What Brooklyn Really Looked Like in the 70s and 80s

September 18, 2018Before it was a global brand, Brooklyn was just a place people lived. Lots of them. From Bensonhurst to Park Slope to Bedford-Stuyvesant to Greenpoint, New York City's most populous borough may also have been its most diverse. And there has been no shortage of modern pop-culture homages to the area's rich cultural past, from the films of Spike Lee—himself a rather imperfect critic of gentrification—to the novels of Jonathan Lethem and Jennifer Egan. In recent years, writers like Adelle Waldman and filmmakers like Noah Baumbach have tried to capture both the rapidly-shifting metropolitan landscape (and what that means not just for rent and real estate but also for love and culture) and what it was like to grow up in, say, modern Park Slope before it was the butt of jokes about baby-strollers piloted by yuppies making six figures.

It's in the context of an obscene amount of Brooklyn hype that photographer and South Brooklyn native Larry Racioppo just released his book Brooklyn Before: Photographs, 1971–1983, which includes essays by fabled Village Voice writer Tom Robbins and art critic Julia Van Haaften. VICE caught up with Racioppo to find out why he decided to start taking photos when he was young and roaming the Prospect Park area, what it really means to say Brooklyn was a different place then, and how its interwoven communities have changed—and sometimes refused to change—since his boyhood. Below, in an edited transcript of our conversation, he lays out his thoughts on all of that while detailing the story behind a handful of remarkable photos from the book.

