobbing as Ford spoke. We were remembering things we had long buried; we were seeing experiences we’d accepted as “just what happens when you’re female” in a new light. We were wondering what had conditioned us to accept those experiences, and then hearing pundits and government officials saying “boys will be boys” and wondering if “being boys” meant assaulting girls, what did it mean to be a girl? We had these conversations in public, on platforms that were more than a decade out from being created during the Thomas hearings, watching C-SPAN on our laptops, catching cable news—a fledgling idea in 1991, now a source of millions of views—in airports. While 20 million may have tuned in in 1991, at least that many watched this time around. The availability of the information is now spread wide enough that it must have made a difference in the discourse. Right?

Erin Bradley was a senior in UC Santa Barbara when Hill’s testimony was shown on a huge TV in the university center on campus. Now a 48-year-old tax attorney and mother of two in Burlingame, CA, Bradley remembers watching Hill amid a crowd of her peers, “not all day… but enough to realize this was pretty much a revolution taking place a lot of people my age were paying attention.”

Her memories center around Hill’s poise and her calm voice. “She never got emotional that I saw; she was never upset in either the questions she received or in her responses,” Bradley recalled. Thomas may have gotten confirmed, but Hill changed things for young women, Bradley says. The conversation about “what sexual harassment was and what did it mean”—and what sort of harm it inflicted on victims—was ongoing. One day, she found herself confronting her supervisor at the pub where she worked and telling him, “I think what you’re doing to me is sexual harassment. Knock it off."

“All of a sudden that was part of the vocabulary,” she told me. Just as she’d done for Palac, and undoubtedly countless other women, Hill had given Bradley the ability to articulate something that had been done to her. And the ability to name this thing was enabling women to protect themselves from it, and fight back when confronted with it, even if only sometimes, and in some small measure.

This was happening all over the country, and not just on college campuses. On Oct. 13, 1991, as the second day of the Hill-Thomas hearings was underway, women established a “speaker’s corner” in Union Square, invoking the site’s “historic role as a place for free speech and ideals.” Then-City Comptroller Elizabeth Holtzman highlighted the social and economic issues at play, asking "What would happen if it was a person who wasn't middle class and respectable? When will they ever be believed?"

That same day, the hearings were apparently on the minds and in the mouths of people on the streets of Chicago. A woman visiting the city with her teenage son told a New York Times reporter that the hearings prompted a conversation with her son about sexual harassment. “I told Lee about a couple of experiences I’ve had.” Her son admitted he’d “never really thought about it before.”

"But now it makes me think about how badly people treat girls and get away with it. You see that all the time in high school,” he said.

In a Nov. 17, 1991 article for the Times, the late Gwen Ifill reported on a multi-day conference of female legislators where Hill was invited to speak. One day, female legislators from California called a hearing where 29 witnesses spoke of their experiences with harassment. A former San Francisco police officer, Louette Columbano, said her male colleagues chased her, forced her to watch a prostitute perform oral sex on a male officer, and took turns spitting on the windshield of her car after she had the audacity to complain.

Columbano said she never expected to talk about these experiences again, assuming they’d remain buried in her awful memories of that time. She’d gotten so used to being told she wasn’t a credible witness to her own mistreatment. But Hill testifying to the Senate had made her, and the other witnesses who spoke that day, finally feel that their stories might not be dismissed.

The Dr. Ford hearing also prompted these conversations and disclosures. The most high-profile, to be sure, came from the two women who confronted Sen. Jeff Flake in an elevator and pleaded with him to rethink his planned vote to confirm Kavanaugh, sharing their own experiences of sexual assault and abuse, and begging him not to look away from them, a moment that spread quickly and the few people present. Another woman tried to tell Sen. Lindsey Graham of her experience; he responded, “You needed to go to the cops.”

These moments of public disclosure are painful and frustrating for many, but provide relief for others. Bradley, the California tax attorney, said the women who confronted Flake “gave me a sliver of hope.”

“I was so heartened… that alone was so uplifting — painful but uplifting,” she said. “I don’t know [if] that would have happened in 1991. Maybe it did and we just didn’t have people with cameras all around capturing it.”

