A Supreme Court Expert Explains How We Got Into This Mess

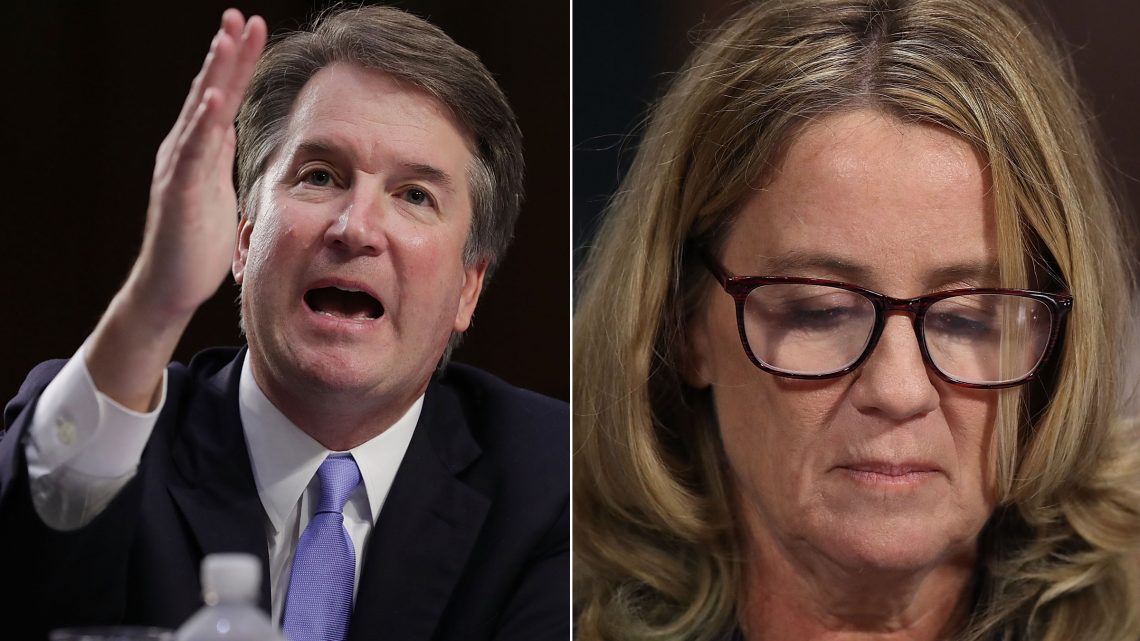

September 28, 2018Supreme Court nominee Brett Kavanaugh has now been accused of sexual misconduct by multiple women, and his confirmation process has been a toxic, partisan fight. The Thursday testimony of his accuser Christine Blasey Ford was reminiscent of the Clarence Thomas hearings, during which Anita Hill said Thomas sexually harassed her, though in that case Thomas was still confirmed. With so much hanging in the balance of the upcoming confirmation vote—including potentially the overturning of Roe v. Wade—it's worth asking how the Supreme Court came to be so steeped in chaos and brinksmanship.

To put the conflict in context, on Thursday morning, before the hearing, I spoke to Christopher Schroeder, a professor of law and public policy at Duke who served in the Office of Legal Policy in the Justice Department, where he supervised the evaluation of Barack Obama’s judicial nominees.

VICE:Were there ever confirmation battles like this? How has the Supreme Court confirmation process changed?

Christopher Schroeder: There have been some protracted battles, but at least in their procedural aspects, not many of them have been similar to this. We've only had hearings that involved nominees since 1939. [Supreme Court Justice Felix] Frankfurter was the first nominee to actually appear before the Judiciary Committee. There weren't many hearings of the committee itself prior to that. [Supreme Court Justice Louis] Brandeis had a classic one when he was nominated in 1916, where the committee heard testimony and then stopped and heard more testimony. That went on for four months but Brandeis never appeared, so it had a different flavor to it. We've actually only had candidates before the committee since 1939.

Was there a particular reason they changed the rules in 1939?