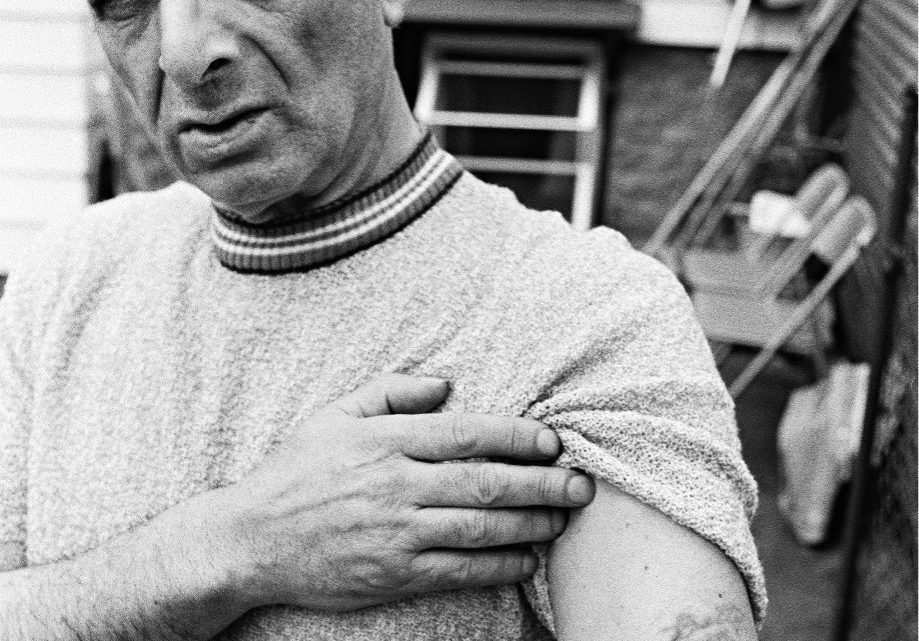

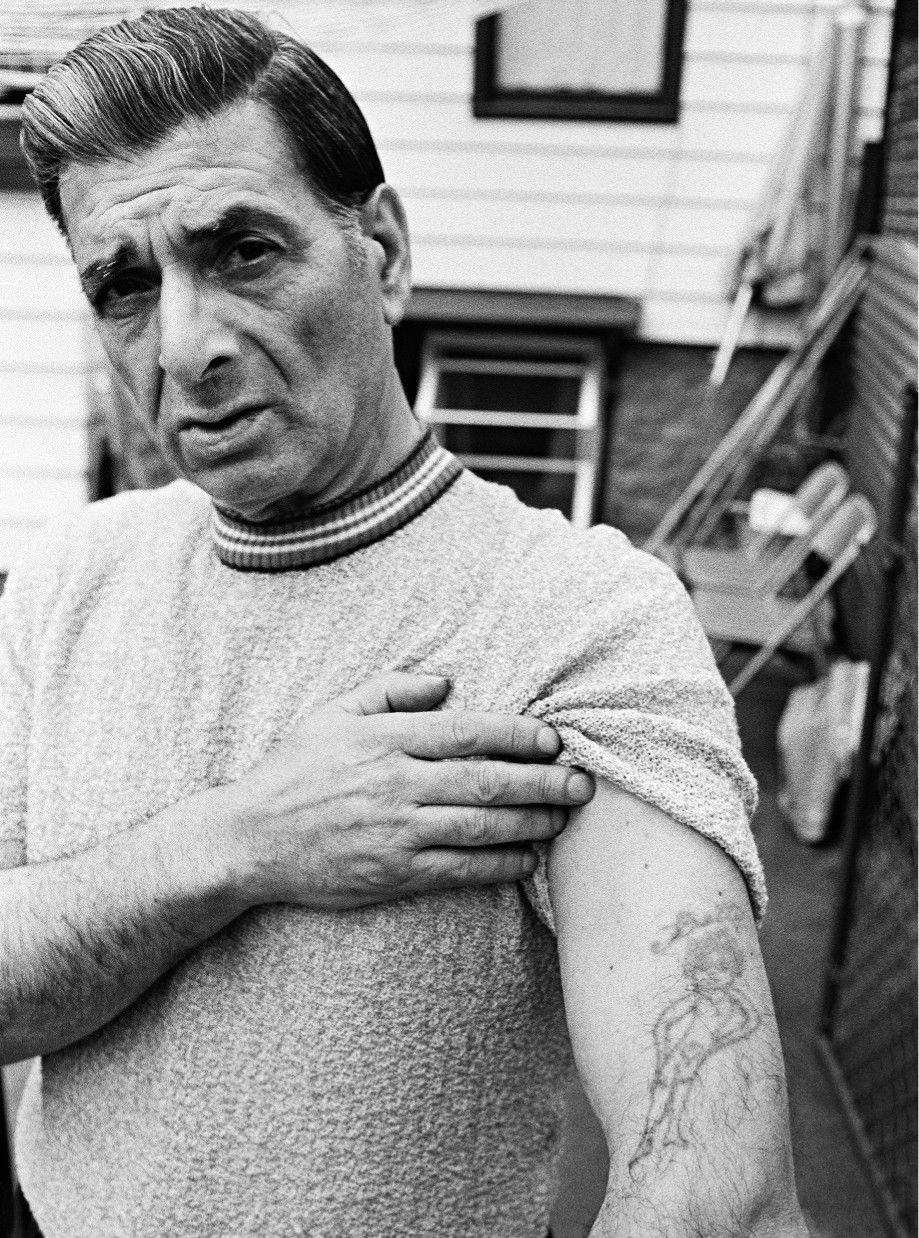

That's one of my uncles. He was in World War II and came back with shell-shock. He never worked again. He lived with my aunt and was very quiet, but every now and then, I would be able to talk to him. I asked him about that tattoo and he showed it to me, said it was [done] at a backyard party. I thought it was very funny, and so simple compared to the extreme art of tattooing now—such a basic World War II tattoo.

A friend of mine had a camera and he lent it to me. I took my first roll of film walking around the city talking to people and I just sort of liked it and it stuck with me. I would walk from probably 2nd or 3rd Street to Greenwood Cemetery to my folks' house in Sunset Park and photograph along the way. I’d meet people and kids. It's pretty much all handheld 35 millimeter black and white film. I never really touched color until many years later.

The work in this book is very specific to the years '71 to '83. I had an inexpensive 35 millimeter camera and I’d been photographing for years. I still think Brooklyn is a great place to live. Tremendous diversity. But except for Park Slope, most neighborhoods aren't very integrated, as you know. I had a really interesting job working for the city, for the housing department, called HPD, and I drove around the city for 20 years photographing it. And I saw almost every neighborhood in the city. And you could see that people got along at work, but when they went home, it was pretty separate.

