This Is How People Can Actually Afford to Live in the Bay Area

August 21, 2018The Bay Area of Northern California is well on its way to becoming a bewitching hellhole in which it’s actually impossible to eke out a living.

Long a hilly sandbox for wealthy elites to play in, the narrow confines of San Francisco’s 47-square mile peninsula have made it unsteady to the foundation-rocking effects of the world’s tech money. During the Obama years, the exploding professional workforce—often white and male—invaded the city’s hippest, cheapest, and (unsurprisingly) largely-minority areas, pricing out residents who lived there before “the change”—of which the Mission is perhaps the prime example. It was a slow-moving land grab, kind of like The Blob but with Ray-Ban glasses, aided by the financial incentives of landlord-ship and the city’s own policies to lure the money (but, evidently, not the “trickle down”) of Big Tech.

The result? A bizarre metropolis where, in the most extreme cases, public-school teachers have gone homeless and people have rented out literal wooden boxes in friends’ apartments when they weren't paying hefty sums for tiny structures erected in someone's backyard.

After late capitalism’s bomb blew up in San Francisco, its fallout spread across the Bay to neighboring Oakland, Berkeley, and San Jose, inevitably leading to displacement and gentrification for those who didn’t have the wealth to fight back. When people talk of “New Oakland,” some do so in a positive way, where stories of muggings and shootings have been replaced by complaints about backyard fireworks and barbecues by the lake. Others utter the phrase more derisively, talking about some bougie cocktail joint that opened in place of a comfy dive. Either way, few Oaklanders who suffered through the alleged chaos of the old days are still around to enjoy the apparent prosperity of the new ones.

Meanwhile, it’s getting harder and harder to actually live here.

According to a recent study by the National Low-Income Housing Center (NLIHC), to afford rent on a one-bedroom apartment in San Francisco—"fair-market" rate $2,500, actual rent probably way more than that—you'd have to earn at least $99,960 a year. For someone trying to survive on the city's $15-an-hour minimum wage, that would mean working three full-time jobs, or more than 128 hours a week. Across the Bay, according to the same study, the numbers for Alameda County (including Oakland and Berkeley) drop to “only” $74,200 a year—fair-market rate $1,855—or upwards of 107 hours a week working at Oakland's $13.23 minimum wage. This is technically possible, if you're okay with working double shifts every day of the year.

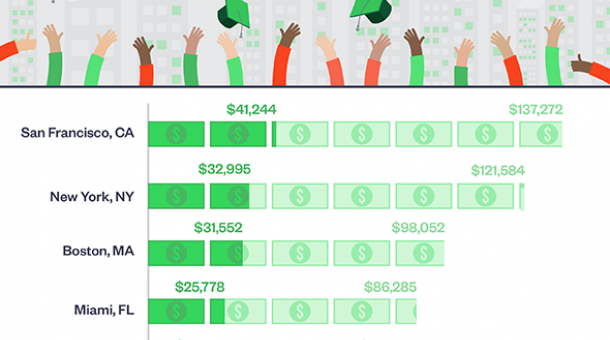

It should be noted that aggregate wealth in the Bay is also different—which is to say much greater—than other parts of the country. Median household income in San Francisco, for example, is around $87,700, while the figure is closer to $55,300 for the country as a whole. According to the US Department of Housing and Urban Development, $117,400 per year is considered "low income" for a family of four living in the San Francisco county. One study recently proclaimed San Francisco's the highest rents on the planet.

"I say it started getting bad in 2014," Azucena Rasilla, a freelance writer in Oakland, told me. "Before, you were okay making $50k. In 2011, you could rent a four-bedroom home in a nice neighborhood [in Oakland] for under $2,000. Now, $2,000 can get you a studio, if that. Anything under $50k only works if you have a partner, and that partner makes around the same. It’s challenging for single folks unless you’re willing to live with hella roommates."

So, how did we get to this untenable situation?

Broadly speaking, the story starts around the late 70s, when there was actually a surplus of homes that were affordable and available to low-income families in the United States. That surplus is long gone. What happened? Well, in part it was that the federal government pulled back from building public- or project-based housing, with the Reagan administration in particular slashing the Housing and Urban Development (HUD) budget by over two thirds. The other big drag was Proposition 13, which California voters passed in 1978 to gut the state's property-tax system, helping inspire so-called "tax revolts" nationwide. The archaic structure left in its wake discourages people from ever giving up their homes and exacerbates income inequality by forcing many into long-term rentals they can't afford.

