The Next Flint Water Nightmare Could Be Closer Than You Think

July 11, 2018Detroit journalist Anna Clark has been covering the region's water problems since 2014, and has been following the Flint crisis since problems with the water there were first revealed in 2015, months after the city switched water sources. Flint went on to become a viral national news story about the failure of government to guarantee clean water in a city of mostly African American residents, then largely fell off many people’s radars as other outrages crowded it out.

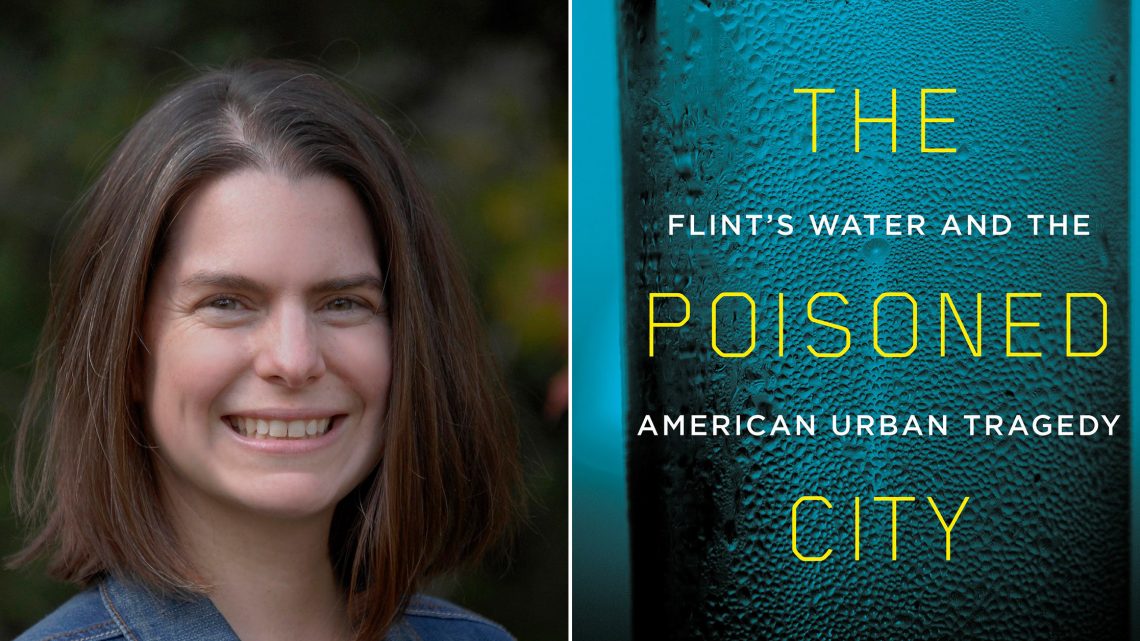

Clark’s new book, The Poisoned City: Flint's Water and the American Urban Tragedy, out this week, retells the story of Flint in a compelling, nuanced fashion that’s sure to make readers angry all over again. It’s a story of failure and misconduct that seems all the more urgent at a time when the people in charge of the government are trying to dismantle federal agencies.

I recently talked to Clark why citizen complaints about Flint’s water were ignored, how media pressure turned the crisis into a national conversation, and whether other cities could be at risk for a Flint-like crisis.

VICE: What made you want to write a book about the crisis and what new info have you uncovered?

Anna Clark: It has a lot of intersecting pieces to it and a story that goes back decades, even before the actual water switch. To really go in-depth with that with a book was a wonderful opportunity to sit with it, think about it, absorb it, learn, listen, give myself a little bit more time to be patient, and try to absorb the complexities of what was happening here. But I also [wanted] to communicate the warmth of the city. It’s a place worth fighting for. I love articles, [but] you really need to get some perspective and put all the pieces together. Little dispatches aren't enough to really communicate what's going on here.

If the media didn’t expose what was going on, do you think the Michigan government and federal officials would have ever done anything?