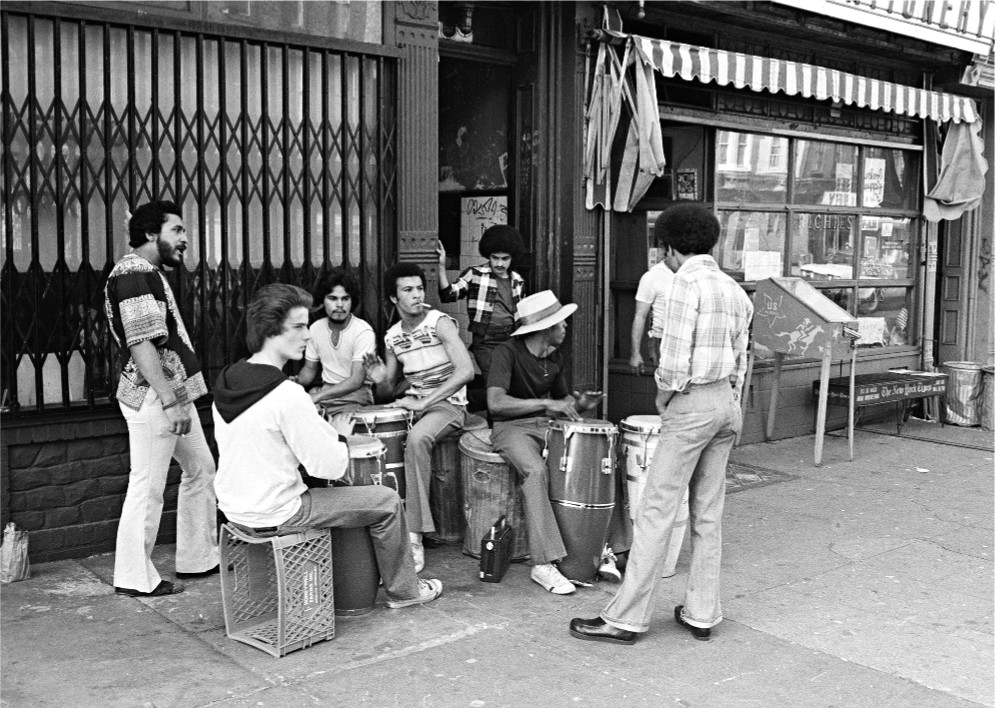

That's around the corner from my house, and it's just a very different place now. Those guys are in front of a liquor store that has that plastic shield from the 70s. Now, it's a fancy, very high-end liquor store. We don’t see people on the street playing like that anymore. It's a much more gentile place. At that time, the Irish were leaving the neighborhood to some extent. The Italians were there and Puerto Ricans were coming in. Now it's like Central-and South-American.

To me, Brooklyn is really about change, and it's about immigrants. If you're not comfortable with change, Brooklyn is a bad place to be. But for the most part, there weren't any really big gang fights. It was nothing major where you felt frightened or really uptight. You saw each other. You worked with each other. But you knew who you were, too. You knew the difference. It was a very working-class neighborhood. It was Irish and Italian and Puerto Rican. And what brought the groups together [in my area] was Catholicism. People knew there was some tension, but nothing really terrible. And people pretty much got along.