Now the public doesn’t necessarily have to rely on media outlets or powerful politicians to decide what they ought to know. Thanks to various social media platforms, victims and their attorneys can get information to the public directly. But those same technological innovations also allowed the senators who mistreated Hill back in 1991 to use the same tactics of humiliation and rumor-spreading that they employed back then, but on a much larger scale.

Senate Republicans in 1991 famously sought to discredit Hill by painting her as “a little bit nutty and a little bit slutty.” They “presented an affidavit from a man who said Professor Hill had mistakenly believed he had a sexual interest in her and was prone to fantasy,” releasing to the public a wide array of wild claims that they made no effort to check or verify. Sen. Orrin Hatch suggested on Oct. 13, 1991 that she was working with “slick lawyers” to take down Thomas for political purposes.

When they feared that a second accuser, Angela Wright, would tank Thomas’s chances, they made sure she couldn’t testify on television (noting that they’ve done the same thing to Kavanaugh’s other accusers, the lawyer who worked on the Hill in 1991 told me, “I knew they would bury the second witness”), and spread a rumor that Wright had been fired by Thomas for calling someone a slur against gay people. The purported target later said Wright never uttered the word, but it was too late. “It’s bothersome that nobody on the committee even bothered to probe” the rumor, Wright said years later. “If they had probed just a little bit, they probably could have realized he wasn’t telling the truth, just asked him where did that happen and what did you say to her.”

The Times intimated that Wright might “present a more complex picture” than Hill, citing criticism from Senate Republicans that she was “a disgruntled former employee with an uneven work history whose testimony will not be viewed as credible.” Her “uneven work history” involves being dismissed as an aide for a North Carolina Democrat in 1978, and writing a resignation letter when she quit a position at the United States Agency for International Development in 1984 “in anger over what she felt was mistreatment by her superiors.”

This time, it appeared Senate Republicans weren’t going to pursue the same strategy. Whether because they’d learned a lesson or because Dr. Ford wasn’t a black woman, they seemed to be making some effort to at least seem respectful of her. Even President Trump responded with such self-control, his aides were reportedly shocked.

But that didn’t last long. This week, the SJC posted on their government website a humiliating letter from a former weatherman and failed politician claiming intimate knowledge of Kavanaugh’s third accuser, Julie Swetnick, and her sexual preferences and mental instability. Orrin Hatch (who, according to David Brock, had leaked selective parts of the FBI investigation into Hill in order to smear her) eagerly tweeted the link. The same day, Trump went on stage at a rally in Mississippi and spent several minutes mocking Dr. Ford and her testimony, doing impressions of her, and getting a raucous mob of people to roar with laughter at a woman who told the nation that the most powerful memory of her sexual assault was the laughter of the boys on top of her.

Barely a few hours later, Chuck Grassley released a second letter, this time from an anonymous man claiming to have dated Dr. Ford, undermining various parts of her story. Various media outlets ran with this letter, without any indication that they’d made any effort to figure out who wrote it and whether he ever really did date Dr. Ford. To many, it all appears to have been for nothing that can yet be seen.

Even for women who witnessed it happen the first time around, there’s a sense of shock and horror watching it play out the same way again. Palac, the California sex therapist, watched Blasey Ford’s testimony through “tears of rage for what she had endured as an adolescent.” It brought to mind the patients she’s treated, particularly young women, who struggle to even recognize traumas they’ve experienced. Blasey Ford already had to share that she first disclosed Kavanaugh’s alleged assault on her in couples therapy, undoubtedly telling millions of strangers more about her personal life and her marriage than any of us would want anyone to know.

Palac said that while it may have been embarrassing and humiliating for Blasey Ford and her family, it was “also so brave and so important, because it’s so common.” Many of her patients don’t remember the incident that traumatized them, at least not in the way we tend to think of memories. “They don’t have visual memories of what happened, but they have a body memory,” she said. “Their bodies remember what happened.” (Recall how Blasey Ford explained that hormones like norepinephrine, released during a traumatic experience, can tattoo certain parts of memories on our hippocampus, while the rest fade away.)

