What It’s Like to Be an Asian Adoptee in a White Family and Town

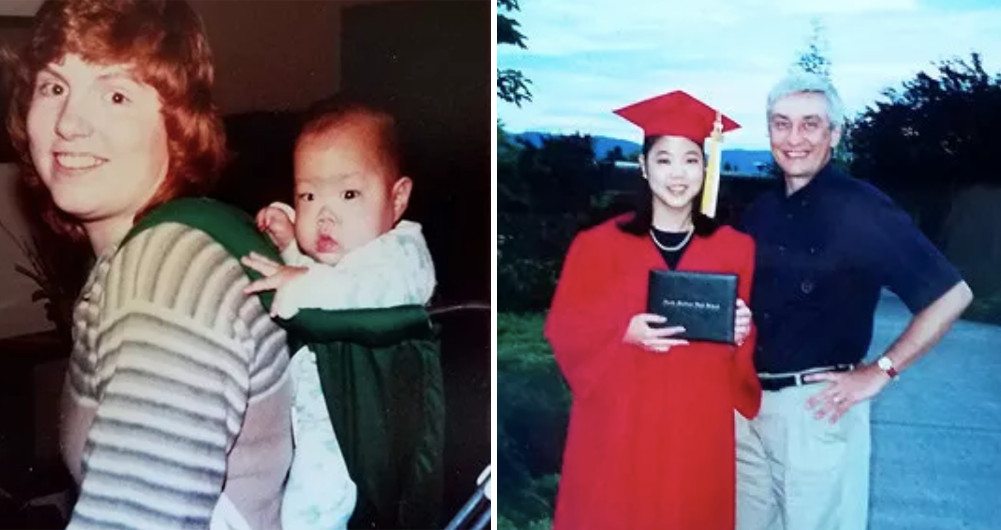

October 2, 2018Though transracial adoption is extremely common in the United States, the adoption narrative is rarely told from the point of view of the adoptee. Nicole Chung, editor-in-chief of Catapult and essayist for The New York Times, GQ, and Hazlitt (among others) sought to change this by penning her own transracial adoption story. In her memoir, All You Can Ever Know, Chung describes the liminal spaces between the love of an adoptive family and the isolation of being the only Asian American child in her town. Chung describes the incredible pain of enduring racist slurs from her peers on the playground, which could not be adequately addressed in a family that considered their love for her to be "colorblind." Through a mix of storytelling and present day reflection, she illustrates how such rhetoric can unintentionally close paths to discussing racism and its corrosive consequences.

All You Can Ever Know opens with a white couple asking Chung about the quality of her adoption, and whether transracial adoption would be a good choice for them. She does not have a neat answer for this, and in so many ways, the memoir that follows is a book-length exploration of how these questions do not have easy answers. The memoir eventually culminates in the story of finally meeting her birth parents, at a time when she was having a daughter of her own. It was the overwhelming experience of "having [her] family expanding in these two very different ways," Chung says over the phone.

I spoke to Chung about finding her birth family, and her hope to see more stories centered around adoptees:

VICE: When did you know you needed to write your story—particularly of being a Korean-American adoptee to white parents?

Nicole Chung: I answer this question differently in a lot of different interviews. In a sense, I’ve told my adoption story so many times. It was a very comforting, familiar tale and I had to tell it a lot, because, of course, looking different from my parents, people would ask me questions. Not just people I knew, but strangers in the grocery store. I had these pat answers that I would reel out every time. It was not exactly comfortable but I was very used to it.

I don’t remember a particular moment where I was like, "yes, this book has to happen.” To me that would have felt a lot like hubris. I never really took it for granted that I would be able to write this. But I knew there was a lot of interest in adoption generally. When I started publishing essays here and there about growing up adopted, and about transracial adoptions, about searching for my birth family, I noticed I’d get questions from people. They had follow ups and more they wanted to know about. It was becoming difficult in a thousand or two thousand word essay to show everything I wanted to show.

How did you choose the anecdotes that went in the memoir? It must be difficult to condense so much of your childhood—perhaps a foundation of your identity—into a single cohesive narrative.

The idea of writing my whole life story was never appealing to me—I always knew this was going to be really focused on growing up adopted in a white family, what that was like, the questions that I had. It was hard to choose, and a lot of things got cut. You don’t need to hear every conversation that I ever I had with my adoptive parents about adoption or every single time a kid called me a racial slur. Getting it once, getting that short powerful scene, is enough. I really was trying to pick crucial scenes and conversations that are illustrative of the larger way I grew up talking about adoption and race, or not talking about it as the case may be.

A lot of times, in the book, a particular childhood memory or conversation with my adoptive parents will be immediately followed with me reconsidering that question while I’m trying to get information about my birth family. Me wondering about my siblings, will be followed by a scene with my sister who was really growing up in ignorance of me. It feels more present and more urgent, which is exactly how it felt in the moment. I wanted the reader to be able to experience those along with me, and also see the moments from my childhood that these questions grew out of.