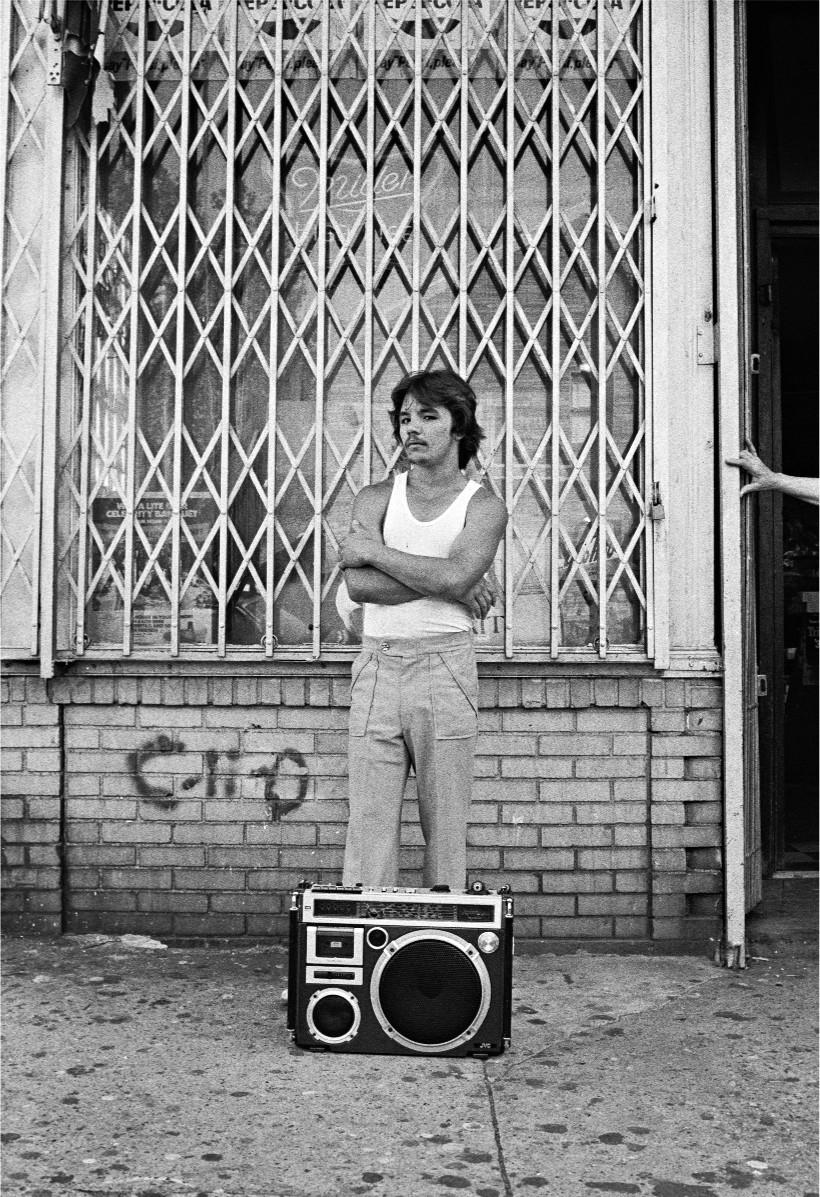

Classic 1980s New York. I've seen loads of boomboxes. His is relatively small—it was part of the change. He was outside an Italian grocery store. The building he's sitting in front of is where my grandmother and two of my aunts lived. Now that store is a Dominican bodega. Eventually, the neighborhood changed from Italian to more Hispanic. I asked the guy if I could take his picture. He said, "Yes," but you see he's wary. He looked like he was uptight about me. He didn't really know what I was up to. Back then, hip hop really wasn't happening there. It was more like a punk scene and rock scene. The people I knew were going to CBGB and the Mudd Club. It got much different later.

Rents were so low, you could work and make a decent living without a college degree. Things were cheap. Most neighborhood guys didn't finish high school. Some didn't finish grammar school. But they made a really nice living and could raise a family. A lot of that isn't really happening anymore. It's just very tough. A lot of people are being pushed out, and there's all these issues about gentrification. It's good for some people, bad for others. Depends on where you are in your life. It's hard now, with the way your rents are in Brooklyn and New York. I rented a small storefront for 35 dollars a month back then. I put a daybed in there and set up a dark room. I was able to buy paper, chemicals, and a few trays and work. I’d take some pictures, process more film, and make more prints.