But the housing crunch has been exacerbated by recent events, some of them unique to California.

The foreclosure crisis that took off in earnest around 2006—California was one of the hardest hit states—jettisoned millions of former homeowners into the rental market, just when millennials were entering it in record numbers (their crippling student loan debts made it impossible to buy). In the Bay Area, the metastasis of the Not In My Backyard—or "NIMBY"—ideology prevented or restricted new housing construction. The best example can be found in Marin, north of San Francisco and one of the country’s wealthiest areas, where development has been successfully stymied ever since the region pulled out of plans to extend the Bay Area Rapid Transit (BART) line in the 1960s. Wherever there is wealth in America, there are rich people who don’t want new neighbors.

It’s been clear for some time what’s needed to solve this problem: more housing, most of it affordable, much of it publicly-funded. But any nationally-proposed solution will run into a wall as long as the great ideological hypocrisy of the Bay Area persists. Meanwhile, the remarkable scourge of homelessness in the region continues to raise eyebrows around the world.

"San Francisco is known for being progressive, but has the most extreme NIMBYism in the country," Diane Yentel, CEO of the Low-Income Housing Center, told me. "I don’t know how you square that."

OK, but let’s say you just have to live here. According to the US Census Bureau, the median income in SF proper is about $87,700 a year, while in Oakland that number dips down to $57,800; given the projected income requirements above, this is a nightmare waiting to happen. Still, people are doing it both at those "average" pay levels and minimum wage, and I wanted to learn how. With the caveat that extremes on both ends of the income scale skew the numbers—the Bay Area's wealth is rightly notorious, and again, homelessness here is out of control—here's how people are (just barely) making it work at both tiers in 2018.

Where Do They Live?

Median Income: Not San Francisco, unless they know somebody or have been there forever. Forget about Berkeley. They might be able to swing Oakland, where it’s a little easier than SF, but only if they break into whisper network of sublets and deals from "good locals" trying to keep the city legit. You can find a room in a house for less than half of the city’s average rent with the right connections.

Sonya Mann, a communications manager based in the East Bay, pays a few hundred dollars below market rate because of a special family deal, splitting a 1.5-bedroom for $1400 a month. "That’s privilege right there," she told me. "We wouldn’t have been able to land this place without me being related to the landlords, because there’s so much competition for open apartments. If we suddenly had to move, we’d probably leave the area."

Minimum Wage: Alameda is somewhat appealing, but also kind of its own thing, both ideologically speaking—as a former naval base, it has some weird Lynchian Americana simmering below the surface—and practically, because of limited public transit. It can take almost an hour to get over the Bay Bridge, but you can take the 20-minute ferry into San Francisco. El Cerrito is a nice option, but by the time you read this, it’ll be gentrified. There are deals to be had at the far edges of the BART system, but depending on any given area resident’s gig, the transportation cost (an extra $6 or so each day for the round trip) may not be worth it.

However, no matter if they’re median income or minimum wage, whatever place they find, people often feel stuck there for good. "Right now, I pay rent from 11 years ago,” said Rachel Wood, a teacher’s assistant who works in restaurants part-time, lives in Inner Richmond, San Francisco, and earns roughly the 40-hour-a-week equivalent of minimum-wage over the course of a year. “It's gone up slightly, but not much. I will be fucked if we get evicted. I will have to leave."

How Do They Get Around?

Median income: This is really about their work situation. Will their boss pay the $6 peak Bay Bridge toll? Cool. Do they go into work early enough to get a spot and/or can they afford the $25 or so a day to park in a San Francisco garage during work hours? Very cool, though that means they might be inclined to want to jump off the Bay Bridge during rush-hour gridlock. Some might make do with a beater car for $2k on Craigslist. Others try to get their boss to pay for their Clipper Card: If you need BART and SF-based MUNI rail, that’s $94 a month; if you need to get around on the East Bay AC Transit system, it’s $84.60. (One secret to keep in mind is that AC Transit bus drivers don’t necessarily give a shit if you pay or not.)

“I have a car. It’s a 2001 Toyota Corolla, so it’s maybe worth $3,000?” Mann told me. “I use that in the East Bay, but I also ride BART a lot. I refuse to drive in SF, so there it’s mostly BART and I fill in the gaps with Lyft.”