[Frankfurter] was a very visible professor who had a lot of influence in terms of friendships he had on the court and the appellate court, and there was a lot of concern about whether he was going to move the court in a more liberal direction, so they wanted to hear from him personally. He actually refused to answer any questions. He just sat there and said, "I've got a public record. You can read my record." It was the least informative a nominee has ever been. But then having established that precedent, it just evolved in the era going forward that, for the nominees after him, there was a reason to talk them personally. Then we got into Brown v. Board of Education, and the Southern Democrats, in particular, wanted to bring every nominee before the court in order to grill them about what they thought about Brown. By then, we had moved into an era where there was just an expectation that the Senate would do its business more in public.

It was an evolutionary process that was affected by the anxieties over Civil Rights, and the 1960s emphasis on being more skeptical about authority and not wanting to let these kinds of things happen in secret. We've had 32 nominees have been before the committee personally, if memory serves, and we've had 162 nominations. So modern history is a lot different than the pre-World War II history.

When Republicans blocked Merrick Garland's Supreme Court appointment without a hearing, was that the first instance of a justice being denied a seat on the court for political reasons?

You can go back to [Ronald Reagan nominee Robert] Bork for a nomination that was very much focused on what kind of a justice he was going to be, what kind of rulings he was going to make. His judicial philosophy was a big topic of that confirmation dispute. Bork had published a number of academic articles prior to going on the DC circuit in which he had been strongly critical of lots of Supreme Court precedents, and he went so far as to name some of them. He thought the privacy cases before Roe v. Wade were wrong. He thought the Griswold case that said married couples need to have access to contraceptives was unconstitutional because it violated the right to privacy. He was skeptical about the public accommodations provision of the Civil Rights Act that forces hotels and restaurants and barber shops and so on to serve people regardless of race. He thought that violated the owners' freedom of association to make decisions about who they were going to serve.

A lot of hot-button issues at that time came into focus in the hearings. If you went back and looked at the transcripts, that's where a lot of the questioning was directed. His critics said, "He was wrong for the court. He was wrong for the country. We don't want a justice who's going to think that Roe was wrongly decided or that the public accommodations provision is unconstitutional."

Brandeis was criticized just because he was too lefty. He was a progressive justice, and the business interests were opposed to him. So you can go back that far, and find somebody who was really put on the hot seat because of his judicial philosophy. It's been around for a while. It didn't just start with Garland.

With Kavanaugh, he's been caught telling white lies to the committee already. Is that common? Have previous Supreme Court justices even gotten away with the type of lies he's told to the committee?

I don't think there's a comparable nominee that I can think of who has said things where we've got pretty good documentary evidence that he has mis-explained his past—that he was more involved in things than he said he was because emails exist. Clarence Thomas famously said, when asked by a senator, "Have you ever discussed Roe v. Wade with anybody?" that he had never discussed it. Most people think that was false, but there was no way to demonstrate it. You can point to examples in the past where nominees have shaded the truth, or worse, but it seems to me that Kavanaugh has taken that to a new level of whitewashing his past excessively. He's done it up until recently with his personal story, and reacting to these allegations. His opening salvo was basically he claimed he was a choir boy and now he's at least conceited that he engaged in a lot of drinking, but he never sexually assaulted anybody.

How did Republicans blocking Merrick Garland change the confirmation process?

It made the process even nastier, in the sense that you'd have to believe, for instance, if the Senate switched hands in November, the Democrats would feel pretty emboldened just to say, "We're not going to confirm a Trump appointment until after the next presidential election," and they'd cite Merrick Garland as the example [and argue], "If we could wait 400-plus days or whatever it was in that case to fill a seat, we can go with eight justices."

All these instances of political moves to deny one side a seat is a one-way ratchet. Things never get better—the other side repeats the strategy as we go on.

How does that play out? Is it just going to be each party blocking each other infinitely? It seems unsustainable.

I agree with that, and I don't see a dynamic that lifts us out of it because the court has become so important to the most activist wing of each party, and they're the ones pressuring their senators, either to ram people through or to deny the other side the ability to get a seat filled. I don't see any either side sort of unilaterally disarming and saying, "No, we have to go back to the days when it was less political," because their energized base views each of these nine seats as so fundamentally important. I don't know how we get out of it.

I don't see the mechanism that is going to improve things in the near future. We've got to be a larger change in the pot. We have to become less polarized politically across a whole range of issues, and then the court question would settle down some.

It seems like we can't get more polarizing than Trump, but, knock on wood.

Amen.

Sign up for our newsletter to get the best of VICE delivered to your inbox daily.