Bradley listened to Blasey Ford’s testimony as she drove to work. When she pulled into the parking lot and shut off her engine, she continued to hear the testimony, and realized there was a woman sitting in the parked car next to her, listening to Blasey Ford. Bradley walked into her office and saw one of her male colleagues watching it on his computer.

“It was everywhere,” she said.

In the days that followed, she kept thinking, “Are we seriously here again? Nothing seems to have changed.”

It’s hard to disagree with Bradley. News reports from the week of the Hill-Thomas hearings—almost exactly 27 years ago—are eerily similar to what we’re reading now.

On Oct. 13, 1991, Maureen Dowd wrote in the Times, “The Senators seemed stunned, almost mute, at the ferocity of Judge Clarence Thomas’s language.” A different article that same day described the televised hearings as “marked by Judge Thomas’s expressions of disgust.” A third article noted that Thomas “told the committee he had not listened or watched Ms. Hill testify.”

An opinion column in that issue asserted, “Senators bear their own guilt. But they, like the judge and the professor, are also victims—caught in the vortex of President Bush’s decision to elevate an under qualified Judge Thomas to the nation’s highest court, and thereby forge a decisive conservative majority.” A Week in Review column titled “Theater of Pain” speculated, “Watching the trial-by-television of the case of Prof. Anita Hill v. Judge Clarence Thomas, in which the imperatives of politics, society and governance collided head-on, it was hard to escape the gnawing feeling that some great injustice had been done. It was just not clear to whom the injustice was done—the Supreme Court nominee or the lawyer who accused him of sexual harassment—or to what extent the President of the United States, the constitutional process or the American people were also harmed.”

Support for Hill wasn’t unanimous, and many believed that we’d never know the truth about what had happened to her. On her way home from D.C., a woman shook her finger at Hill in the Dallas airport, saying, “Shame, shame,” and a group of businessmen hissed when she walked by. (Blasey Ford and her family have had to hire security and leave their home because of death threats.) Even now, despite all the compelling evidence revealed in the intervening years, people insist that Thomas was wrongly accused.

And some of the players haven’t changed either. Orrin Hatch attacked Anita Hill, both publicly and privately; we’ve watched him do it again with Christine Blasey Ford. We are experiencing the same concerns about victims of sexual assault that women in 1991 had about victims of sexual harassment. The mediums we’ve debated on are more varied than ever, the discussion perhaps heightened because of them but still the same. What is that saying? That change is cyclical, that progress is followed by a step back, only to move forward again? Is this the lull before the big step? Things seems to have shifted for women, but maybe only for them, siloed still from men. And if it’s only changing for some, how much can it really?

In her first press conference upon returning to Oklahoma, a calm, steady Anita Hill acknowledged that she “had more to gain by staying silent,” but that she didn’t regret not doing so.

“I was raised to do what is right and can now explain to my students first hand that despite the high costs which may be involved, it is worth having the truth emerge,” she said, words that were echoed decades later by Blasey Ford, who described her own testimony as her "civic duty."

Hill continued: “I am hopeful that others who have suffered sexual harassment will not become discouraged by my experience, but instead will find the strength to speak up about this serious problem.”

They did, and such strength has been attributed to Hill. There were 6,127 case of sexual harassment in 1991, when Hill testified. Congress enacted new laws less than two months after Hill testified, and that number grew to 15,342 by 1996. Monetary awards to victims under federal laws rose from $7.7 million to $27.8 million.

But we know that sexual harassment, and worse, persisted. It remained terrifying to challenge certain powerful men, after Thomas was confirmed. When this most recent swell of the movement took hold, those who experienced sexual harassment and assault, those who acknowledged their experiences, tried to live up to Hill’s expectation. We don't know if the rest are ready for it, or if they ever will be. We know that much is sacrificed as progress rolls out, and its results are often incomprehensible. Even when it is laid out clearly, our history can be of little comfort. We can see only a sliver of life but feel all of its weight regardless.

Sign up for our newsletter to get the best of VICE delivered to your inbox daily.

Follow Danielle Tcholakian on Twitter.