The spotlight on both local and national media was absolutely essential to this crisis. Stories that happened after the water switch and even before the water switch, including the New York Times, were kind of one-offs. The state said it's fine and journalists were like, What do you do with that? In October 2015, they acknowledged that the water was not safe to drink and connected to Detroit water—not a permanent solution, but essential. By January 2016 this really exploded and became the #FlintWaterCrisis and the full force of emergency intervention and statewide resources began to become available to Flint. Bottled water and filters [were] distributed, so people could have safe water. It makes me sad because if there were more journalists on the ground locally and nationally, things might have changed sooner.

What does it say about our government agencies when they willingly turn a blind eye to health and safety hazards in regards to the poor and people of color?

What happened in Flint is how disempowered and dismissed these people were in the decisions that were effecting their own lives. After the water switch happened, not only were people using whatever means were available to them to register their unhappiness with this strange water that was coming out of their taps, it was also recorded in the local media, but it wasn't enough. The people who had [the] power to do something about it did not take these folks seriously.

This community also didn't have political power because of the emergency management system—they really had no voice at all. The emergency management system in Michigan, which sends in a state-appointed manager to take over the running of a local government that is financially challenged, is disproportionately happening in communities of color, and it’s not a coincidence. This is a terrible lesson we learn again and again. We have this legacy of segregation in our history. This didn't happen by accident. This happened by policy.

What’s happened to the officials who passed the buck as the lead-laced water killed 12 people?

There are 15 people who have been criminally charged so far. Four of them have since had plea deals. The majority of them are people who work with the Michigan Department of Environmental Quality or the Department of Health and Human Services. A few worked with the city. Two of the emergency managers have been indicted. The cases are at the tail end of their preliminary exams and [we’ll know] whether or not they’ll proceed to trial soon. Only one person was fired. Some of the people who are in charge are suspended as these proceedings play out.

Two—including the director of Michigan’s Health and Human Services—are still in their jobs actively working even as these cases play out, which puts them in the curious position of both facing very serious charges, like involuntary manslaughter, even as they are leading the agency tasked with managing the recovery efforts in Flint. There's a special prosecutor leading the investigation because the attorney general's office is constitutionally obliged to represent the state's interest. The state is effectively funding both the prosecution and the defense of these cases, as well as the salaries and all these lawyers. It's insane.

What did independent studies show caused the whole water crisis?

They're not filtering the water properly. They're not adding the corrosion control to the water. Water passes through these aging lead lines and the lead starts disintegrating into the water and then people drink it. The orange color, the discoloration, that was iron corroding into the pipes. It's rust, basically. There was a number of contamination issues, most seriously an outbreak of legionnaires' disease, which is what actually killed people.

Are there more Flints in our future?

We have lead pipes and lead plumbing infrastructures everywhere. Chicago's actually the city that has more lead pipes than anywhere else. This is not OK. Lead is toxic, any amount of lead. We shouldn't be drinking our water out of it. Even the way the federal rules are written, the minimum standards they set essentially allow some lead in the water. I don't think we should be surprised when people are ingesting lead and getting lead in their bodies. This is true even in wealthier and whiter communities. Nobody's immune. Flint should be a wake-up call for folks to take a hard look at their drinking systems, where their water comes from, and what it's passing through. Really raise up a movement to get rid of it, because pretending it's not there is not going to work.

"I think when stories like Flint happen, and they will continue to happen, we really need to recommit to the ideals of the public good."

As Donald Trump continues to roll back regulations and makes it easier for corporations to do as they please, how do you think our failing infrastructures will fair?

It's funny that you mention that with Trump in particular, because infrastructure's supposed to be his thing, right? He's like, I build things and every week's going to be Infrastructure Week. Yet pairing that with the environmental regulations and the way the EPA's been reorganized, there's a real dissonance there. We need good infrastructure to have healthy environments. Healthy environments help serve our infrastructure for the long term. The way that environmental racism works, where some groups of people experience disproportionate harm, is morally wrong.

I think when stories like Flint happen, and they will continue to happen, we really need to recommit to the ideals of the public good. Some things, like making sure that everybody has affordable drinking water, are just the right thing to do. We can't take for granted that things are going to work out toward the public good. I think that what happened in Flint shows that [even though things] were clearly wrong, they were not actually illegal. That should give us an opportunity to think about what kind of structures we can create that serve a more just and healthy world.

This interview has been edited and condensed.

Sign up for our newsletter to get the best of VICE delivered to your inbox daily.

Follow Seth Ferranti on Twitter.