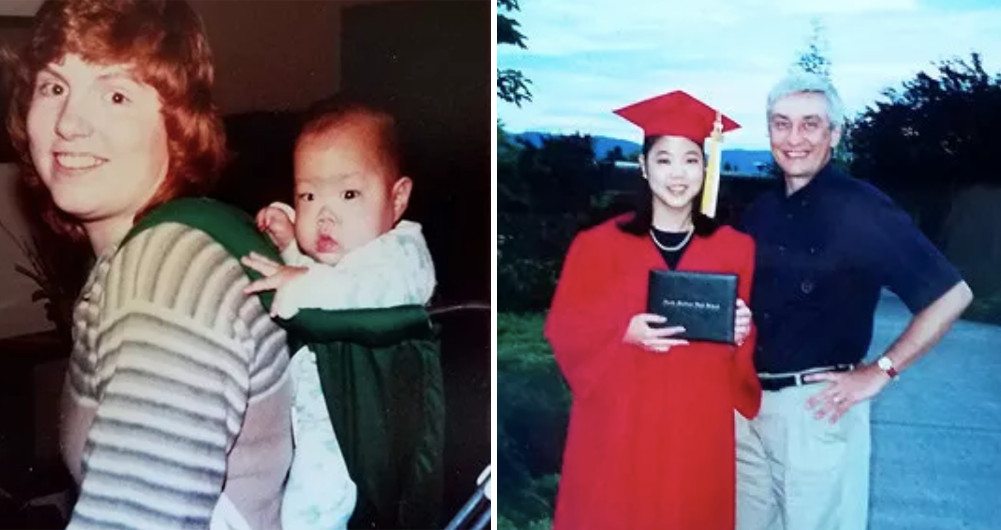

I will say, I think I was helped a lot by the fact that I wasn’t writing this book while I was searching for my birth family. Or while I was pregnant. Those parts in the story happened ten years ago. So I have had space and some time. It doesn’t mean I feel certain things any less strongly. I think I have had some time and perspective to see how things have worked out.

It's a bit wild, the fact that you finally connect with your birth parents at the same time you're having a child of your own.

It’s so fascinating to me that that’s how and when it all happened—these two things happening on parallel tracks. The first time I heard from my birth father was when I was in labor with my daughter. If this were fiction, you’d be like, “that doesn’t seem very realistic.” But it’s real life and that’s how it happened. I was thinking about how it felt to have my family expanding in these two very different ways.

I was really naive about the search and I remember thinking it would go a little faster than it went. I was not expecting to be literally in labor by the time things started happening. I underestimated how much time you spend waiting for, I assume, my number to come up in the queue, so that my intermediary could get my sealed adoption file. I just didn’t know how much time it would take. I was thinking, my second trimester this will all be done—and of course it stretched into my third and happened while I was giving birth. It’s poetic and it was so much to be happening at once.

Were people apprehensive or excited to have their story shared? Did you have to do additional research to supplement your memories?

When I was researching for the first time, I did feel very apprehensive about searching for my birth family. I wasn’t sure what I would find, I wasn’t sure how I would feel. I was very anxious talking to my adopted parents about it. So much of it was a solitary journey. It wasn’t because I didn’t trust people and it wasn’t because I didn’t care what they thought. I felt so strongly at the time that this was a decision I had to be okay with, and I had to make up my own mind, and move forward with what I thought was the best decision.

When I started writing, I already had a lot of pieces of the story, but I did end up interviewing family members to get information. I had heard these stories about my adopted parents, for example, or my sister—I’d heard these stories so often that I knew they were true but wanted to double check before going to print. I was also really fortunate in that I’ve kept a diary for many, many years. At that point in my life, there was a lot happening, and I was writing daily journal entries about the search and about my pregnancy and how all of that felt. I’d get a new piece of information from my birth family or a letter from someone in the family and I’d write that down. I wasn’t thinking I would ever write about it publicly. I think I’d envisioned sharing the journals with my child one day, so she would know the story of her birth and also this reunion.

Were there other writers you turned to, or any other transracial adoption memoirs that inspired you as your worked on putting your own story to paper?

It’s hard because there are so few memoirs by adoptees, or even by Asian American women. But a lot of writers have made an impact on me, even if our voices and styles are nothing alike and we write different genres. Celeste Ng comes to mind. Way before—I don’t know if influenced is the right word, but certainly inspired—Amy Tan was the first Asian American writer I read. And we aren't anything alike. I mean, I was adopted and grew up in a white family. But the idea that an Asian American woman could be a celebrated novelist felt huge to me. They made what I wanted to be seem more possible.

I didn’t get to read a lot of books by Asian American authors as a kid. I really wish I had. I think the reason it took me so long to even think being a writer was a possibility was partly because I didn’t grow up seeing people like me doing it. It's been an incredible year for Asian American women authors, and I don’t take it for granted. I certainly hope that we start to see more, especially memoir and nonfiction by more Asian American women writing in this genre.

It seems like Kristi Yamaguchi was hugely influential to you in that regard—simply for demonstrating that an Asian American woman could achieve success.

It’s so hard for me to talk about her without getting emotional still. Seeing her, when I was growing up, changed a lot of things for me. I didn’t know any other Asian Americans really, not living near any, especially when I was younger and in a smaller, private school environment which was even less diverse than a public school would have been. Just seeing her meant so much. It had never occurred to me that Asian American heroes could exist.

We talk a lot about representation in pop culture and in the media. It can be so important and life-giving to children, especially. I wasn’t thinking about broader political issues of race and prejudice and things like that when I was eight or nine years old, but I was aware that I didn’t know anyone else that looked like me, and I was getting bullied a lot at school for being the only Asian kid. Just seeing someone like me on TV being celebrated—of course that was going to have an impact. Getting to talk to your childhood hero is incredible. It’s wonderful to get to tell somebody how much their work or advocacy meant to you. We don’t do these things in a vacuum. We do these things and there are witnesses.

What are your loftiest hopes with All You Can Ever Know?

It’s meant a lot to hear from some early readers who are effected, who could relate—some are adopted, some are Asian American, some come from complicated families. I hope we see many more stories about adoptees, telling their own stories instead of having them told for us. If this book helps make any more space for those narratives—it’s a narrative that should be complicated and reexamined. I don’t think there’s a real, honest discussion of adoption in race that centers adoptees. This is one small part of that.

This interview has been condensed and edited for clarity.

Sign up for our newsletter to get the best of VICE delivered to your inbox daily.

Follow Nicole Clark on Twitter.