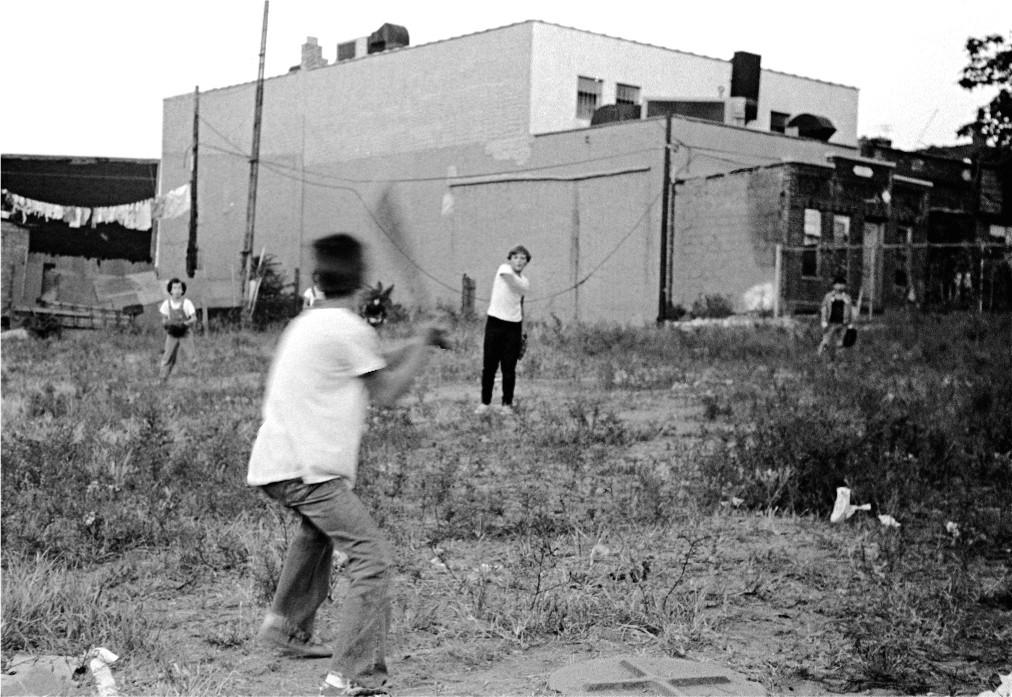

When I was a kid, everything was in the street. Come back from school, go out and play, and your mom would call you when it was dark to go inside. And then the next day, the same thing. On the weekends, we’d go to Prospect Park and play in vacant lots. It's totally changed. We'd be, like, throwing bricks. We'd make these little guns that would shoot pieces of very thick linoleum with a rubber band. You just run around playing all these games—baseball, basketball, and football.

If you played ball, you played ball with everybody. You'd call a play out. The quarterback would say to the receiver, "Run out ten feet and cut between the Caddy and the Chevy.” And the first person who got to that little space would catch the ball because two people could fit. There were all these street games. My grandchildren never play in the street now. They go to the park. They're in organized sports. They have lessons. It's just a very different. Things are more organized. Parents go out with their kids.

In a way it's not as safe as it was. In a way, it's more controlled. But the whole thing with kids on the street is very different.

That was on Christmas Day, on a stoop at my aunt's house. I went to see my aunt and my younger cousin happened to come by. Those were his friends. They went up the stairs of the stoop and I stayed down and pointed up. They surrounded me. It cracks me up.

It’s totally different [now]. The gun culture is terrifying. When I had my job with the city, I actually had to photograph a woman's bible where a bullet came in through the window and just missed her and went into her bible. This was a different time. People didn't have guns.

If there was a fight, the most you might see was a baseball bat. Really, teenagers didn't have guns. There wasn't the level of street crime that there was even ten years later. It has really changed. And now there's a big thing, my more political friends, my PC friends in Park Slope, would never let their kids have a gun. Kids like to play with these things. I see these video games my grandsons play. They are so deadly violent—no more plastic toys in your hand.