Minimum Wage: Locals in this income bracket I know might find a used bike for, say, $100 they can ride around town. (There’s a bus you can bring your bike onto that crosses the Bay a few times a day; it costs $1 a ride.) BART is often too expensive for their budget; MUNI will cost $2.50 for a single ride through SF, while AC Transit runs $2.35 a ride through Oakland. All of that is to say that traveling around the Bay, like just about every American city, is impossible without some kind of financial sacrifice. (This is a good place to note that BART stops running around midnight, even on the weekends.)

What Do They Eat?

Median income: These folks may be able to afford Whole Foods or weekly farmers' market trips if they trim from other areas in their life. If not, they might consider an alternative like an “imperfect produce” box for $20-$40 a week, depending on their haul. They can eat out maybe once a week, but probably only two dollar-signs on Yelp. Maybe a three-dollar-sign for a special occasion like getting a huge promotion. Burritos are their friend.

Minimum Wage: The move here is often to locate the nearest Grocery Outlet (“Gross Out”) and go nuts. At the Oakland location, shoppers enjoy the swinging sounds of 50s R&B and soul as they browse the aisles and even peek at the organics section. Or maybe their low-wage job is in food-service, in which case they can snatch those leftovers.

“When people ask me what my favorite restaurant is, I laugh, because if I'm going out to eat, I'm getting budget tacos or budget Indian food," Wood told me.

How Do They Afford Self Care?

Regardless of income, my line on this is that if you spend money on a gym membership—which some people of less than-enormous income obviously do—you're making a silly mistake. I always tell people to run around Lake Merritt and work out at one of the free outdoor gym thingies, or, better yet, go on a damn hike in the hills.

When people get sick of nature, Mike Davie, a marketing manager from Oakland, noted, they sometimes try urban explorations through the East Bay’s tunnels or the region’s abandoned buildings. “Do research, be vigilant, and watch your step,” he said.

Can They Have Fun?

Median Income: With the mass of performers who live in New York and LA, prices to see weeknight shows are sometimes at least relatively affordable. Not so in the Bay, where—at least in my own experience—shows are often part of some grand tour. People in this income bracket might be able to see decent comedy for about $15, and concerts by bands they actually know for more like $25. The big acts obviously cost more. If they don’t have a MoviePass or the service has collapsed, nights out at the cinema set them back $13-$15 a ticket or more, though some might try taking a night class to snag a student ID that'll trim that some. Bar beers, as they do in most cities, run about $5-7, cocktails closer to $12, and tiki drinks as much as $15. Many Bay Area residents may never see a Warriors game unless they have a CEO buddy, but can get a second-hand Giants ticket when they’re having a bad season.

“[My fiance and I] eat out like twice a week, but our taste in restaurants is mostly low-brow, and that includes fast food,” Mann said. “We both like to party, so alcohol and weed are probably our most expensive recreational habits, followed closely by books.”

Minimum Wage: A common local move here is to meld your way into artist warehouse shows that cost donations at the door. SF Free Cheap is a decent online guide to free days or cheap shows, but there’s also a lot of dumb shit in there to comb through. Some area theaters have $5 nights, usually on Tuesdays, but you have to be sure to get there early. A bunch of weekend dance nights have free entry before 10 PM, so people breeze in around 9:55. At this income level, you might have to forget about the Giants and take BART to the Oakland Coliseum for an A’s game. Nosebleed seats can be had for cheap, and people are known to just sneak down closer to the field after the third inning or so.

Despite how insanely inaccessible it is to new residents of remotely modest income, the Bay really is a magical place, with some of America’s most beautiful landscapes and, I would argue, its most wonderful people. If you can get past the insane array of obstacles wrought by decades of stymied housing construction, the unrelenting influx of new tech money, and good, old-fashioned gentrification, you’ll find no shortage of excitement as you bear witness to the super-rich eradicating a region’s fabric while those left behind white-knuckle grip onto whatever they can.

Hell, maybe you’ll even befriend a few of the rich techies. Why not? That could come in handy, in fact. Because when the next generation of Musks and Zuckerbergs inevitably shut down the city completely to those without unreal wealth, they might be willing to add your name to the "okay poor" list.

Maybe.

Sign up for our newsletter to get the best of VICE delivered to your inbox daily.

Follow Rick Paulas on Twitter.