A Photographer Recreates His Family’s Lost History

July 27, 2018When Chad Hilliard was 11 years old, he took a family trip to Disney World in Orlando. On the last night of their trip, they went to a parade. His aunt, who had just gotten the first iPhone, asked him to take some pictures.

“I was taking pictures of these fireworks and everyone kept commenting on how great and how beautiful the pictures looked,” Hilliard recalled to me at a coffee shop in Long Island City, New York. “I loved the praise and was excited that I had found something that I was good at.” It wasn’t until later that Hilliard realized his family’s enthusiasm was over the quality of the iPhone camera and not his prodigal photographic skills.

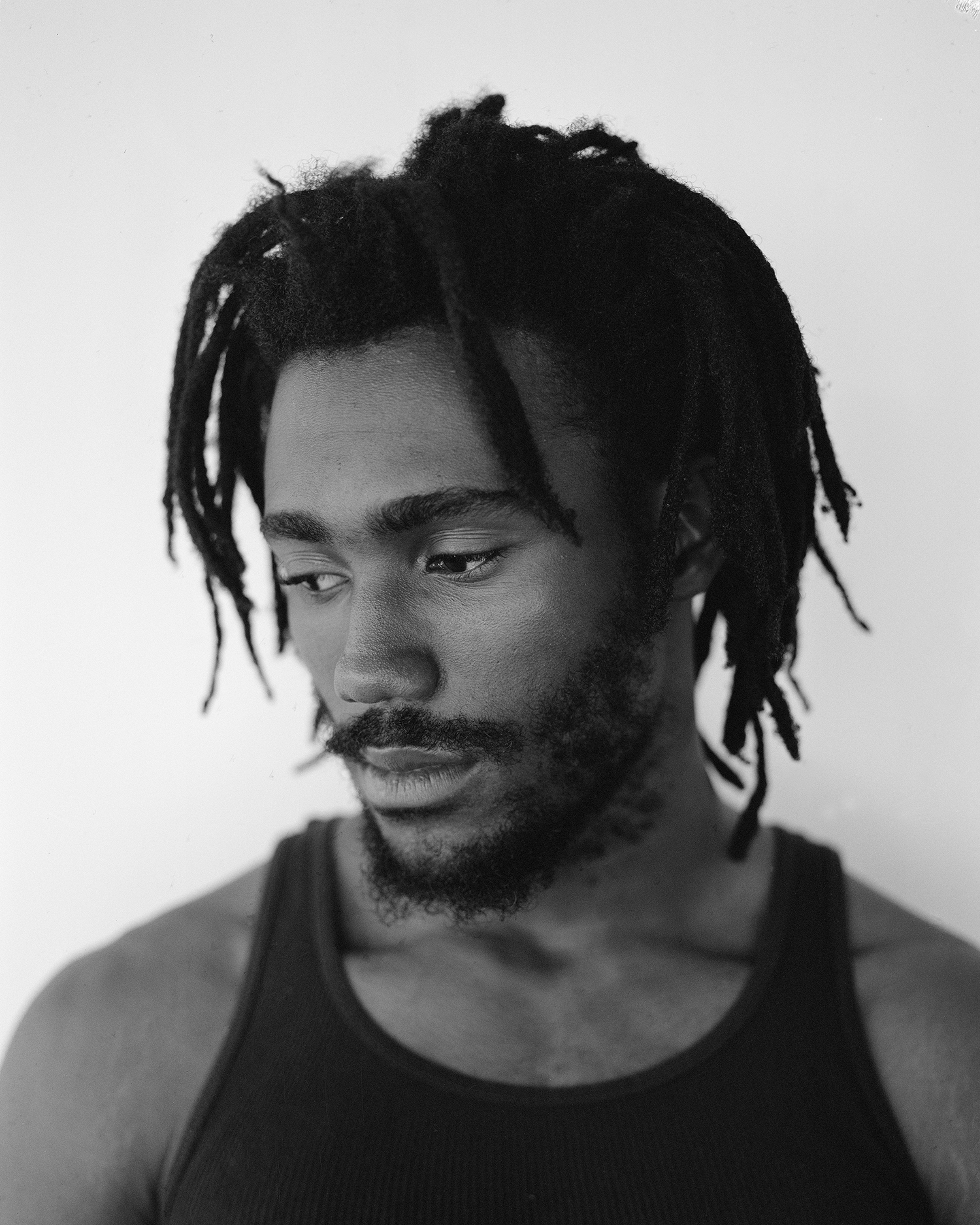

Despite the fact that Hilliard’s initial success with photography might have been a misunderstanding, he has certainly proved himself as a promising and talented young shooter. Hilliard just received his undergraduate degree in both Photography and Ethnicity, Race, and Migration from Yale University. He has incorporated both fields of study to develop a project that uses photos to give a visual narrative to the stories of his family.

“Given the nature of African-American history, having family rooted in the slave trade meant that there wasn’t a lot of documentation,” Hilliard explained. “I wanted to use my camera to fill in the blanks of my family’s lineage.”

When he first started the project, Hilliard would cast actors and friends to play the role of his family. However, the idea of asking someone to inhabit his own narrative when they had their own family and their own life story did not feel genuine. So Hilliard quickly decided that it made the most sense for him and his family to portray his ancestors in his photos. That meant, in addition to photographing his loved ones, he'd position himself in front of the camera and use costumes to represent different roles that his ancestors played—carpenters, engineers, prisoners, and slaves.

“Making these photographs helped me better understand what it was like to be them back then,” Hilliard said.

Despite the deeply personal nature of his work, Hilliard hopes that images connect people together and force them to consider their own family history.

“I think that a misconception that people might have is that this work is strictly about race or strictly about American history," Hilliard said. “I happen to be making work that centers around the African-American experience because that is my own lived experience. However, I don’t want that reality to deter others from considering their own family when they look at my work. My work is created for people like me, but that doesn’t mean it doesn't want to engage with those who are different from me.”

In addition to Hilliard’s active effort to engage a wide audience, he hopes that his work expands the narrative of both the history of African-American men and racial concepts in America.

“It’s important for people to be aware that family and heritage are forms of privilege. And it’s important that those who don’t have such a privilege are not being shamed. [Instead, they should be] encouraged to seek out the missing pieces that make them feel whole,” Hilliard explained.

Such inclusivity and awareness is evident in Hilliard’s approach to his photographic process as well. Primarily shooting large format 4x5 pictures, he tries to make each shoot as collaborative as possible.

“I’m not huge on authorship,” Hilliard confessed. “Initially, I come in with an idea of the type of picture I want to take and try to set things up to execute that vision as much as I can. Once I’ve taken my first shot, I’ll leave it up to whoever I’m photographing to make their own picture. I show them how to use the camera, and then let them position themselves as they wish. Sometimes they choose to photograph me instead. For the third picture, we combine forces to figure out what we liked about the first two, or do something completely different. I like the idea of performing the act of photographing on them, and then letting them do that back to me. By the time we get to the third picture, we feel equally that we’re both authors of some type of work.”

Follow Clara Mokri on Instagram. To see more of Chad Hilliard's work, click here.