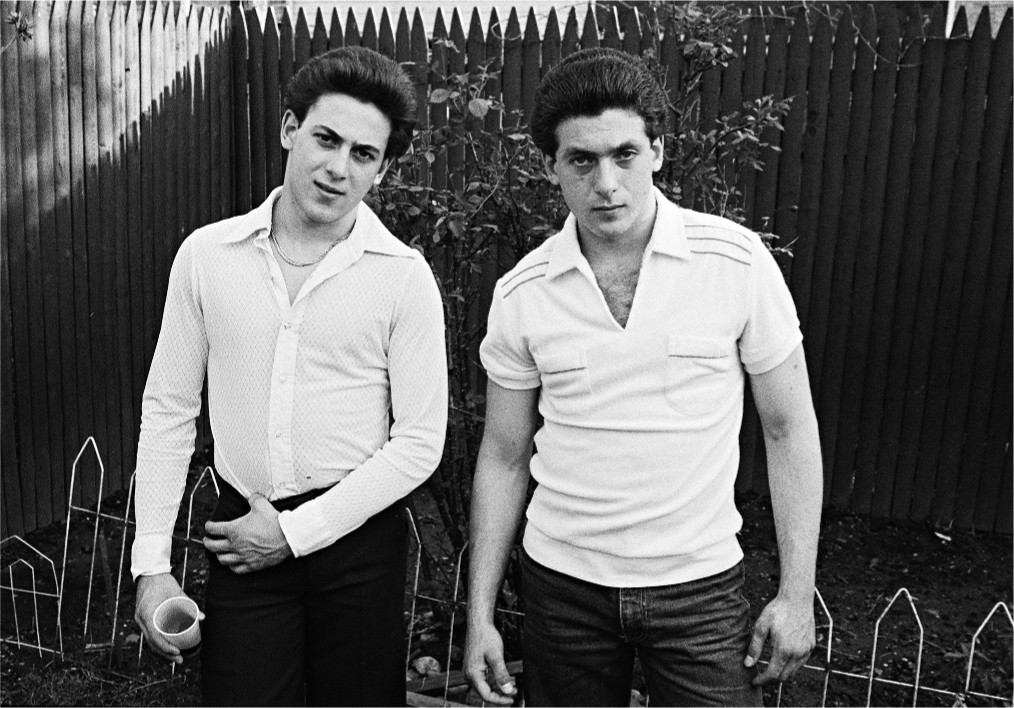

They're two of my younger cousins, and they both had very hard lives. They were handsome boys who were sweet to me, but very tough street kids. That was Brooklyn style, kind of like John Travolta in Saturday Night Fever. It's like a cliché. They were dressing like that period. There are some photographs I have in the book where it would say, "Rock sucks. Disco sucks," written and crossed out on walls in Brooklyn. People who were into the rock didn't like disco and vice versa.

I was living on 10th Street between 7th and 8th [Avenues], and that church was right around the corner. They would play music on Friday and Saturday night. It was the French Haitian Church. It was beautiful. But the kids would be in church for hours. I don't know if you were raised a Catholic, but Catholic mass is like 45 minutes, and in the summer, you cut it down to 15 minutes. But some of those Baptist events I've been to, people were in the church three or four hours and just getting warmed up. So these kids would have to go there all day. When I caught them on a break I always asked if I could take their picture. They lined up like that on their own. They just lined up and stood for the photograph. That area now is so expensive, you could not have a storefront Pentecostal church on 7th Avenue. The rent would be prohibitive.

It's interesting now when I go through Bed-Stuy or Bushwick to see all of the young white kids there. When I was working, you really didn't see any. You would see either Latino or black people. And the neighborhood's really opened up. A big factor back then is that housing was inexpensive. We rented a big loft on 12th Street and 7th Avenue. It was 3,000 square feet and we paid $100 a month. When I first got my own apartment , the rent was $120 a month. My parents thought it was scandalous. They were paying $50. They thought, "How could someone charge 120?" The same apartment would be a thousand or two at the very least today. Having a low rent enabled people to do their art, to do their work.

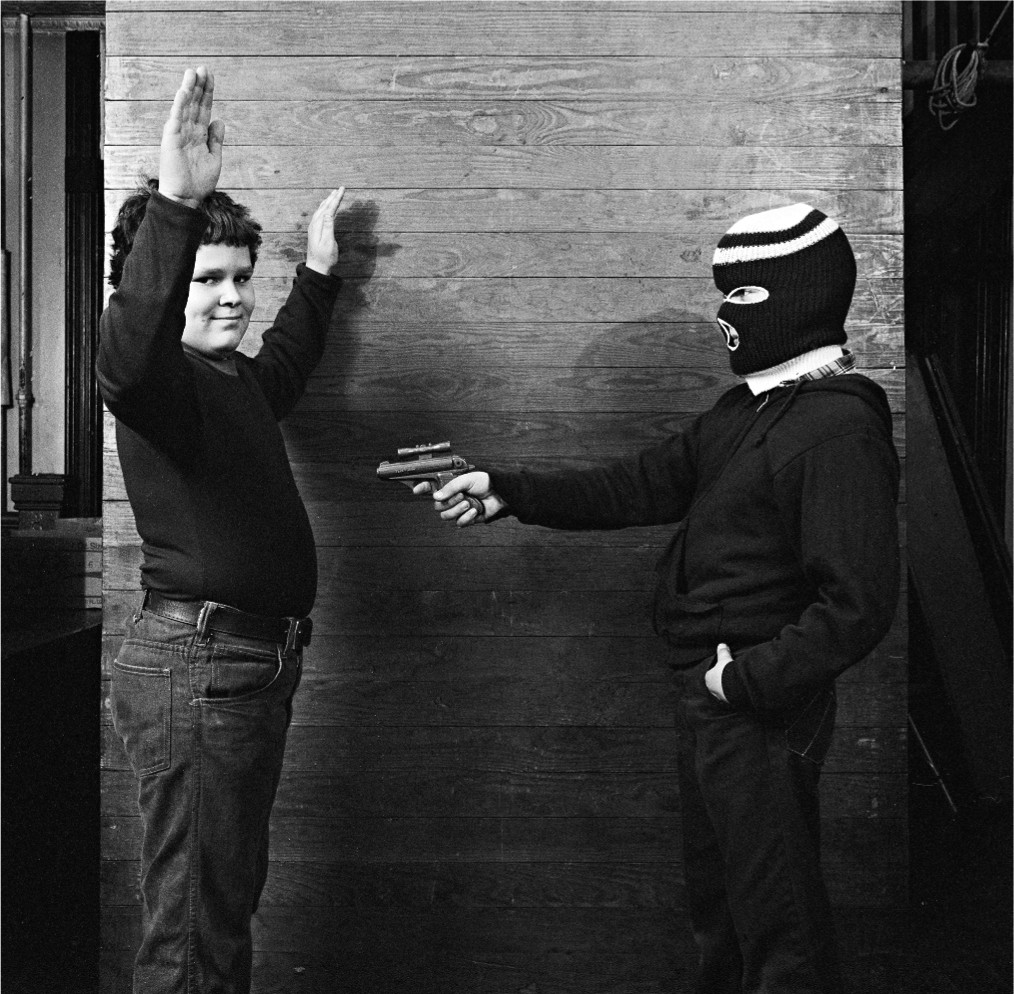

Every Halloween, I'd go out about 3 to 4 PM after school and walk until it got too dark to shoot. I had no flash—just a handheld camera. One year, the local church had a Halloween party and I’d just bought a bigger camera and a flash. I went over there to see if I could get some good pictures. I set up that piece of wood as a background. I was doing like a studio shot. It was the vampire, Batman, and these two kids came up and I said, "What are you?" The kid threw his arms up and said, "I'm a victim." The guy said, "I'm a mugger." He pulled out the plastic gun.

I thought that really summed up the times. People were starting to be aware of the changes. The city was getting tougher and kids would think of that as a costume. I thought that was really amazing.

The kids would be throwing eggs or hit each other with shaving cream. We did all this street stuff and I started photographing kids right outside my house on Halloween about 1973. There was a very famous book called Zen: The Art of Photography that was out at the time, and it became a way to think about the world and about yourself. It may sound strange, but that spiritual part was what I was seeking. Years later, I switched to color film, to a bigger camera, shooting four-by-five and eight-by-ten-inch negatives. But I’ve always been drawn back to my early days of Brooklyn photography.

Sign up for our newsletter to get the best of VICE delivered to your inbox daily. Learn more about Racioppo's book here.